The RFID hacking workshop last week was both thoughtful and productive. I’m going to scoot through what we made and a few of the ideas, and leave any more detailed thoughts for other posts.

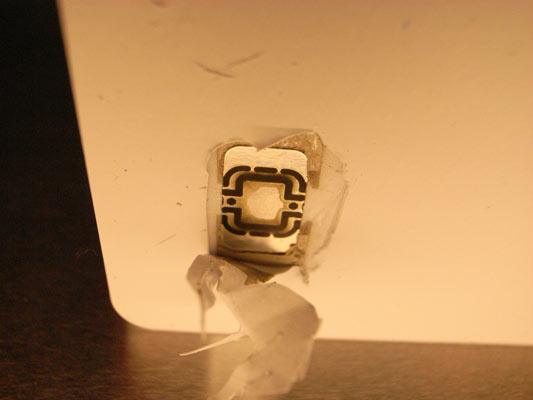

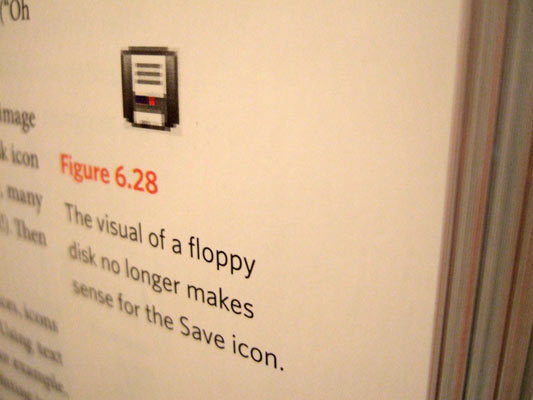

Day 1 was introductions and learning the technology. I’ve had a vague idea what RFID was before, but now Matt Karau told us all about it. So what is it? A powered RFID reader reads tags. An RFID tag is one of these:

Actually, that’s a smartcard together with an RFID tag–it’s from the inside of an Oyster card, the thing you use to pay on the London Underground. The antenna has broken off. RFID tags come in two flavours:

- Passive tags have an antenna and a small chip. The RFID reader sends a burst of power at the tag; the power runs through the antenna and powers the chip; the chip does something (maybe just loads an ID, or perhaps does a tiny calculation); the tag sends the data back to the reader and powers down. It might have a little memory too–perhaps 0.5-4Kb.

- Active tags are as passive ones, but with a battery.

Tags have large antenna loops, and are generally sealed inside a disk of plastic or paper. There are complexities, of course. RFID tags can be joined to sensors, so they report environmental data, or have more complex chips capable of running a tiny OS and cryptography applications, like the Oyster cards. There are different frequencies, different ranges you can hold the reader to invoke the tag, and different standards…

…but, essentially, the basic thing we’re using is a loop of wire that somehow reports the same number each time when you ring it with an electromagnetic field generated by the reader.

(Also on day 1 we had a go at calling the tags “spychips” instead of “RFIDs” every time we referred to them. The specific privacy fear isn’t a view I subscribe to, but it’s enlightening to see your new ideas being inflected by the language you use to reach them. I think it helped us see RFID as a technology in its own right, rather than relying on a single, badly-fitting metaphor.)

Day 2

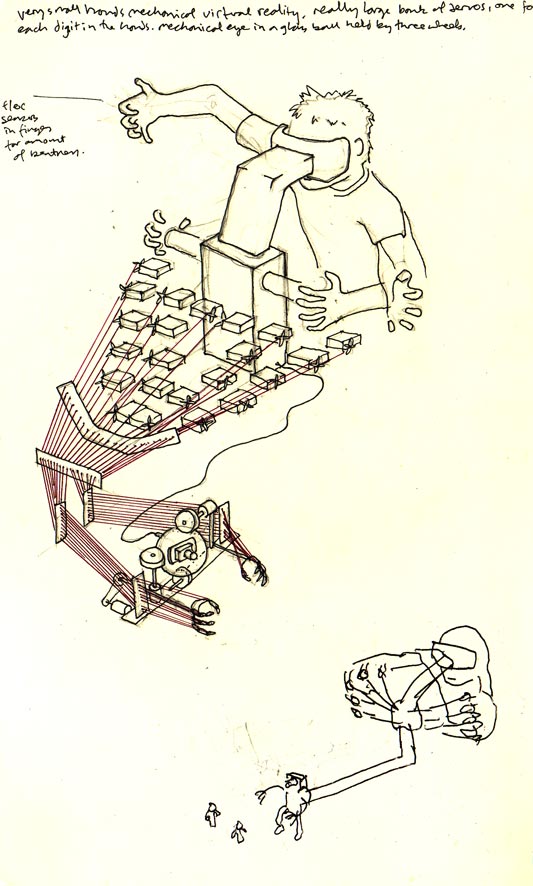

We started considering the range of RFID on the second day. These thoughts, about how to have interactions in a sphere of thin air a few inches around a hidden tag, led in part to last week’s post on RFID and forced intimacy. They also led to this:

(Thanks Timo for the photo.)

