Ericsson’s UX Lab have recently been doing some important and brave work around the Internet of Things. We have been particularly intrigued by their concept of using social networks as a model to understand complex networks.

This is smart, it builds on our innate familiarity with social networks, but also acts as a provocation for us to think differently about the internet of things. It also happens to cross over with many of the BERG’s interests including Little Printer, BERGCloud and very close to the ‘Products are people too‘ concept that has been guiding much of our work.

So over the last few months BERG and Ericsson have been working in partnership to explore some practical and poetic approaches to networks and smart products. We have been developing concepts around the rituals and rhythms of life with connected things, and creating some visualisations based on network behaviours. Phase 1 of this project is complete, and although we can’t talk about the entire project, we thought it would be good to show some of our first sketches.

You can also read more about the collaboration from Ericsson’s perspective here.

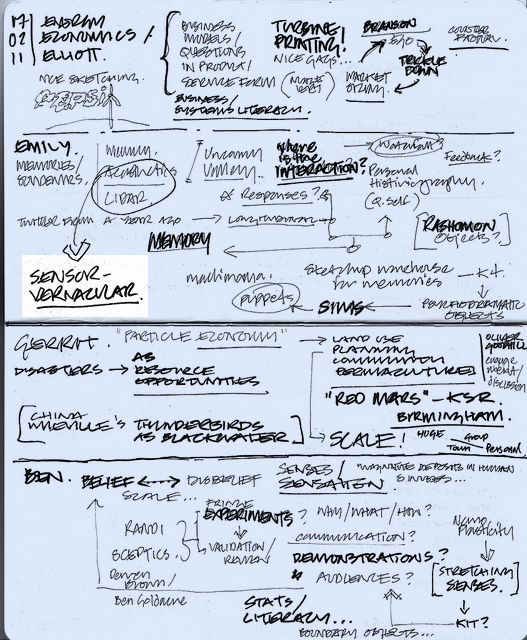

We kicked off in a product invention workshop where some really strong themes emerged.

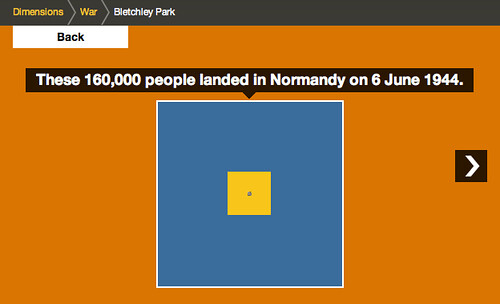

There are huge areas of network-ness, from the infrastructure to the protocols, from the packets to the little blinking lights on our routers, that are largely ‘dark matter‘: immaterial and invisible things that are often misunderstood, mythologised or ignored.

There are a few long-term efforts to uncover the physical infrastructure of our networks. Ericsson itself has long understood the need to both explain the technology of networks and their effects.

But – we mostly feel like the network is out of our control – tools to be able to satisfyingly grasp and optimise our own networks and connected products aren’t yet available to us. Working towards products, services and visualisations that make these things more legible and tangible is good!

Joyful (net)work: Zen Garden Router

Inspired by Matt Jones’ idea of a ‘Zen garden router’ this video sketch focuses on the ongoing maintenance and ‘tuning’ of a domestic ecosystem of connected products, and the networks that connect them. We have modified a standard router with a screen on its top surface, to make network activity at various scales visible and actionable at the point at which it reaches the house. We’ve used a version of the beautiful ‘Toner’ maps by our friends at Stamen in the design.

This looks to metaphors of ‘joyful work’ that we engage with already domestically – either mechanisms or rituals that we find pleasurable or playful even if they are ‘work’. Here there are feedback mechanisms that produce more affect and pleasure – for instance the feedback involved in tuning a musical instrument, sound system or a radio. Gardening also seems to be a rich area for examination – where there is frequent work, but the sensual and systemic rewards are tangible.

Network Murmurations

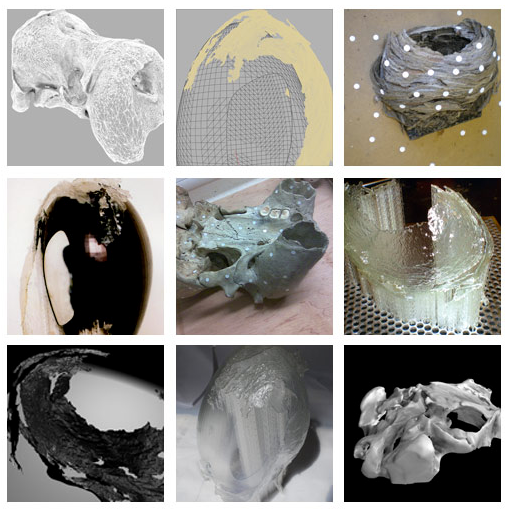

Different network activity has vastly different qualities. This is an experiment using projection mapping to visualise network activity in the spaces that the network actually inhabits.

When loading a web page a bunch of packets travel over WiFi in a dense flock. While playing internet video packets move in a dense stream that persists as long as the video is playing. On the other end of the scale a Bluetooth mouse or a Zigbee light switch where tiny, discrete amounts of data flow infrequently. Then there are ‘collisions’ in the network flow or ‘turbulence’ created by competing devices such as microwaves or cordless phones.

We use as inspiration a ‘murmuration‘ of starlings, a beautiful natural phenomenon. In this visualisation the ‘murmuration’ flits between devices revealing the relationships and the patterns of network traffic in the studio. Although this sketch isn’t based on actual data on network traffic, it could be, and it seems that there is great scope in bringing more network activity to our attention, giving us a sense of its flows and patterns over time.

The network is part of our everyday lives. Seeing the network is the first step to understanding the network, acting on it, and gaining an everyday literacy in it. So what should it look like? These video sketches are part of our ongoing effort to find out – a glimpse of our first phase of research, there is more work in the pipeline that we hope to be able to talk about soon.

Thanks to the Ericsson’s UX Lab for being great R&D partners.