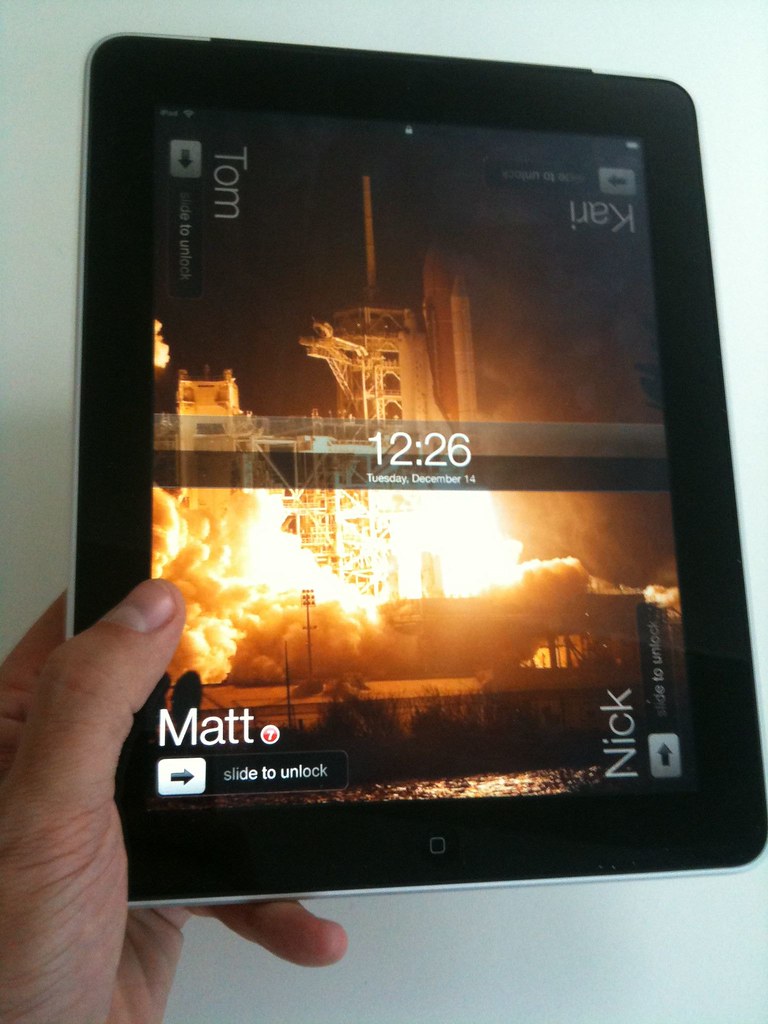

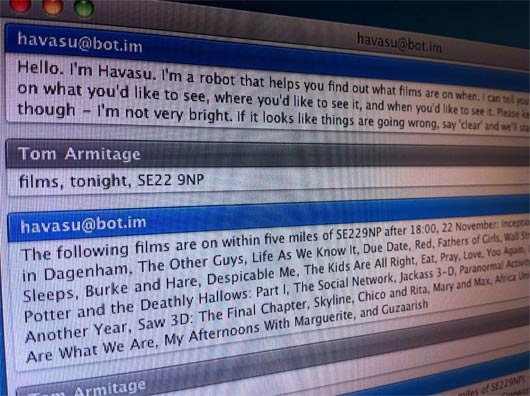

When we first started discussing Havasu, I prepared some notes around the topic: prior art, interesting ideas about language we might like to include, interfaces that are more conversational than you might expect. I thought it might be worthwhile sharing that list – not only to show you what was going around my head whilst I was building Havasu, but also because I think it’s interesting. Here’s what I wrote.

Friend-of-Berg Tom Carden wrote this four years ago, about a to-do list shaped like a push-pull stack, that’s addressed over IM. There’s only one bot, which every user talks to privately. But most important was this line:

“It’s a chatbot rather than a command line utility or a website because I want it to follow me home and I want it to be private and immediate.”

Private and immediate feels important.

These are proposed by the philosopher Paul Grice, and are a fair dissection of what conversation looks like. They’re also great guidelines for UI. Consider the Maxim of Quantity:

- Make your contribution as informative as is required for the current purposes of the exchange.

- Do not make your contribution more informative than is required.

The former is obvious, but the latter’s as important in conversational interfaces – by not offering up too much, you help restrict the types of information a user will return.

Matt W pointed out to me that the most important part of the maxims is the foundation they’re built upon – the Co-operative Principle, which he explained thus (again, on Interconnected, a few years ago):

“Participants assume that a speaker is being cooperative, and thus they make conversational implicatures about what is said”. What this means is that the bot must make maximum use of all that the user [interviewer?] has said, or at least make conversationally clear what’s understood and not.

These have come up in conversation from time-to-time over the years. They’re the founding principles Jellyvision used when building videogame-cum-quiz-show You Don’t Know Jack.

The PDF is clear, concise, and right about many things. They feel a lot like Grice’s Maxims for interactive forms of media; very much required reading if you’re interested in conversational UI. I’d end up reproducing the whole thing if I’m not careful, so instead, one quotation about conversations, which Jeff Atwood cited in 2004:

in a conversation, you can’t unilaterally decide what gets discussed. The other person is not a machine. He can place his own limits on the conversation. He can steer the conversation in one direction, just as much as you can. The control of the conversation is shared.

