At the beginning of 2011 we started a wide-ranging conversation with Google Creative Lab, discussing near-future experiences of Google and its products.

We’ve already discussed our collaboration on “Lamps”, the conceptual R&D around computer vision in a separate post.

They had already in mind another brief before approaching us, to create a physical product encapsulating Google voice/video chat services.

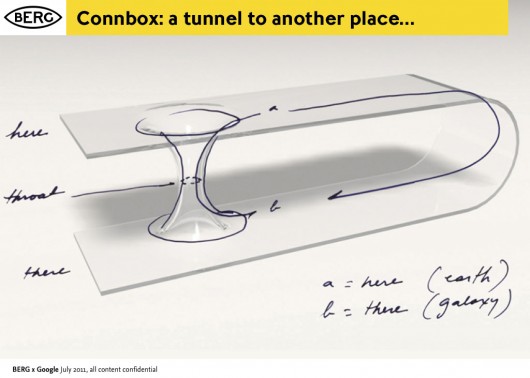

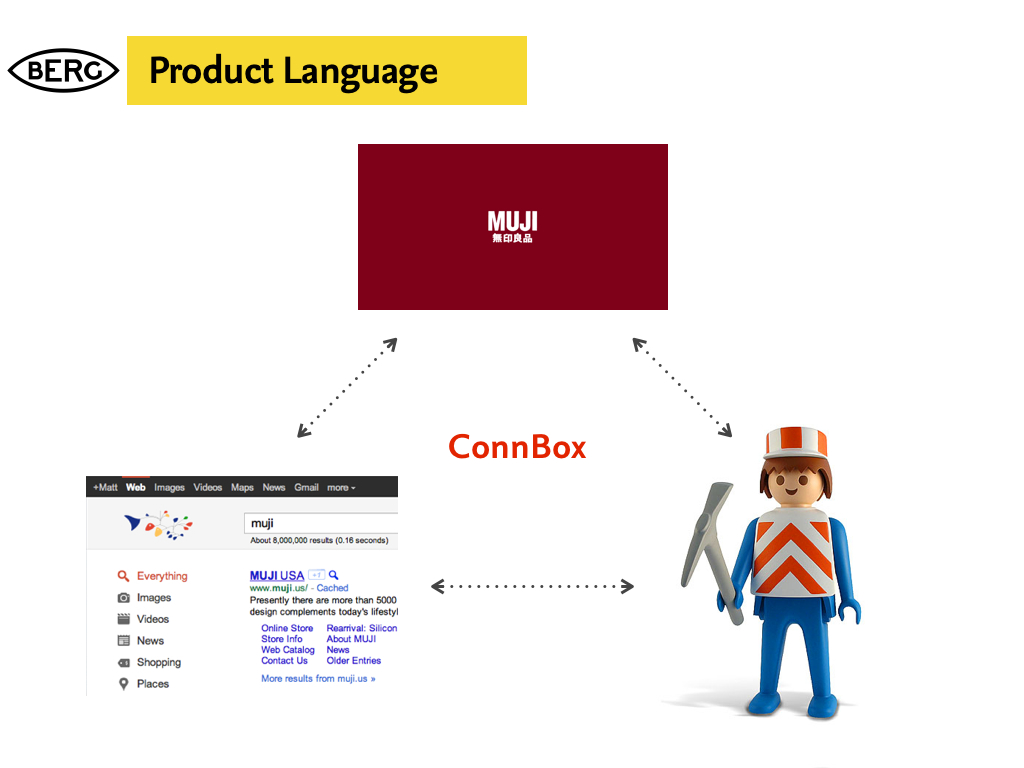

This brief became known as ‘Connection Box’ or ‘Connbox’ for short…

For six months through the spring and summer of 2011, a multidisciplinary team at BERG developed the brief based on research, strategic thinking, hardware and software prototyping into believable technical and experiential proof of a product that could be taken to market.

It’s a very different set of outcomes from Lamps, and a different approach – although still rooted in material exploration, it’s much more centred around rapid product prototyping to really understand what the experience of physical device, service and interface could be.

As with our Lamps post, I’ve broken up this long report of what was a very involving project for the entire studio.

- The Connbox Backstory

- Unpacking the brief

- Material Exploration

- Prototyping: Technical and Experiential

- Proto #1: Polar Bear

- Proto #2: Domino

- Product/industrial design development

- Proto #3: Testing the experience and the UI

- Connbox: Film

- The importance of legible products

- Conclusion: What might have been next?

- Then and now – how technology has moved on, and where we’d start now

- Notable Precedents

The Connbox backstory

The videophone has an unusually long cultural legacy.

It has been a very common feature of science fiction all the way back to the 1920s. As part of our ‘warm-up’ for the project, Joe put together a super-cut of all of the instances he could recollect from film and tv…

Videophones in film from BERG on Vimeo.

The video call is still often talked about as the next big thing in mobile phones (Apple used FaceTime as a central part of their iphone marketing, while Microsoft bought Skype to bolster their tablet and phone strategy). But somehow video calling has been stuck in the ‘trough of disillusionment’ for decades. Furthermore, the videophone as a standalone product that we might buy in a shop has never become a commercial reality.

On the other hand, we can say that video calls have recently become common, but in a very specific context. That is, people talking to laptops – constrained by the world as seen from webcam and a laptop screen.

