The studio is continually interested in the beautiful and inventive stuff that can happen when you poke and prod around the edges of technology and culture. Mag+ emerged from a curiosity from both Bonnier and BERG about reading on tablets while Making Future Magic emerged from experiments with light painting and screens.

Early last year we were experimenting with product photography for a retail client pitch. We wondered how we could we use cinematic techniques to explore product imagery.

Watch the video of our experiments on Vimeo.

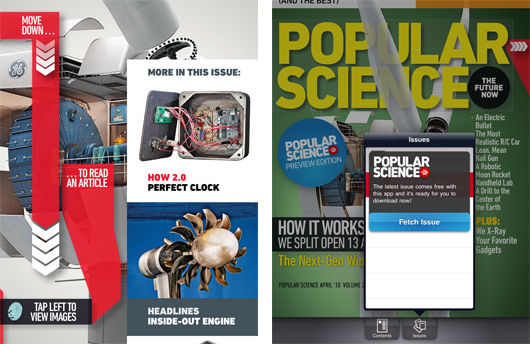

What would happen if instead of a single product image or a linear video, we could flick and drag our way through time and the optical qualities of lenses? What if we had control of the depth of field, focus, lighting, exposure, frame-rate or camera position through tap and swipe?

Swiping through cinema

This is a beautiful 1960’s Rolex that we shot in video while pulling focus across the surface the watch. On the iPad, the focus is then under your control, the focal point changes to match your finger as it taps and swipes across the object. Your eye and finger are in the same place, you are in control of the locus of attention.

Jack originally explored focus navigation (with technical help by George Grinsted) in 2000, and now Lytro allow ‘tap to focus’ in pictures produced by the ‘light field camera‘.

The lovely thing here is that we can see all of the analogue, optical qualities such as the subtle shifts in perspective as the lens elements move, and the blooming, reflection and chromatic abberations that change under our fingertips. Having this optical, cinematic language under the fine control of our fingertips feels new, it’s a lovely, playful, explorative interaction.

Orson Welles’ Deep Focus.

Cinematic language is a rich seam to explore, what if we could adjust the exposure to get a better view of highlights and shadows? Imagine this was diamond jewellery, and we could control the lighting in the room. Or to experiment with aperture, going from the deep focus of Citizen Kane, through to the extremely shallow focus used in Gomorrah, where the foreground is separated from the environment.

Cold Dark Matter by Cornelia Parker.

What if we dropped or exploded everyday objects under a super high-frame rate cinematography, and gave ourselves a way of swiping through the chaotic motion? Lots of interesting interactions to explore there.

Touching through glass

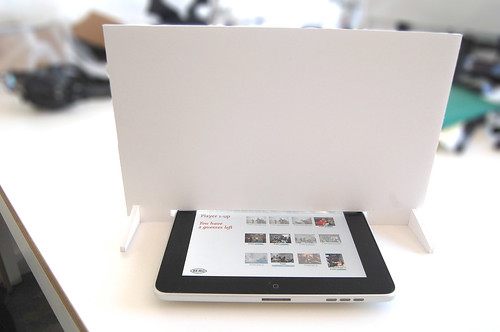

This next experiment really fascinated us. We shot a glass jar full of thread bobbins rotating in front of the camera, on the iPad you can swipe to explore these beautiful, intricate colourful objects.

There is a completely new dimension here, in that you are both looking at a glass jar and touching a cold glass surface. The effect is almost uncanny, a somewhat realistic sense of touch has been re-introduced into the cold, smooth iPad screen. We’re great fans of Bret Victor’s brilliant rant on the problems of the lack of tactility in ‘pictures under glass‘, and in a way this is a re-inforcement of that critique: tactility is achieved through an uncanny visual re-inforcement of touching cold glass. This one really needs to be in your hands to be fully experienced.

And it made us think, what if we did all product photography that was destined for iPads inside gorgeous Victorian bell jars?