In the palm of each white glove (Jack and I both have one) is an RFID tag. Inside the white polystyrene box is an RFID reader hooked up to a microcontroller (on an Arduino board). The board is also hooked up to a vibrating motor.

When you put your hand near the block, it begins to rumble.

On my glove – I’m on the right of the photo – is a flex sensor, wired up to the controller. The more bent the sensor, the bigger the rumble of the box. So when you approach the reader with an open palm, there’s a gentle vibration. As you make a grabbing gesture, the vibration grows and the white box begins to lead about. It makes a fair racket.

Why do this?

Jack was keen on celebrating the magic of this kind of remote action. What if the vibrating motor was actually a toy car motor? You could approach a car, and push it with your glove, imbuing it with acceleration through empty air. By clenching your fist, it’d zoom faster! You’d have to chase it to keep it moving. With two gloves and two motors, you could control it too.

Are proximity and tensing the hand the correct interactions for these kind of toys? We can only think by making.

Day 3

We’d spent the second day trying to learn some of the intrinsic properties of RFID tags and readers. Some of the ones we discussed were:

- You can’t see the tags

- Tags are ways for machines to tell the difference between different lumps of plastic–heading towards what Matt Jones has called a robot-readable planet

- Knowing a tag’s ID is proof that the reader was geographically there, like the patterned card punches used in orienteering

- The functional bit is the reader, not the tag

This last point was a revelation to me. RFID interactions are not like button-pushing interactions. With buttons, the smarts are behind the buttons themselves. The buttons trip relays and activate switches. With RFIDs, the smarts are all in the thing you use to push the buttons.

Imagine a computer keyboard, but the keyboard isn’t plugged into anything. Instead, cameras in your fingertips read the letters on the keys, decipher them, and send those letters via a USB cable in your wrist to the computer. That’s more like RFIDs. With buttons, the button pusher is the fungible bit (any finger can be a poking device) and each button is special. With RFID, the button pusher needs to be clever.

Continuing this thought, imagine a keyboard which worked like this. You’d print out paper ones that were better for Quark or Photoshop or whatever. You’d draw ad hoc macro keys on the desk, in erasable pen. Taking this back to RFIDs, does their true potential only emerge when people can make and write their own copy-tags to fill their environments?

Anyway.

Since the reader is the functional bit, different tags can behave in different ways. Perhaps the reader could have a slot in the top, and that’s where you slip in a tag to state the kind of tool the reader is at the moment (a telephone, a camera, a query tool), and there are other kinds of tags that represent objects, like people, places and things. What about stacking tags, or having them interlock in different ways, or… or…

The possibilities multiplied.