This kind of video calling has become synonymous with pre-arranged meetings, or pre-arranged high-bandwidth calls. It is very rarely about a quick question or hello, or a spontaneous connection, or an always-on presence between two spaces.

Unpacking the brief

The team at Google Creative Lab framed a high-level prototyping brief for us.

The company has a deep-seated interest in video-based communication, and of course, during the project both Google Hangouts and Google Plus were launched.

The brief placed a strong emphasis on working prototypes and live end-to-end demos. They wanted to, in the parlance of Google, “dogfood” the devices, to see how they felt in everyday use themselves.

I asked Jack to recall his reaction to the brief:

The domain of video conferencing products is staid and unfashionable.

Although video phones have lived large in the public imagination, no company has made a hardware product stick in the way that audio devices have. There’s something weirdly broken about taking behaviours associated with a phone: synchronous talking, ringing or alerts when one person wants another’s attention, hanging up and picking up etc.

Given the glamour and appetite for the idea, I felt that somewhere between presence and video a device type could emerge which supported a more successful and appealing set of behaviours appropriate to the form.

The real value in the work was likely to emerge in what vehicle designers call the ‘third read’. The idea of product having a ‘first, second and third read’ comes up a lot in the studio. We’ve inherited it by osmosis from product designer friends, but an excerpt from the best summation of it we can find on the web follows:

The concept of First, Second, Third Read which comes from the BMW Group automotive heritage in terms of understanding Proportion, Surface, and Detail.

The First Read is about the gesture and character of the product. It is the first impression.

Looking closer, there is the Second Read in which surface detail and specific touchpoints of interaction with the product confirm impressions and set up expectations.

The Third Read is about living with the product over time—using it and having it meet expectations…

So we’re not beginning with how the product looks or where it fits in a retail landscape, but designing from the inside out.

We start by understanding presence through devices and what video can offer, build out the behaviours, and then identify forms and hardware which support that.

To test and iterate this detail we needed to make everything, so that we can live with and see the behaviours happen in the world.

Material Exploration

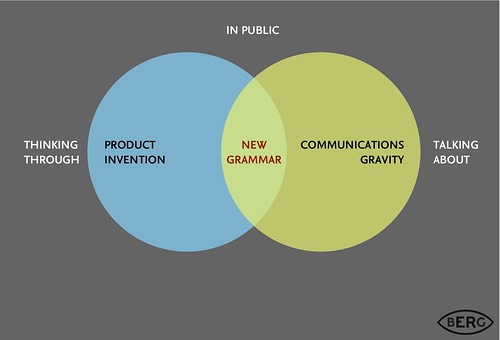

We use the term ‘material exploration’ to describe our early experimental work. This is an in-depth exploration of the subject by exploring the properties, both inate and emergent of the materials at hand. We’ve talked about it previously here and here.

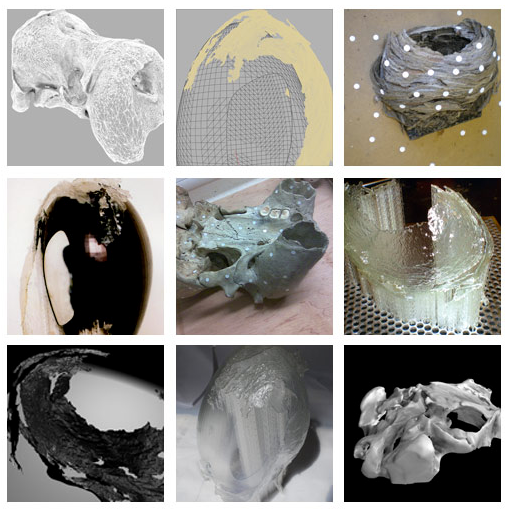

What are the materials that make up video? They are more traditional components and aspects of film such as lenses, screens, projectors, field-of-view as well as newer opportunities in the domains of facial recognition and computer vision.

Some of our early experiments looked at field-of-view – how could we start to understand where an always-on camera could see into our personal environment?

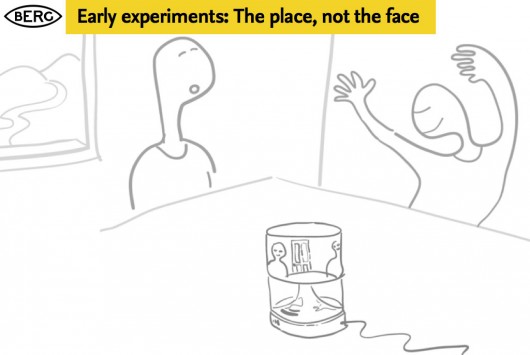

We also challenged the prevalent forms of video communication – which generally are optimised for tight shots of people’s faces. What if we used panoramic lenses and projection to represent places and spaces instead?

In the course of these experiments we used a piece of OpenFrameworks code developed by Golan Levin. Thanks Golan!

We also experimented with the visual, graphic representation of yourself and other people, we are used to the ‘picture in picture’ mode of video conferencing, where we see the other party, but have an image of ourselves superimposed in a small window.

We experimented with breaking out the representation of yourself into a separate screen, so you could play with your own image, and position the camera for optimal or alternative viewpoints, or to actually look ‘through’ the camera to maintain eye contact, while still being able to look at the other person.

