Matt’s mentioned in the past few summaries of weeks that I’ve been working on ‘material exploration’ for a project called Ashdown. I wanted to expand a little on what material exploration looks like for code and what it feels like to me, because it feels like a strange and foreign territory at times. This is my second material exploration of data for BERG, the first being at the beginning of the Shownar project.

There are several aspects to this post. Partly, it’s about what material explorations look like when performed with data. Partly, it’s about the role of code as a tool to explore data. We don’t write about code much on the site, because we’re mainly interested in the products we produce and the invention involved in them, but it’s sometimes important to talk about processes and tools, and this, I feel, is one of those times. At the same time, as well as talking about technical matters, I wanted to talk a little about what the act of doing this work feels like.

Programmers very rarely talk about what their work feels like to do, and that’s a shame. Material explorations are something I’ve really only done since I’ve joined BERG, and both times have felt very similar – in that they were very, very different to writing production code for an understood product. They demand code to be used as a sculpting tool, rather than as an engineering material, and I wanted to explain the knock-on effects of that: not just in terms of what I do, and the kind of code that’s appropriate for that, but also in terms of how I feel as I work on these explorations. Even if the section on the code itself feels foreign, I hope that the explanation of what it feels like is understandable.

Material explorations

BERG has done material explorations before – they were a big part of our Nokia Personalisation project, for instance – and the value of them is fairly immediate when the materials involved are things you can touch.

But Ashdown is a software project for the web – its substrate is data. What’s the value of a material exploration with an immaterial substrate? What does it look like to perform such explorations? And isn’t a software project usually defined before you start work on it?

Not always. Invention comes from design, and until the data’s been exposed to designers in a way that they can explore it, and manipulate it, and come to an understanding of what design is made possible by the data, there essentially is no product. To invent a product, we need to design, and to design, we need to explore the material. It’s as simple as that.

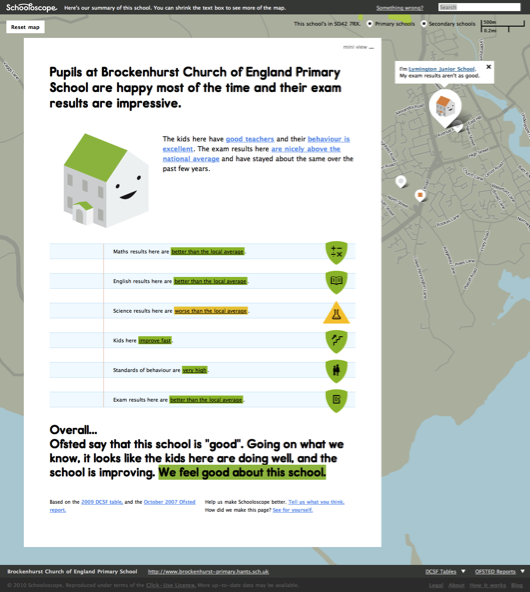

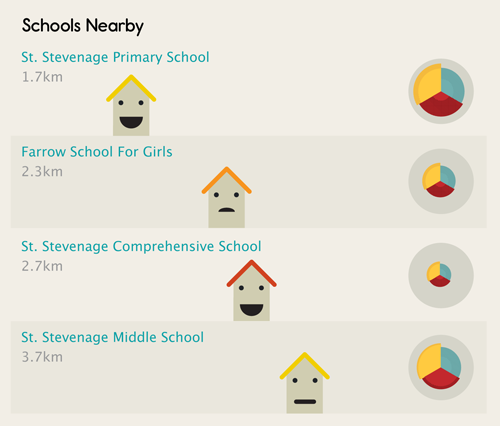

There’s a lot of value in this process. We know, at a high level, what the project’s about: in the case of Ashdown, Matt’s described it as “a project to bring great user experience to UK education data“. The high level pitch for the project is clear, but we need to get our hands mucky with the data to answer some more significant questions about it: what will it do? What will it feel like to use? What are the details of that brief?