Interactive Fiction

I’m a fan of Interactive Fiction – which is generally used to refer to what once might have been called “text adventures”.

Some IF games like to play games with the parser itself – the interface the player uses to interact with the game world.

Violet turns the parser into a character. It’s not just the interface that understands the player’s language; it’s an imagined version of the player character’s absent girlfriend, pleading with him to finish the thesis he promised he would. Failure in the game is responded to with polite disappointment; misunderstanding the player’s intention turns to sweet confusion. The parser doesn’t have a personality; it’s adopting a persona. It gives the parser a softer, more tolerant feeling than one that says “command not recognised” or “I can’t do that”.

(Violet, is, incidentally, my primary recommendation for anyone looking to try IF at the moment).

Lost Pig is a game about an orc, called Grunk, who has lost a pig. Grunk is somewhat stupid – he’s nowhere near as literate as the player. As such, you realise you’re “commanding” someone less intelligent than you, and are less surprised when they’re stupid or can’t understand. You also end up keeping your instructions much simpler. Again, an example of how the language/tone of the interface alters how users address it, without having to provide direct instructions on the sort of language necessary to communicate with it.

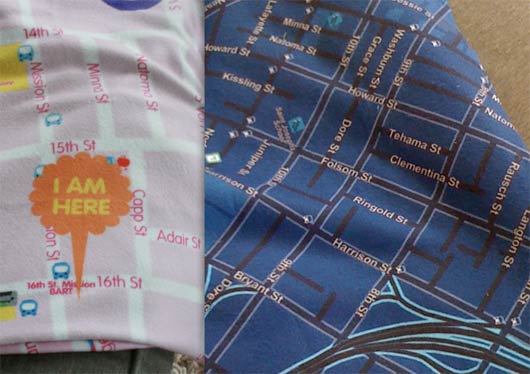

SNAP appears in my existing information flows – in the original example we supplied, RSS. It politely observes the conventions of that space. Conversational UI should do this, too – if a UI is going to exist on Twitter, it should be well- behaved and follow the conversations of the space. So, in the case of a Twitter bot, it shouldn’t be high-traffic; it shouldn’t hold conversations in public that ought to be private.

By making a parser/client/bot that’s only as smart as it need to be, you don’t get the cognitive dissonance of something that looks smart but falls apart when you get your syntax wrong. (Compare, for instance, with Applescript or ELIZA). Good bots don’t pretend to be anything they’re not.

From this point I got thinking about BEAM robots, and specifically, the way that approach considers sensors.

So: if you know what appendages a bot has, you know what it’s capable of. And so, really, a chatbot shouldn’t pretend to have eyes and ears – or “see” or “hear” – because it doesn’t. It has a text parser; it has scrapers; it has rules. Finding a way to be honest in the parser without using inaccurate metaphors is important.

BASAAP also suggests lots of little, single purpose bots, acting together. Matt J and I chatted about this and discussed the idea of things that aren’t really things – Twitter lists, groupings of friends in Facebook or IM, to-do lists, calendars – gaining little, chatty, BASAAP AIs that represent them and act as conversational UIs to them

Another take on many-small-bots, in an old post from Matt W’s blog:

“The user path has to be short… Instead of one bot, have several”.

Several bots again. I like the idea that the bot is the “verb” – rather than choosing complicated instructions to tell one bot, you choose the appropriate bot for the task, and then tell it simple things. Choosing a bot narrows what you’re going to say.

If bots are to communicate with one another, could that be public too? Everyone should use the same messaging bus, human or machine. If I talk to them on Twitter, they should talk to one another on Twitter. Unless it can’t be avoided, but then they should at least talk about it. (“I sent JohnBot a package of binary data too big to put here.”)

Nonne and Num

This is a personal thing I always come back to, and here seems relevant to talking to bots in simple language. Nonne and num are words in Latin that appear in questions, and all they really do is indicate the expected answer. They are sometimes loosely translated as “surely”. For instance: “Surely you’re coming out with us on Friday night?” is a nonne question, and “surely you’re not going to eat that?” is a num question.

I like the idea that you can shape the language someone will use in an answer by the language you ask the question in. What are the equivalents in a conversational UI?

Packrati.us is a nifty service – it watches your Twitter stream, and when you post any links, it automatically posts them to Delicious for you. So it’s not conversational like a chatbot, but it’s conversational like Lanyrd is – it’s a polite listener, eavesdropping, and being useful/busy in the background, but not overstepping its boundaries.

Moving a conversation between platforms

When I first wrote chatbots, more of my conversation happened on IM. Now, IM is reserved for more higher priority conversation; I tned to use Twitter for low-level, occasional banter, like sending URLs to friends. I like the idea that a conversation might move between platforms – an eavesdropping bot might work things out from my Twitter stream and trickle information back to me; but, if it needed something detailed, or urgent, or required information that could only really emerge in a conversation… an IM bot could take over the same conversation. And when it was done, the outcome and remaining announcements would flow back somewhere else.