Consider this a little bit of a call-and-response to our friends through the plasterboard, specifically James’ excellent ‘moodboard for unknown products’ on the RIG-blog (although I’m not sure I could ever get ‘frustrated with the NASA extropianism space-future’).

There are some lovely images there – I’m a sucker for the computer-vision dazzle pattern as referenced in William Gibson’s ‘Zero History’ as the ‘world’s ugliest t-shirt‘.

The splinter-camo planes are incredible. I think this is my favourite that James picked out though…

Although – to me – it’s a little bit 80’s-Elton-John-video-seen-through-the-eyes-of-a-‘Cheekbone‘-stylist-too-young to-have-lived-through-certain-horrors.

I guess – like NASA imagery – it doesn’t acquire that whiff-of-nostalgia-for-a-lost-future if you don’t remember it from the first time round. For a while, anyway.

Anyway. We’ll come back to that.

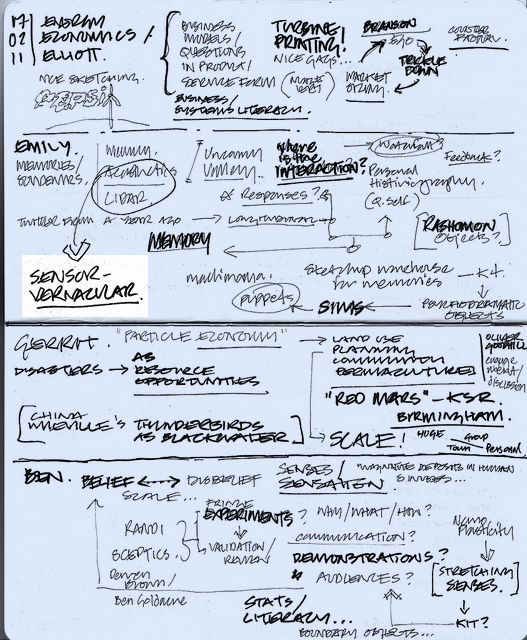

The main thing, is that James’ writing galvanised me to expand upon a scrawl I made during an all-day crit with the RCA Design Interactions course back in February.

‘Sensor-Vernacular’ is a current placeholder/bucket I’ve been scrawling for a few things.

The work that Emily Hayes, Veronica Ranner and Marguerite Humeau in RCA DI Year 2 presented all had a touch of ‘sensor-vernacular’. It’s an aesthetic born of the grain of seeing/computation.

Of computer-vision, of 3d-printing; of optimised, algorithmic sensor sweeps and compression artefacts.

Of LIDAR and laser-speckle.

Of the gaze of another nature on ours.

There’s something in the kinect-hacked photography of NYC’s subways that we’ve linked to here before, that smacks of the viewpoint of that other next nature, the robot-readable world.

Photo credit: obvious_jim

The fascination we have with how bees see flowers, revealing animal link between senses and motives. That our environment is shared with things that see with motives we have intentionally or unintentionally programmed them with.

As Kevin Slavin puts it – the things we have written that we can no longer read.

Nick’s being playing this week with http://code.google.com/p/structured-light/, and made this quick (like, in a spare minute he had) sketch of me…

The technique has been used for some pretty lovely pieces, such as this music video for Broken Social Scene.

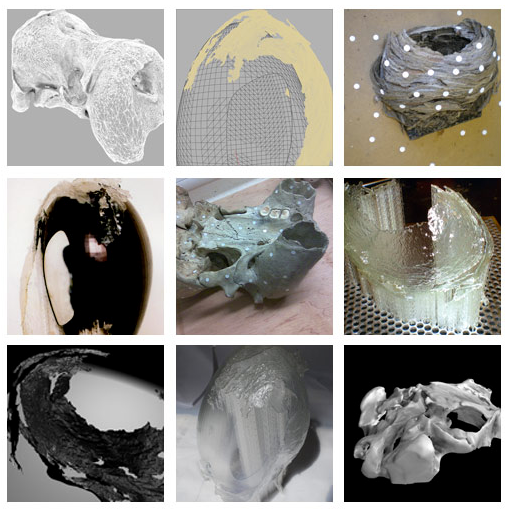

In particular, for me, there is something in the loop of 3d-scanning to 3d-printing to 3d-scanning to 3d-printing which fascinates.

It’s the lossy-ness that reveals the grain of the material and process. A photocopy of a photocopy of a fax. But atoms. Like the 80’s fanzines, or old Wonder Stuff 7″ single cover art. Or Vaughn Oliver, David Carson.