The goals of material exploration

There are several questions that the material exploration of data seeks to answer:

- What’s available: what datasets are available? What information is inside them? How easily are they to get hold of – are they available in formatted datasets or will they need scraping? Are they freely available or will they need licensing?

- What’s significant: it’s all very well to have a big mass of data, but what’s actually significant within it? This might require datamining, or other statistical analysis, or getting an expert eye on it.

- What’s interesting: what are the stories that are already leaping out of the data? If you can tell stories with the data, chances are you can build compelling experiences around it.

- What’s the scale: getting a good handle on the order of magnitude helps you begin to understand the scope of the project, and the level of details that’s worth going into. Is the vast scale of information what’s important, or is it the ability to cherry-pick deep, vertical slices from it more useful? That answer varies from project to project.

- What’s feasible: this goes hand in hand with understanding the scale; it’s useful to know how long basic tasks like parsing or importing data take to know the pace the application can move at, or what any blockers to a realistic application are. There is lots of scope to improve performance later, but knowing the limitations of processing the dataset early on helps inform design decisions.

- Where are the anchor points: this ties into “what’s significant”, but essentially: what are the points you keep coming back to – the core concepts within the datasets, that will become primary objects not just in the code but in the project design?

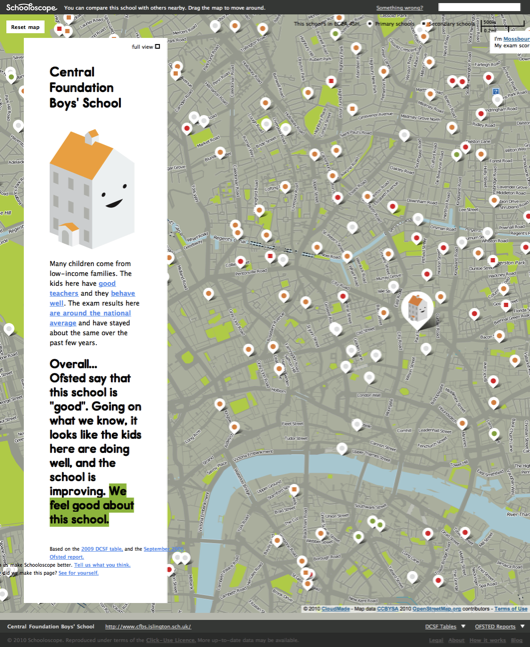

- What does it afford?: By which I mean: what are the obvious hooks to other datasets, or applications, or processes. Having location data affords geographical visualisation – maps – and also allows you to explore proximity; having details of Local Education Authorities allows you to explore local politics. What other ideas immediately leap into mind from exploring the data?

To explore all these ideas, we need to shape the data into something malleable: we need to apply a layer of code on the top of it. And it can’t just exist as code: we also need the beginnings of a website.

This won’t be the final site – or even the final code – but it’s the beginnings of a tool that can explain the data available, and help explore them, to designers, developers, and other project stakeholders, and that’s why it’s available, as early as possible, as an actual site.

To do this, the choice of tools used is somewhat important, but perhaps more important is the approach: keeping the code malleable, ensuring no decisions are too binding, and not editorialising. “Show everything” has become a kind of motto for this kind of work: because no-one else knows the dataset yet, it’s never worth deeming things “not worth sharing” yet. Everything gets a representation on the site, and then informed design decisions can be made by the rest of the team.