One of the main advantages of this – aside from obviously being able to direct a camera at things of interest to the other party – was to remove the awkwardness of the picture-in-picture approach to showing yourself superimposed on the stream of the person you are communicating with…

There were interaction & product design challenges in making a simpler, self-contained video chat appliance, amplified by the problem of taking the things we take for granted on the desktop or touchscreen: things like the standard UI, windowing, inputs and outputs, that all had to be re-imagined as physical controls.

This is not a simple translation between a software and hardware behaviour, it’s more than just turning software controls into physical switches or levers.

It involves choosing what to discard, what to keep and what to emphasise.

Should the product allow ‘ringing’ or ‘knocking’ to kickstart a conversation, or should it rely on other audio or visual cues? How do we encourage always-on, ambient, background presence with the possibility of spontaneous conversations and ad-hoc, playful exchanges? Existing ‘video calling’ UI is not set up to encourage this, so what is the new model of the interaction?

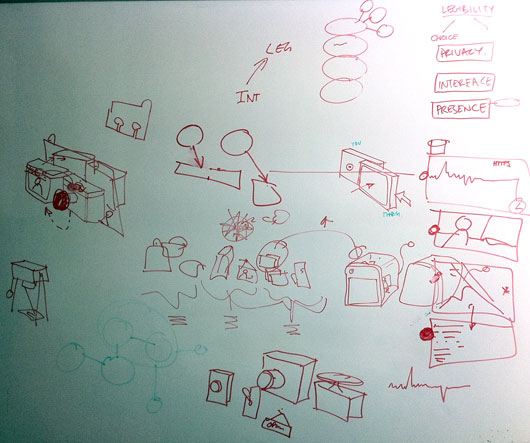

To do this we explored in abstract some of the product behaviours around communicating through video and audio.

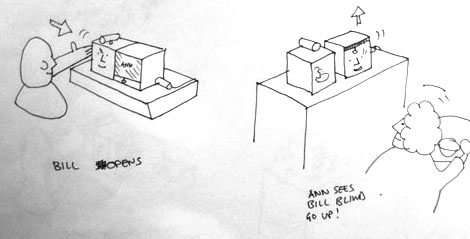

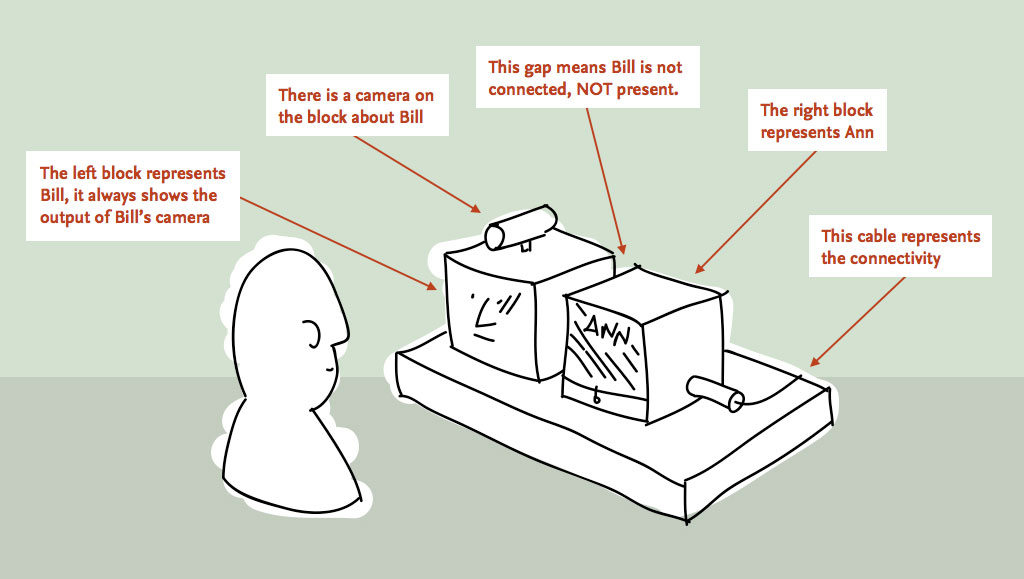

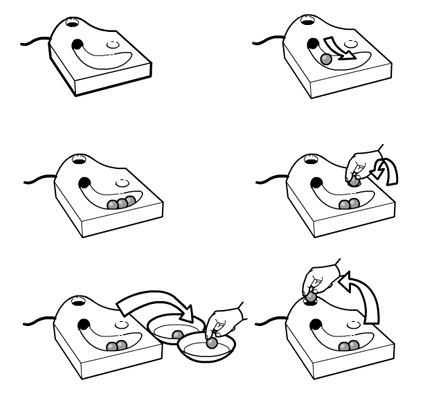

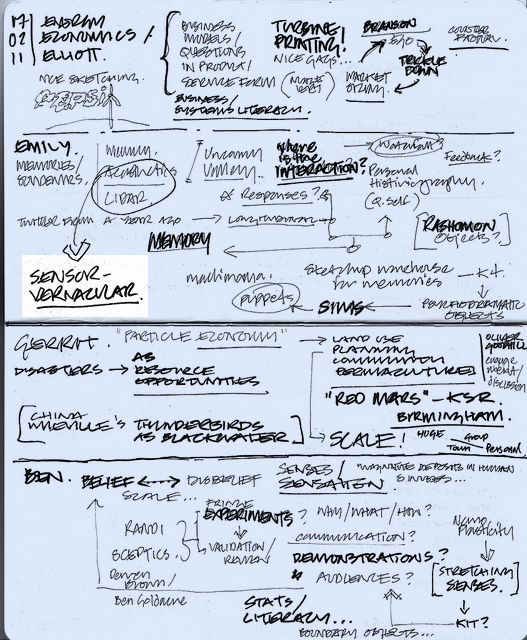

We began working with Durrell Bishop from LuckyBite at this stage, and he developed scenarios drawn as simple cartoons which became very influential starting points for the prototyping projects.

