My favourite trend spotters, trendwatching.com, just put out their monthly newsletter. (These are the folks who identified Generation C a couple years back, which let us finally express how the type of people you get on the Web are actually part of a much larger movement. Gen C comes up in the first few slides of most of our strategy work.)

This month’s trend is OFF=ON:

More and more, the offline world (a.k.a. the real world, meatspace or atom-arena) is adjusting to and mirroring the increasingly dominant online world, from tone of voice to product development to business processes to customer relationships.

Right on.

In the briefing, one of their example products is Availabot. Yes, that old thing. (Here’s a video of Availabot in action.) This is what they said:

Availabot is a golden oldie (it’s an ancient two years old!!), offering a physical representation of presence in instant messenger applications, which means Availabot plugs into your computer by USB, stands to attention when your chat buddy comes online, and falls down when they go away. Brilliant, and somehow very ON=OFF. But it apparently got stuck in concept mode. So could someone please bring this to market? (Just the waves of PR should make it worth the effort.)

It’s so true! Somebody should!

Okay, we should. And we’re going to. Oh, I’ve never said that in public before have I? There’s always a first time: yes, Availabot will make it to market.

Now seems as good a time as any to let you know what happened and what’s happening…

Ancient history

Way back in the mists of time (that is, 2006), Jack Schulze presented Availabot at the RCA show and picked up his MA. Schulze & Webb had just started, as a design studio and consultancy, and our first project was to make 100 prototypes and see where it took us.

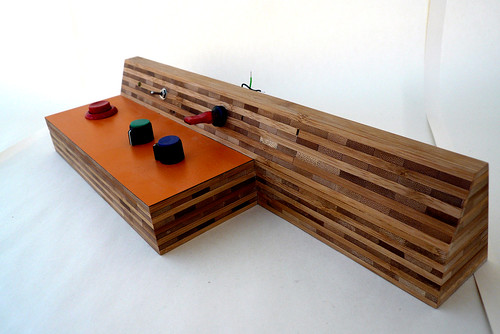

So we made a bunch and put them in a shop, as demonstration models:

But developing a product is expensive, and starting a consultancy takes a lot of biz dev and effect, so when [insert name of Very Large Toy Company here] saw Availabot, got excited and offered to buy an option, we happily accepted. It was supposed to be for 12 weeks. It dragged on for over a year… and then the option didn’t go anywhere. Ah.

A lot happened in the meantime!

- Availabot focus-grouped successfully. We know the best target market and how many they’d buy (and for how much).

- We learned the relative importance of customisation versus basic features and price (customisation is less important than we believed, and we’ve designed a way to inexpensively hit the mark).

- We had a patent application published: 2008/0122647.

- We figured out the ancillary businesses.

Oh, and we built a successful design studio (with projects such as Olinda), and a consultancy with clients including Nokia, BBC, Blyk, Ofcom and more, with a great network of designers and a newly established advisory group (and more of that in another post).

But when the option expired, we’d had enough of foot-dragging by [yes, that same Very Large Toy Company again] and we didn’t renew. Time passed… during which time we found new partners, and a new angle.

Going it alone

We recognise the growing Generation C (creation, social, connected people), and believe that the key future way to sell many modern, complex products, media and services is as physical things. It’s impossible to operate like this and not have a knowledge of China. And of course, we still wanted to take Availabot to market.

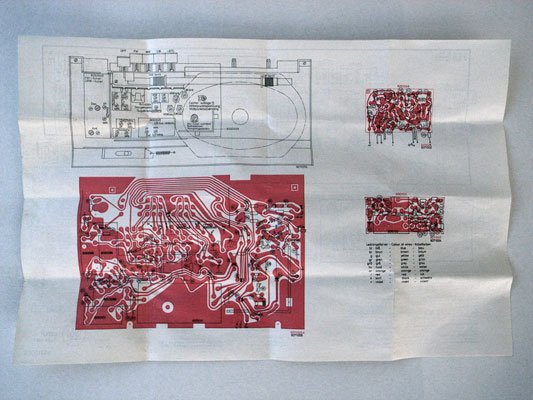

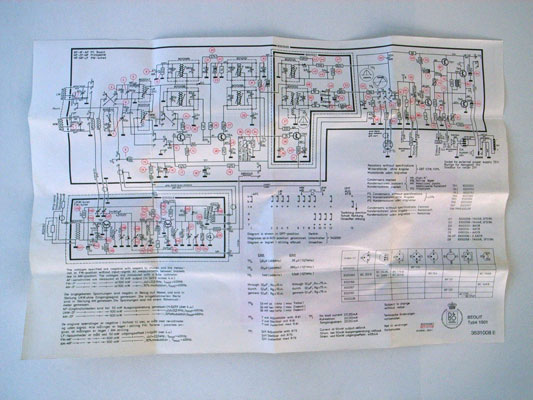

So we decided to treat Availabot as a world probe: it was decided that we would take Availabot through to the position of being factory ready, and in the process learn as much as possible about the processes of manufacture, and how to develop these kind of complex products with so many moving parts. (Availabot is unusual in that it requires mechanics, embedded electronics, desktop software which knits together lots of other bits of desktop software, and network features.)

