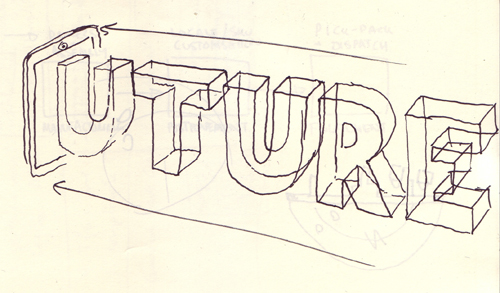

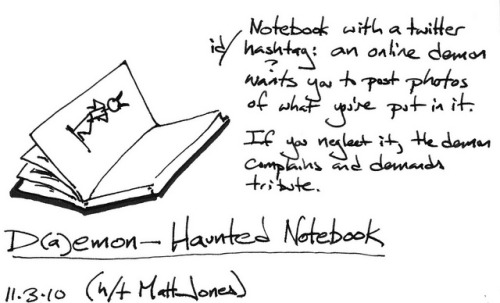

Josh DiMauro sent us this sketch of a “Demon-Haunted Notebook” (inspired by Matt J’s talk from last year’s Webstock conference). He explains:

The notebook would have a unique name and id, and a daemon would watch for “tribute” — online sharing of what you put in it.

The tough bit of implementation would seem to be defining a way to pay tribute, and to make it fun and easy, rather than onerous.

I liked “paying tribute” a lot. There’s more nice thinking and sketching over at Josh’s post.

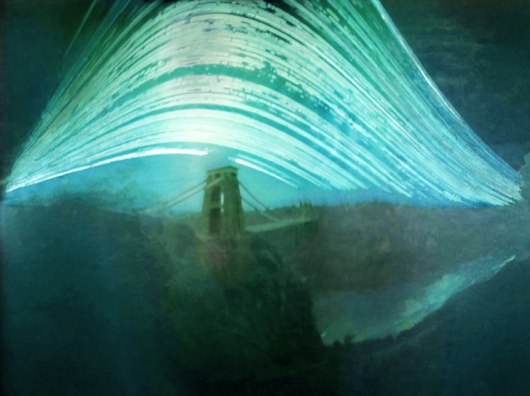

Via Kitsune Noir comes this pinhole photograph by Tim Franco, taken with a camera perched on a 7″ single. The film is exposed for the duration of the record. Beautiful.

On a similar note, Alex shared the above video. It’s a Red Raven Movie Record. There’s a series of images printed on the inner part of the record, and a mirror device that stands over the spindle. As the record plays, it provides its own soundtrack for the animation around the spindle.

Via Duncan Gough comes this lovely piece of paper product design: Muji’s Cardboard Binoculars.

This is Jonathan M. Guberman and Jim Munroe’s Automatypewriter. It’s a typewriter wired into a computer that you can (currently) play Zork on. The thing I like most – and what sets it apart from just being a typewriter turned into a teletype – is how the keys move when the machine is typing from itself. It turns it from being merely a printer, and into a ghostly writing-device. And, when used to play interactive fiction, makes it clear that the game being told is played out between both the player and the parser – writing the same text on the same device.

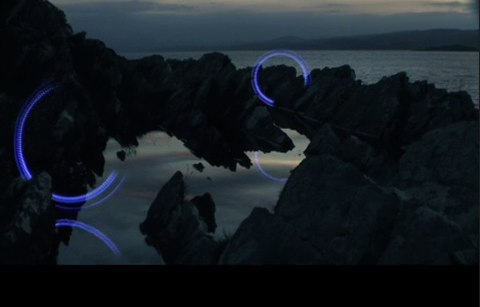

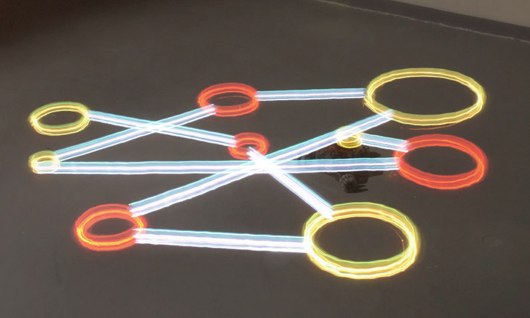

This is a part of a game of Artemis playing out. From the official website:

Artemis is a multiplayer game that lets you and your friends play as a starship bridge crew. One computer displays the main screen and runs the simulation server. The rest serve as bridge station consoles, like Helm, Comms, Weapons, Science, and Engineering.

In a nutshell: it simulates combat sequences from the Star Trek franchise. The captain doesn’t get a computer; instead, he has to tell everyone else in the room what to do. And so the captain’s role isn’t really part of the game mechanics at all; it’s a purely social role. The team are reliant on each other to display the appropriate screens on the main screen, execute decisions, and act on orders. And there’s nothing in the game stopping them from disagreeing or taking individual action.

The game is just some computation, network code, and a graphics engine; the real game plays out in the discussion between the crew and the decisions they make. Underneath the geeky exterior is a truly social game.