The cartoons feature two prospective users of an always-on video communication product – Bill and Ann…

This single panel from a larger scenario shows the moment Bill opens up a connection (effectively ‘going online’) and Ann sees this change reflected as a blind going up on Bill’s side of her Connbox.

Prototyping

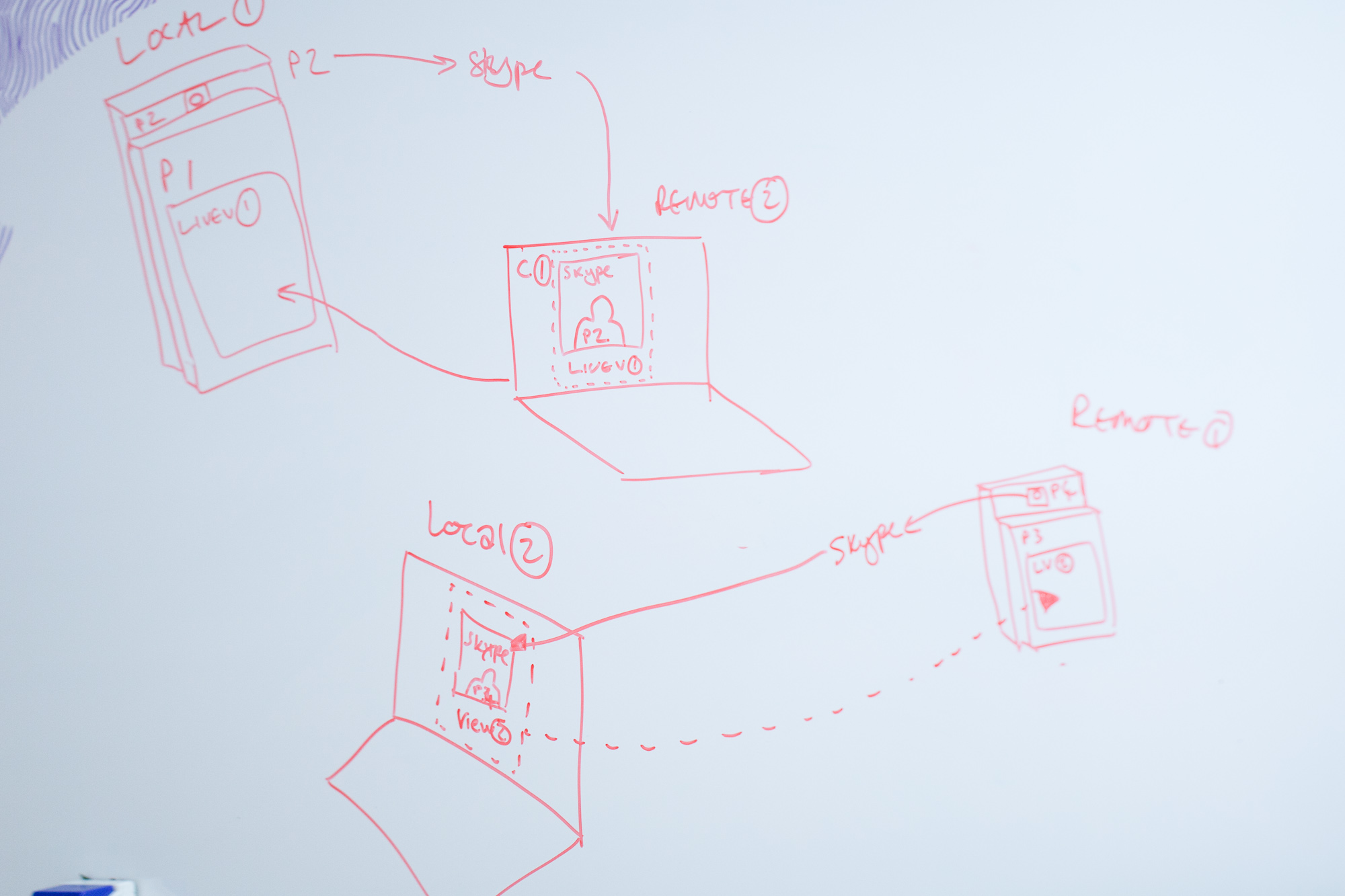

Our early sketches on both whiteboards and in these explorations then informed our prototyping efforts – firstly around the technical challenges of making a standalone product around google voice/video, and the second more focussed on the experiential challenges of making a simple, pleasurable domestic video chat device.

For reasons that might become obvious, the technical exploration became nicknamed “Polar Bear” and the experimental prototype “Domino”.