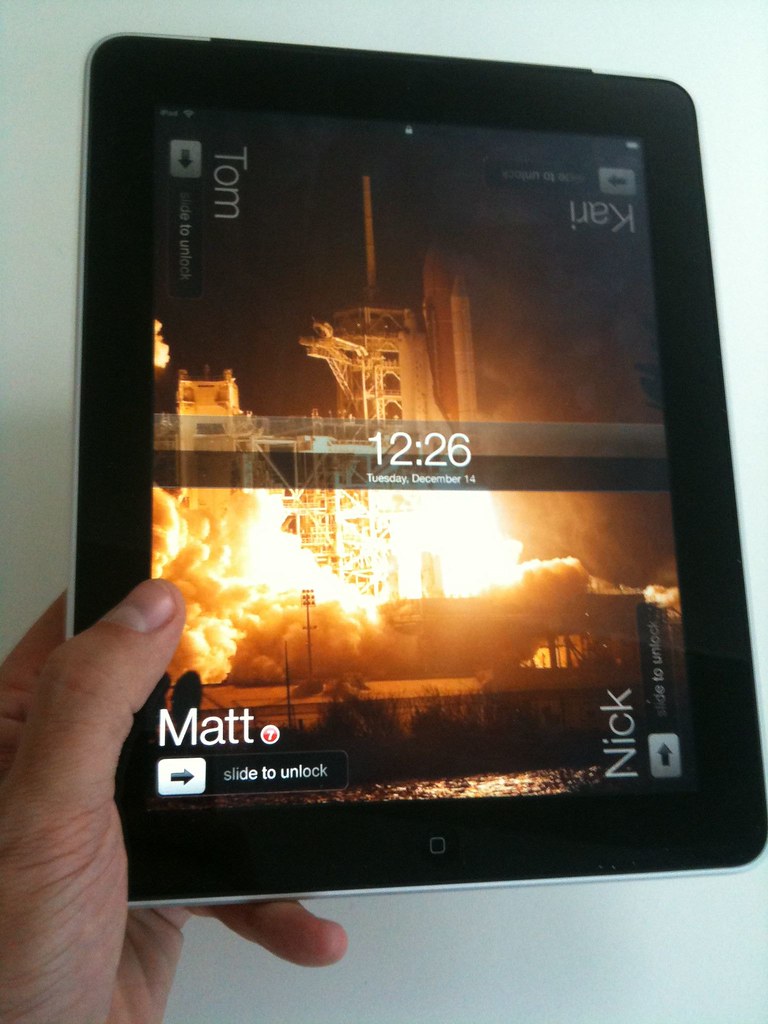

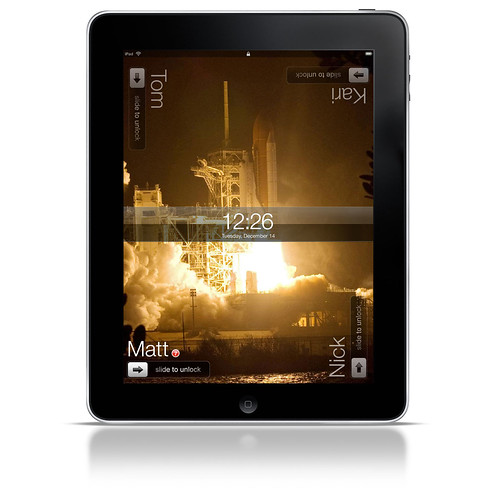

Nick realised this as an App on a first-generation iPad:

Each of the scenes in the Swiping through Cinema app are made up of hundreds (and in some cases thousands) of individual images, each extracted from a piece of real-time HD video. It is the high speed manipulation of these images which creates one continuous experience, and has only become possible relatively recently.

During our time developing Mag+, we learnt a great deal about using images on tablets. With the first-generation iPad, you needed to pay careful attention to RAM use, as the system could kill your app for being excessively greedy, even after loading only a handful of photographs. We eventually created a method which would allow you to smoothly animate any number of full-screen images.

With that code in place, we moved onto establishing a workflow which would allow us to shoot footage and be able to preview it within the app in a matter of minutes. We also consciously avoided filling the screen with user interface elements, which means that the only interaction is direct manipulation of what you see on-screen.

With the Retina display on the third-generation iPad, we’re really excited by the prospect of being able to move through super crisp and detailed image sequences.

We’re really excited about re-invigorating photographic and cinematographic techniques for iPads and touchscreens, and finding out how to do new kinds of interactive product imagery in the process.