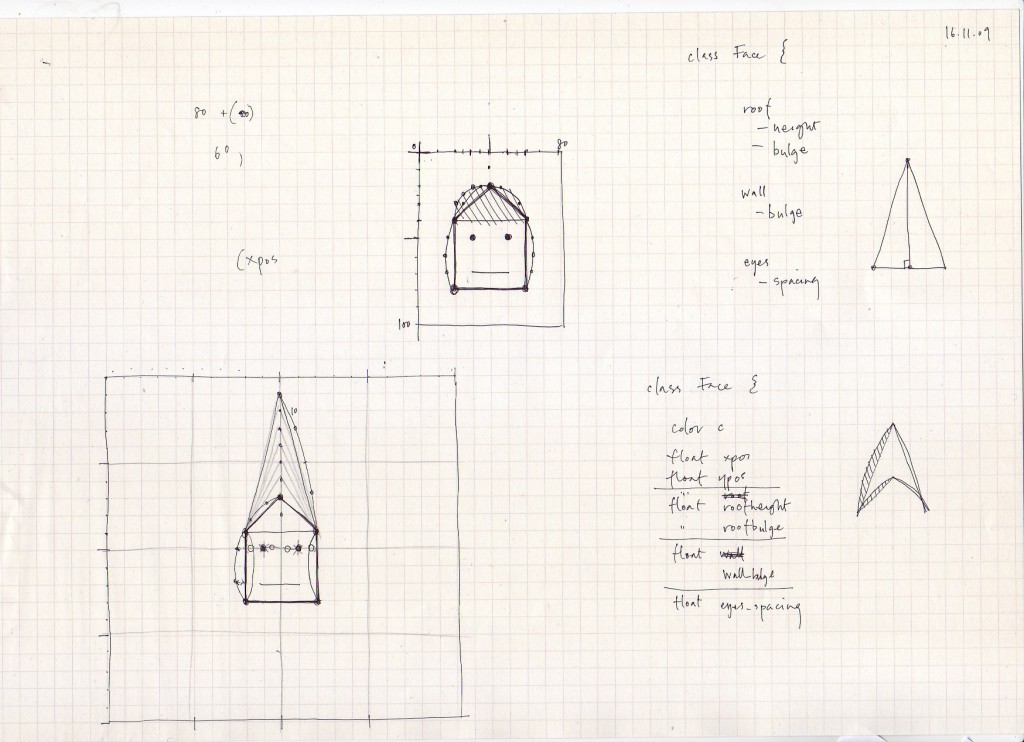

What does the code for such explorations look like?

It’s a bit basic. Not simple, but we’re not going to do anything clever: architecture is not the goal here. It will likely inform the final architecture, and might even end up being re-used, but the real goal is to get answers out of the system as fast as possible, and explore the scale of the data as widely as possible.

That means doing things like building temporary tables or throwaway models where necessary: speed is more important than normalisation, and, after all, how are you going to know how to structure the data until you’ve explored it?

Also, because we’re working on very large chunks of data, it’s important that any long running processes – scrapers, parsers, processors – need to be really granular, and able to pick up where they left off; my processing tasks usually only do one thing, and require running in order, but it’s better than one long complex process that can’t be restarted – if that falls over in the middle and can’t be restarted, it’s a lot of time (a valuable resource at these early stages) wasted.

It’s also important that there’s a suitably malleable interface to the data for you, the developer. For me, that’s a REPL/console of some sort – something slightly higher level than a MySQL terminal, that lets you explore codified representations of data (models) rather than just raw information. Shownar was built in PHP, and whilst it was, for many reasons, the right choice of platform for the project, I missed having a decent shell interface onto the system. On Ashdown, I’m working in Rails, and already the interactive console has made itself indispensable. For a good illustration of the succinct power of REPLs, and why they’re a useful thing to have around for data exploration, it’s definitely worth reading Simon Willison’s recent post on why he likes Redis.