Prototype 1: A proof of technology called ‘Polar Bear’

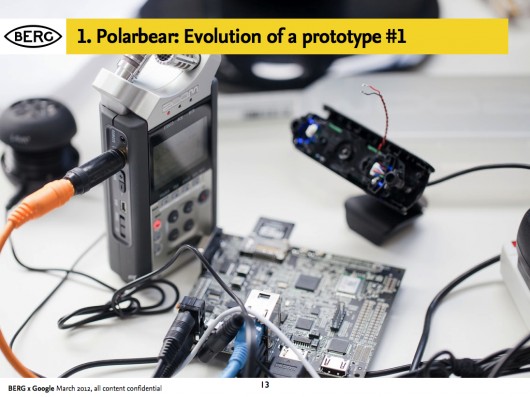

In parallel with the work to understand behaviours we also began exploring end-to-end technical proofs.

We needed to see if it was possible to make a technically feasible video-chat product with components that could be believable for mass-production, and also used open-standard software.

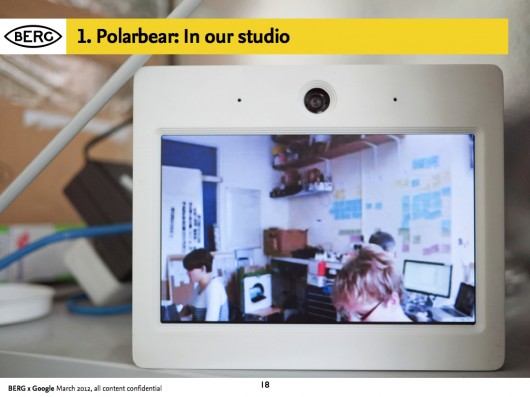

Aside from this, it provided us with something to ‘live with’, to understand the experience of having an always-on video chat appliance in a shared social space (our studio)

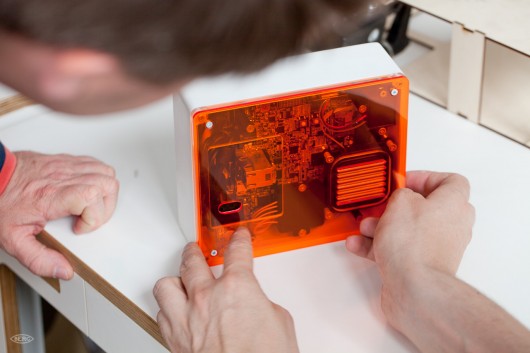

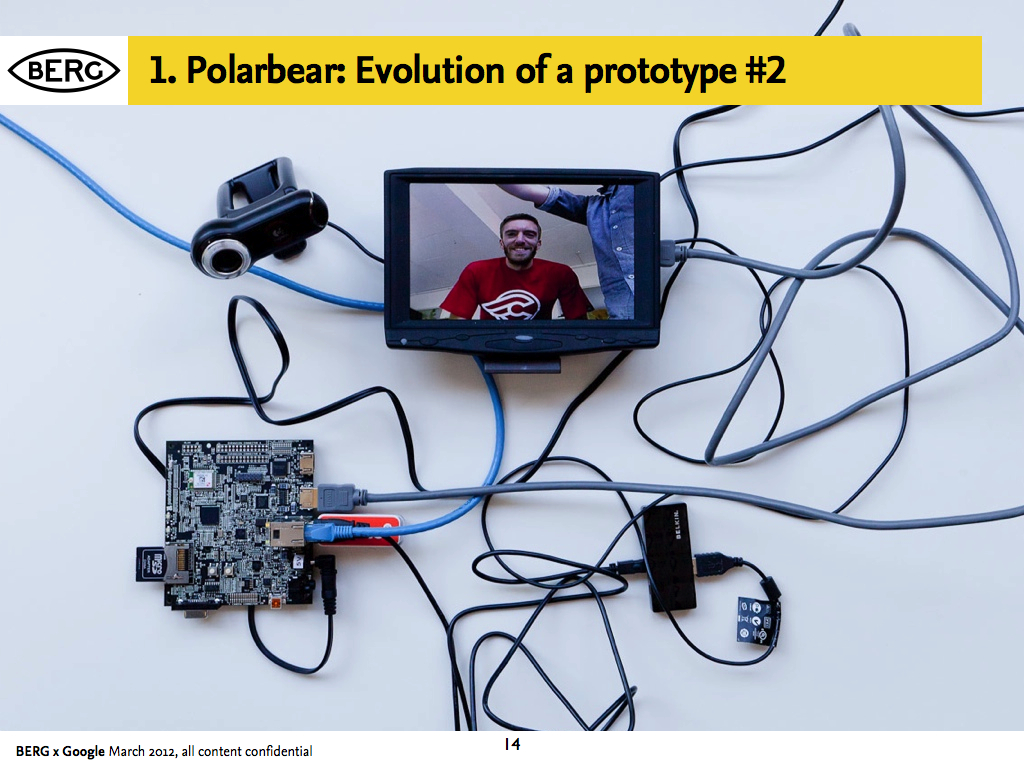

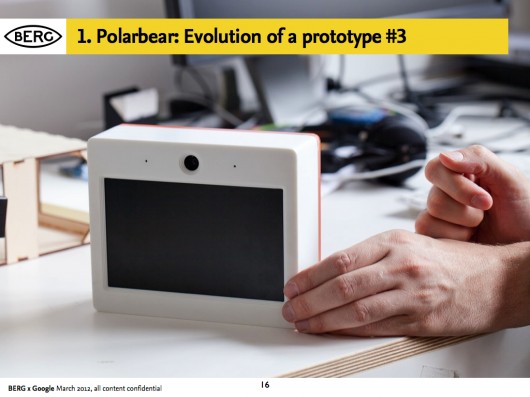

Andy and Nick worked closely with Tom and Durrell from Luckybite on housing the end-to-end proof in a robust accessible case.