And once factory ready prototypes were on the table, we would either go to market ourselves, or partner for either distribution or acquisition plus royalties. The economics of these models are sound.

Which brings us to the present day.

Availabot today

Availabot is almost ready.

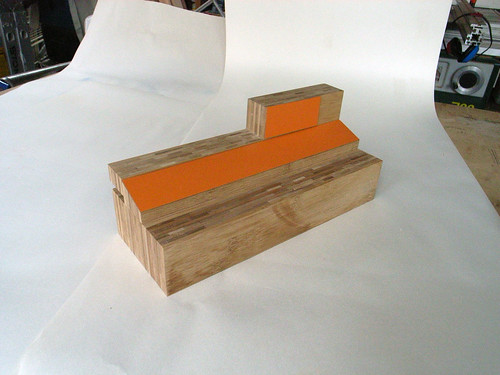

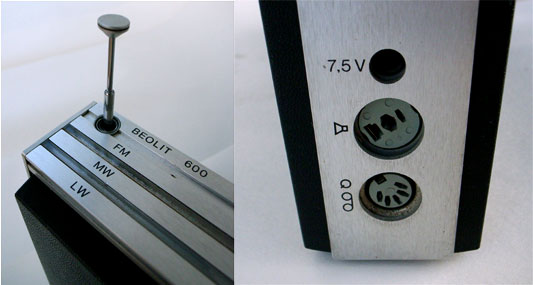

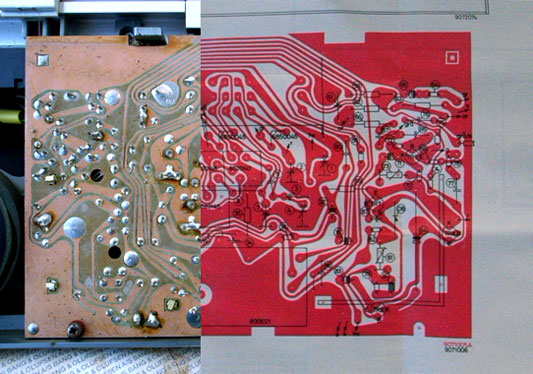

What you see above is a couple months old: a test model based on the original model, running on new circuitry with a novel mechanism that is as cheap as we can make it. We’ve been working hard with our electronics and manufacturing partner in Hong Kong to make this reliable, and to give it an open hardware API (over USB), which will of course be published.

The puppet in the picture is a placeholder. The new character development is almost complete. It looks pretty different, and I’m not going to show you photos of that, except to mention that although the customisation is toned down, we’ve come up with some exciting directions. Once the prototypes are finished, they’ll be attached to the newly improved motor and we’ll work on the liveliness of the movements. This is with our London partner and, though them, with visualisers and model makers working with our designs.

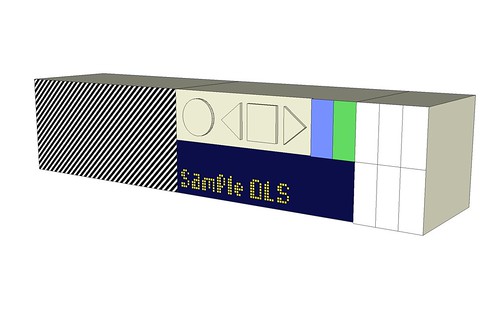

The team in Russia and Ukraine, working on the software, are a couple weeks away from finishing the second rev of the desktop software. Visually it’s pretty basic – the polished look comes when we go to market – but functionally it’s all there (there’s a plug-in API so third parties can hook Availabot up to all kinds of presence sources), and exactly what we need to demo the puppet round toy fairs.

And we have subsequent versions and associated businesses mapped out.

So what does factory ready mean?

Factory ready means when we decide to go to market, or we find a partner we’re happy with, there’s a direct path from here to mass production without any re-engineering. Bish bash bosh, in the shops.

Too long; didn’t read

Yeah okay, that was a lengthy story.

Here’s the summary:

- Availabot was stuck in a confidential options process with [Huge Toy Company] for ages. The work and market research was positive, but we didn’t renew. It’s a shame it didn’t work out.

- We’re working with partners and companies in London, Hong Kong and Russia to do character development (retaining some level of customisation), the mechanism, electronics, and embedded and desktop software. Future product directions are mapped out.

- Availabot is a very short way from being factory ready, at which point we’ll start showing the short run of prototypes to prospective partners and decide whether to go to market ourselves or let someone else take it on.

- We’re not ready to talk to partners until we have a twitchy bit of plastic on the table you can handle. But if you’re big enough, maybe it’s a good time to speak. Big means talking about taking over distribution and marketing globally, and working with us on a standard toy inventor and royalties basis (so I guess I’m talking Spin Master and up). If you’re talking about distribution or sales and you need a boxed product, or white labelling the technology, we’re not in a position to talk to you for a little while yet, sorry.

To be continued…

After so long having to keep quiet, it’s a relief to finally speak publicly. More news soon!

And of course, if you’d like help figuring out your OFF=ON product strategy, need design investigations or prototypes to reach an increasingly social and creative Generation C in the product, Web, mobile, media or services spaces, or can see another way our approach and skills can help your company, get in touch. S&W is over here, where technology is about people first.