Visualisation

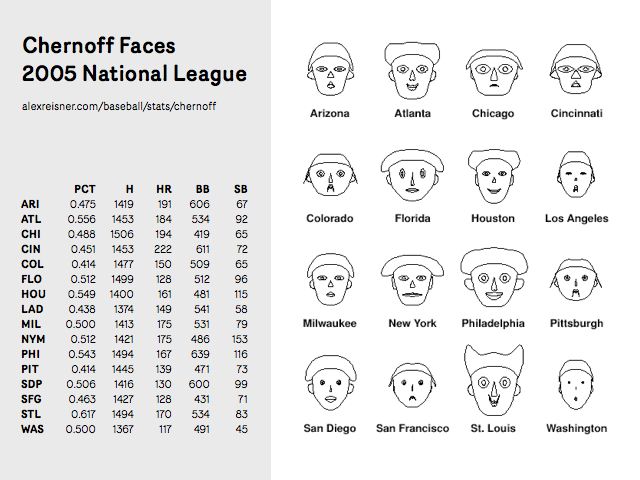

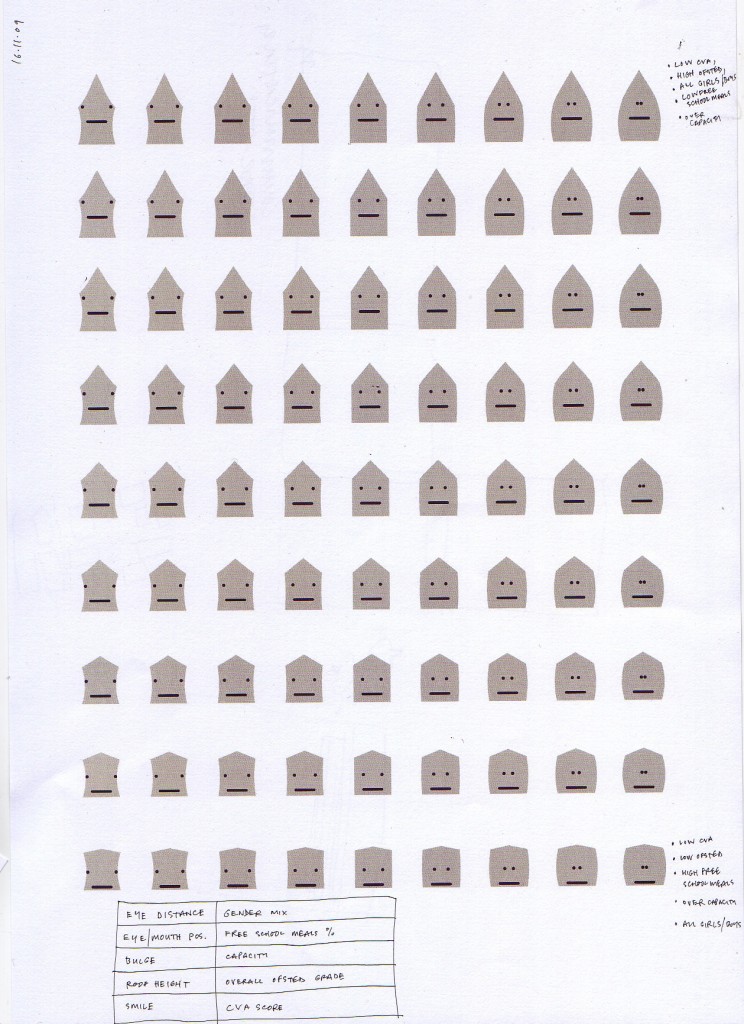

Visualisation is a really important part of the material exploration process. When it comes to presenting our explorations, it’s not just enough to have big lists, and vast, RESTful interfaces on top of blobs of data: that’s still not a very effective translation of the stories the data tells. Right now, we don’t need to be fussy about what we visualise: it’s worth sticking graphs everywhere and anywhere we can, just to start exploring new representations of the data. It’s also useful to start learning what sort of visual representations suit the data: some data just doesn’t make as much sense in a graph as a table, and that’s OK – but it’s good to find out now.

Because now isn’t the time to be shaving too many yaks, when it comes to visualisation libraries and tools, the ones that are fastest or that you are most familiar with are probably the best. For that reason, I like libraries that only touch the client-side such as the Google Charts API, or gRaphael (which I’ve been using to good effect recently). Interactive graphs, of the kind gRaphael makes trivial, are more than just eye candy: it’s actually really useful, with large datasets, to be able to mouse around a pie chart and find out which slice corresponds to which value.