It looked like a polar bear to us, and the name stuck…

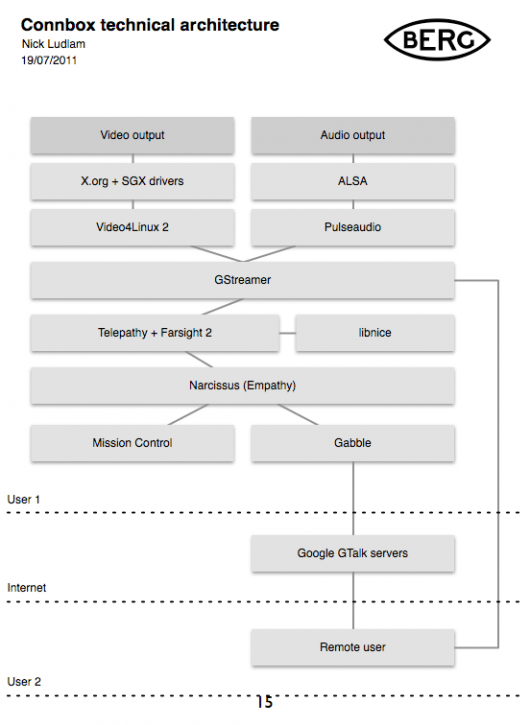

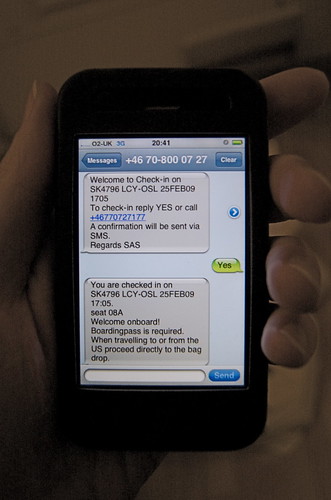

The software stack was designed to create something that worked as an appliance once paired with another, that would fire up a video connection with its counterpart device over wireless internet from being switched on, with no need for any other interface than switching it on at the plug.

We worked with Collabora to implement the stack on Pandaboards: small form-factor development boards.

Living with Polar Bear was intriguing – sound became less important than visual cues.

It reminded us all of Matt Webb’s “Glancing” project back in 2003:

Every so often, you look up and look around you, sometimes to rest your eyes, and other times to check people are still there. Sometimes you catch an eye, sometimes not. Sometimes it triggers a conversation. But it bonds you into a group experience, without speaking.

Prototype 2: A product and experience prototype called “Domino”

We needed to come up with new kinds of behaviours for an always on, domestic device.

This was the biggest challenge by far, inventing ways in which people might be comfortable opening up their spaces to each other, and on top of that, to create a space in which meaningful interaction or conversation might occur.

To create that comfort we wanted to make the state of the connection as evident as possible, and the controls over how you appear to others simple and direct.

The studio’s preoccupations with making “beautiful seams” suffused this stage of the work – our quest to create playful, direct and legible interfaces to technology, rather than ‘seamless’ systems that cannot be read or mastered.

In workshops with Luckybite, the team sketched out an approach where the state of the system corresponds directly to the physicality of the device.

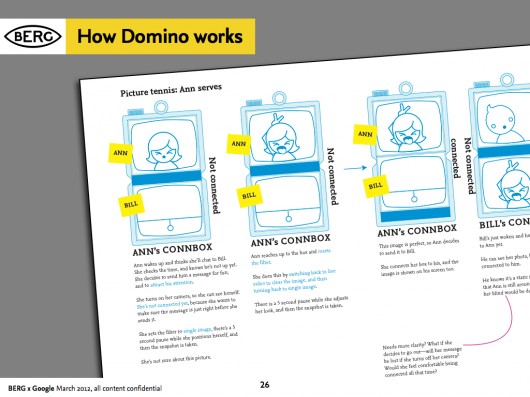

The remote space that you are connecting with is represented on one screen housed in a block, and the screen that shows your space is represented on another. To connect the spaces, the blocks are pushed together, and pulled-apart to disconnect.

Durrell outlined a promising approach to the behaviour of the product in a number of very quick sketches during one of our workshops:

Denise further developed the interaction design principles in a detailed “rulespace” document, which we used to develop video prototypes of the various experiences. This strand of the project acquired the nickname ‘Domino’ – these early representations of two screens stacked vertically resembling the game’s pieces.

As the team started to design at a greater level of detail, they started to see the issues involved in this single interaction: Should this action interrupt Ann in her everyday routine? Should there be a sound? Is a visual change enough to attract Ann’s attention?

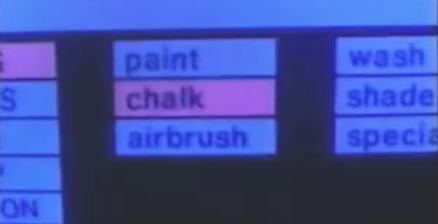

The work started to reveal more playful uses of the video connection, particularly being able to use ‘stills’ to communicate about status. The UI also imagines use of video filters to change the way that you are represented, going all the way towards abstracting the video image altogether, becoming visualisations of audio or movement, or just pixellated blobs of colour. Other key features such as a ‘do not disturb blind’ that could be pulled down onscreen through a physical gesture emerged, and the ability to ‘peek’ through it to let the other side know about our intention to communicate.