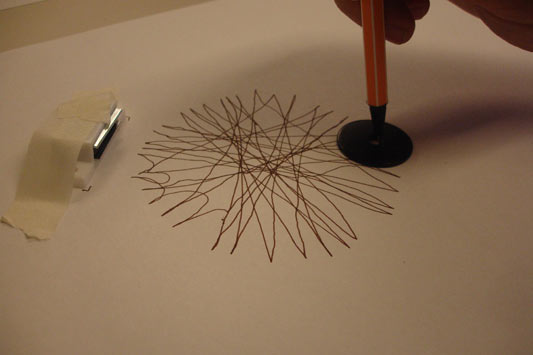

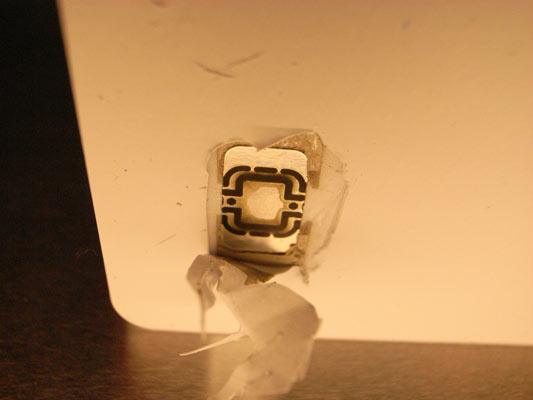

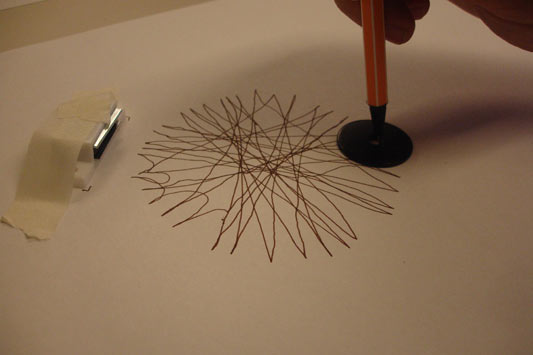

On the third day, we came back to where we’d started on the first day: Trying to get a feel for the field of an RFID reader.

Above is a drawing Timo made, with the RFID reader under a desk and a pen through a hole in the middle of an RFID tag. He drew only when the reader was picking up the tag ID. It’s a beautiful image. (Thanks Timo for the photo. This was when we were seeing if a magnet would distort the field. Other drawings didn’t have that in place.)

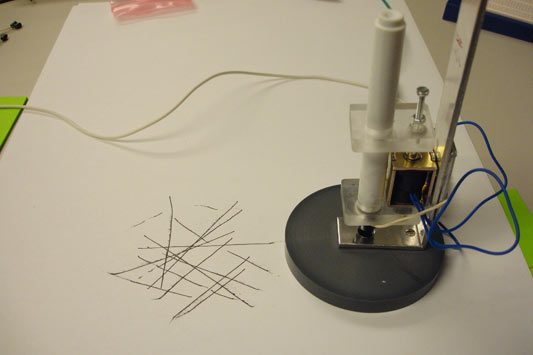

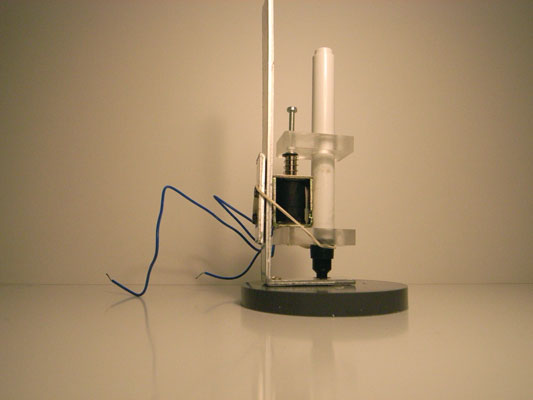

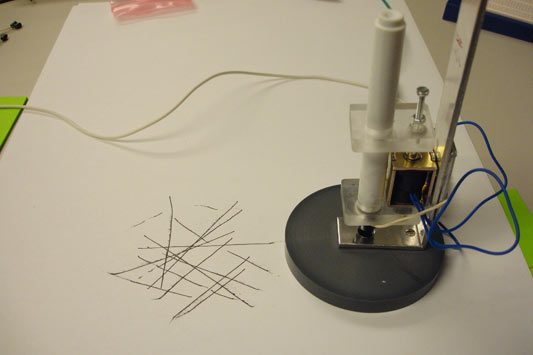

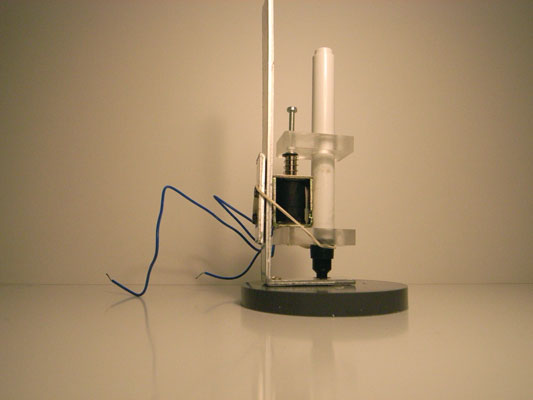

Jack and Timo spent time in the workshop at the Architecture School making a robot pen to do the same thing.

This pen has an embedded RFID tag (Timo’s photo again). It’s wired to the RFID reader, which controls a solenoid pushing the pen up and down. The pen is only down, and drawing, when it’s within range of the reader. You slide it around, and the automation does the rest.

The machine-aided drawings aren’t as beautiful as the totally hand-drawn ones, but ain’t that always the case.