Visualisation isn’t just a useful lens on the data for designers; it can be hugely beneficial for developers. A recent example of the usefulness of visualisation for development work in progress comes from this video behind the scenes on Naughty Dog’s PS3 game Uncharted 2: Among Thieves. About twenty seconds in, you can see this image:

of a developer playing the game with a vast amount of telemetry overlaid, reacting as he plays. It’s not pretty, but it does provide an immediate explanation of how gameplay affects the processors of the console, and is clearly an invaluable debugging tool.

What data exploration feels like

It often feels somewhat pressured: time is tight and whilst an hour spend going down the wrong alley is fine, a day spent fruitlessly is somewhat less practical. At the same time, without doing this exploration, you won’t even know what is “fruitless”. It can be frightening to feel so directionless, and overcoming that fear – trusting that any new information is the goal – is tough, but important to making progress.

It can also be overwhelming. Shownar ended up with a massive dataset; Ashdown’s is huge already. That dataset – its meaning, its structure – gets stuck in your head, and it’s easy to lose yourself to it. That often makes it harder to explain to others – you start talking in a different langauge – so it becomes critical to get it out of your head and onto screens.

It also feels lonely in the data-mines at times. Not because you’re the only person working on it, but because no-one else can speak the language you do; the deeper you get into the data, the harder you have to work to communicate it, and the quicker you forget how little anyone else on the project knows.

Invention becomes difficult: being bogged down in the mechanics of Making It Work often makes it hard for me to have creative ideas about what you can do with that data, or new ways of looking at it. Questions from others help – a few simple questions about the data opens enough avenues to keep me busy all day. One thing we tried to do was ensure that I made a “new graph” every day; the graph should only take about 30 minutes to write the code and do, but it ensures that I don’t spend all my time on writing processing or scraping code.

At times, the code you’re writing can feel a bit string and glue – not the robust, Quality Code you’d like to be writing as a developer. I’d like to TATFT, but this isn’t the place for it: we’re sculpting and carving at the moment, and the time for engineering is later. For now, getting it on the screen is key, and sometimes, that means sacrifices. You learn to live with it – but just make sure you write the tests for the final product.

There are a lot of pregnant pauses. For Ashdown, I’ve had long-running processes running overnight on Amazon EC2 servers. Until I come in the next day, I have no idea if it worked, and even if it did work, whether or not it’ll be useful. As such, the work is bursty – there’s code, and a pause to gather results, and then a flurry of code, and then more gathering. All I’ve learned to date is: that’s the rhythm of exploration, and you learn to deal with it.

What emerges at the end of this work?

For starters, a better understanding of the data available: what there is, how to represent it, what the core concepts are. Sometimes, core concepts are immediately obvious – it’s likely that “schools” are going to be a key object in Ashdown. Sometimes, they’re compound; the core concept in Shownar turned out to be “shows”, but how the notion of a ‘show’ was represented in the data turned out to be somewhat complex. As part of these core concepts, the beginnings of a vocabulary for the application emerge.

Technically, you’ve got the beginnings of a codebase and a schema, but much of that might be redundant or thrown out in future; you shouldn’t bet on this, but it’s a nice side effect. You also might, as a side effect of building a site, have the beginnings of some IA, but again, don’t bet on it: that’s something for designers to work on.

You should also have a useful tool for explaining the project to colleagues, stakeholders, and anyone coming onto the project new – and that tool will allow everyone else to gain insight into just what’s possible with the data available. Enabling creativity, providing a tool for non-developers to explore the data, is the key goal of such exploration. And that leads into a direction and brief for the final piece of software – and it’s a brief that you can be confident in, because it’s derived from exploration of the data, rather than speculation.

And then, the invention can begin.