Product/ID development

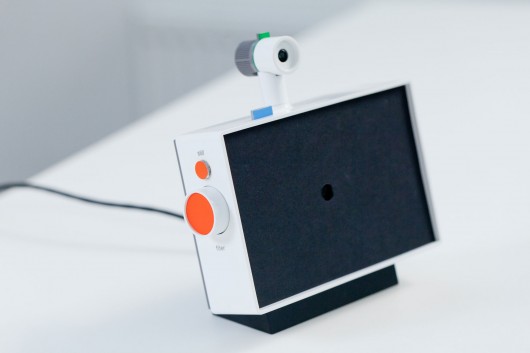

With Luckybite, we started working on turning it into something that would bridge the gap between experience prototype and product.

The product design seeks to make all of the interactions evident with minimum styling – but with flashes of Google’s signature colour-scheme.

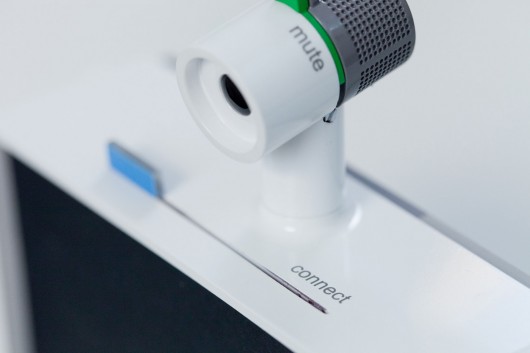

The detachable camera, with a microphone that can be muted with a sliding switch, can be connected to a separate stand.

This allows it to be re-positioned and pointed at other views or objects.

This is a link back to our early ‘material explorations’ that showed it was valuable to be able to play with the camera direction and position.

Prototype 3: Testing the experience and the UI

Final technical prototypes in this phase make a bridge between the product design and experience thinking and the technical explorations.

This manifested in early prototypes using Android handsets connected to servers.

Connbox: Project film

Durrell Bishop narrates some of the prototype designs that he and the team worked through in the Connbox project.

The importance of legible products

The Connbox design project had a strong thread running though it of making interfaces as evident and simple as possible, even when trying to convey abstract notions of service and network connectivity.

I asked Jack to comment on the importance of ‘legibility’ in products:

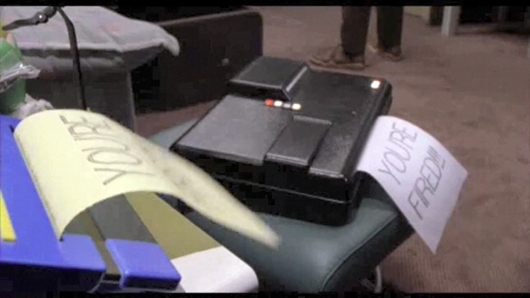

Connbox exists in a modern tradition of legible products, which sees the influence of Durrell Bishop. The best example I’ve come across that speaks to this thinking is Durrell’s answering machine he designed.

When messages are left on the answering machine they’re represented as marbles which gather in a tray. People play the messages by placing them in a small dip and when they’ve finished they replace them in the machine.

If messages are for someone else in the household they’re left in that persons bowl for later. When you look at the machine the system is clear and presented through it’s physical form. The whole state of the system is evident on the surface, as the form of the product.

Making technology seamless and invisible hides the control and state of the system – this path of thinking and design tries to place as much control as possible in the hands of the end-user by making interfaces evident.

In the prototype UI design, Joe created some lovely details of interaction fusing Denise’s service design sketches and the physical product design.

For instance, I love this detail where using the physical ‘still’ button, causes a digital UI element to ‘roll’ out from the finger-press…

A very satisfying dial for selecting video effects/filters…

And here, where a physical sliding tab on top of the device creates the connection between two spaces

This feels like a rich direction to explore in future projects, of a kind of ‘reverse-skeuomorphism‘ where digital and physical affordances work together to do what each does best rather than just one imitating the other.

Conclusion: What might have been next?

At the end of this prototyping phase, the project was put on hiatus, but a number of directions seemed promising to us and Google Creative Lab.

Broadly speaking, the work was pointing towards new kinds of devices, not designed for our pockets but for our homes. Further explorations would have to be around the rituals and experience of use in a domestic setting.

Special attention would have to be given to the experience of set-up, particularly pairing or connecting the devices. Would this be done as a gift, easily configured and left perhaps for a relative who didn’t have a smartphone or computer? How could that be done in an intuitive manner that emphasised the gift, but left the receiver confident that they could not break the connection or the product? Could it work with a cellular radio connection, in places where there no wireless broadband is found?

What cues could the physical product design give to both functionality and context? What might the correct ‘product language’ be for such a device, or family of devices for them to be accepted into the home and not seen as intrusive technology.

G+ and Hangouts launched toward the end of the project, so unfortunately there wasn’t time in the project to accommodate these interesting new products.