It is – perhaps – at once a fascination with the raw possibility of a technology, and – a disinterest, in a way, of anything but the qualities of its output. Perhaps it happens when new technology becomes cheap and mundane enough to experiment with, and break – when it becomes semi-domesticated but still a little significantly-other.

When it becomes a working material not a technology.

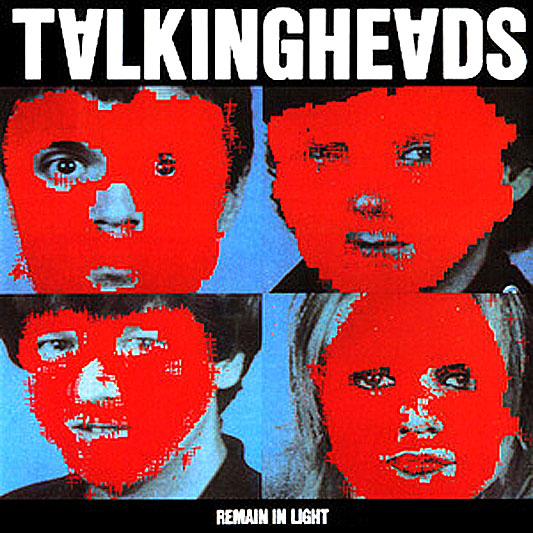

We can look back to the 80s, again, for an early digital-analogue: what one might term ‘Video-Vernacular’.

Talking Heads’ cover art for their album “Remain In Light” remains a favourite. It’s video grain / raw quantel as aesthetic has a heck of a punch still.

I found this fascinating from it’s wikipedia entry:

“The cover art was conceived by Weymouth and Frantz with the help of Massachusetts Institute of Technology Professor Walter Bender and his MIT Media Lab team.

Weymouth attended MIT regularly during the summer of 1980 and worked with Bender’s assistant, Scott Fisher, on the computer renditions of the ideas. The process was tortuous because computer power was limited in the early 1980s and the mainframe alone took up several rooms. Weymouth and Fisher shared a passion for masks and used the concept to experiment with the portraits. The faces were blotted out with blocks of red colour.

The final mass-produced version of Remain in Light boasted one of the first computer-designed record jackets in the history of music.”

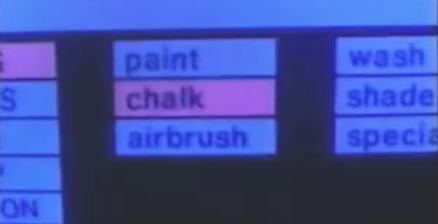

Growing up in the 1980s, my life was saturated by Quantel.

Quantel were the company in the UK most associated with computer graphics and video effects. And even though their machines were absurdly expensive, even in the few years since Weymouth and Fisher harnessed a room full of computing to make an album cover, moore’s law meant that a quantel box was about the size of a fridge as I remember.

Their brand name comes from ‘Quantized Television’.

Awesome.

As a kid I wanted nothing more than to play with a Quantel machine.

Every so often there would be a ‘behind-the-scenes’ feature on how telly was made, and I wanted to be the person in the dark illuminated by screens changing what people saw. Quantizing television and changing it before it arrived in people homes. Photocopying the photocopy.

Alongside that, one started to see BBC Model B graphics overlaid on video and TV. This was a machine we had in school, and even some of my posher friends had at home! It was a video-vernacular emerging from the balance point between new/novel/cheap/breakable/technology/fashion.

Kinects and Makerbots are there now. Sensor-vernacular is in the hands of fashion and technology now.

In some of the other examples James cites, one might even see ‘Sensor-Deco’ arriving…

James certainly has an eye for it. I’m going to enjoy following his exploration of it. I hope he writes more about it, the deeper structure of it. He’ll probably do better than I am.

Maybe my response to it is in some ways as nostalgic as my response to NASA imagery.

Maybe it’s the hauntology of moments in the 80s when the domestication of video, computing and business machinery made things new, cheap and bright to me.

But for now, let me finish with this.

There’s both a nowness and nextness to Sensor-Vernacular.

I think my attraction to it – what ever it is – is that these signals are hints that the hangover of 10 years of ‘war-on-terror’ funding into defense and surveillance technology (where after all the advances in computer vision and relative-cheapness of devices like the Kinect came from) might get turned into an exuberant party.

Dancing in front of the eye of a retired-surveillance machine, scanning and printing and mixing and changing. Fashion from fear. Quantizing and surprising. Imperfections and mutations amplifying through it.

Beyonce’s bright-green chromakey socks might be the first, positive step into the real aesthetic of the early 21st century, out of the shadows of how it begun.

Let’s hope so.