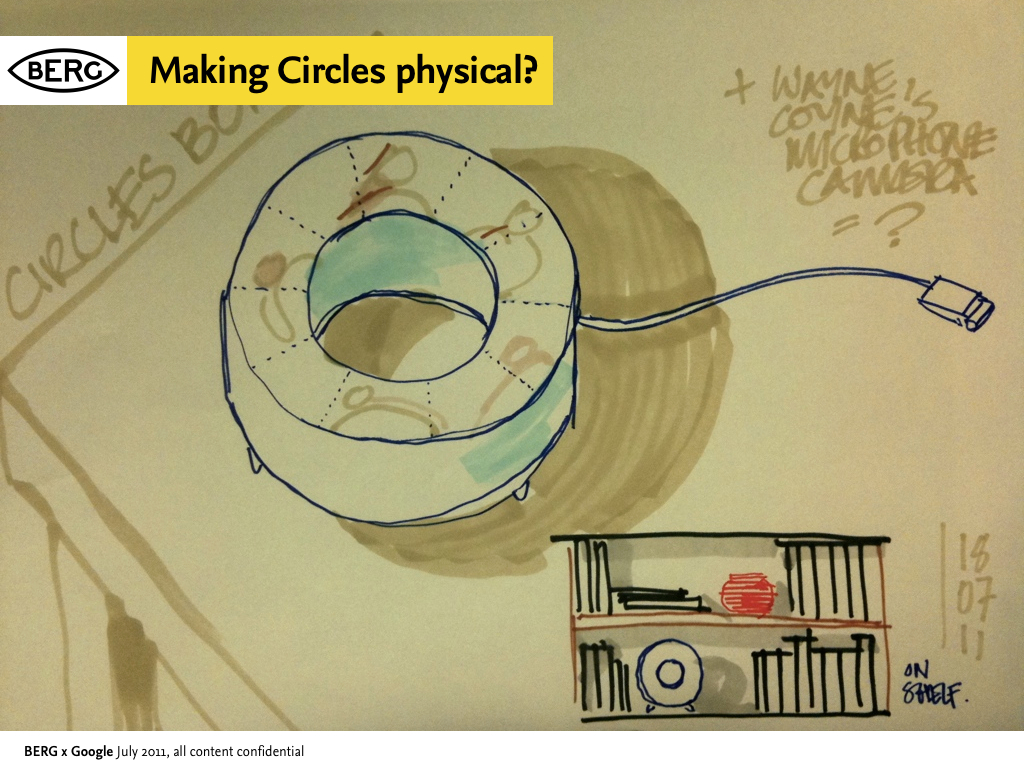

However we did start to talk about ways to physicalize G+’s “Circles” feature, which emphasises small groups and presence – it seemed like a great fit with what we had already looked at. How might we create a product that connects you to an ‘inner circle’ of contacts and the spaces they were in?

Postscript: Then and Now – how technology has moved on, and where we’d start now

Since we started the Connbox project in the Spring of 2011, one could argue that we’ve seen a full cycle of Moore’s law improve the capabilities of available hardware, and certainly both industry and open-source efforts in the domain of video codecs and software have advanced significantly.

Making Connbox now would be a very different endeavour.

Here Nick comments on the current state-of-the-art and what would be our starting points were we (or someone else) to re-start the project today…

Since we wrapped up this project in 2011, there’s been one very conspicuous development in the arena of video chat, and that is the rise of WebRTC. WebRTC is a draft web standard from W3C to enable browser to browser video chat without needing plugins.

As of early 2013, Google and Mozilla have demonstrated this system working in their nightly desktop browser builds, and recorded the first cross-browser video call. Ericsson are one of the first groups to have a mobile implementation available for Android and iOS in the form of their “Bowser” browser application.

WebRTC itself is very much an evolution of earlier work. The brainchild of Google Hangout engineers, this single standard is implemented using a number of separate components. The video and audio technology comes from Google in the form of the VP8 and iLBC codecs. The transport layer has incorporated libjingle which we also relied upon for our Polar Bear prototype, as part of the Farsight 2 stack.

Google is currently working on enabling WebRTC functionality in Chrome for Android, and once this is complete, it will provide the ideal software platform to explore and prototype Connbox ideas. What’s more, it actually provides a system which would be the basis of taking a successful prototype into full production.

Notable precedents

While not exhaustive, here are some projects, products, research and thinking we referenced during the work…

- RCA Helen Hamlyn Centre Video Chat Work

http://www.hhc.rca.ac.uk/3994-4006/all/1/Window-on-the-World.aspx - Push-to-talk and the intimacy it creates

http://www.purselipsquarejaw.org/2003_11_01_blogger_archives.php#106787988957888590 - Clearboard

http://web.media.mit.edu/~ishii/CB.html - Ambient Awareness

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ambient_awareness - Leisa Reichelt on Ambient intimacy

http://www.disambiguity.com/ambient-intimacy/ - Project Stargate (always-on Skype)

http://danielodio.com/project-stargate-always-on-skype-video-connection-for-remote-offices - Matt Webb’s Glancing project

http://interconnected.org/notes/2003/09/glancing/

Thanks

Massive thanks to Tom Uglow, Sara Rowghani, Chris Lauritzen, Ben Malbon, Chris Wiggins, Robert Wong, Andy Berndt and all those we worked with at Google Creative Lab for their collaboration and support throughout the project.

Thanks to all we worked with at Collabora and Future Platforms on prototyping the technology.

Big thanks to Oran O’Reilly who worked on the films with Timo and Jack.