If you asked me to pick the two cards Schulze & Webb play with abandon in the consultancy game, they’d be Product and Experience.

Products should be what toy companies call shelf-demonstrable–even sitting in a box in shop, a product can explain itself to the customer (or at least tell its simplest story in a matter of seconds). Organisationally, understanding a website or component of a mobile service as a product means being able to describe it in a single sentence, means understanding the audience, means focusing on a single thing well, means having ‘this is what we are here for’ as a mantra for the team, and it means being able to (formally or informally) have metrics and goals. Here’s it in a nutshell: You know it’s a product when it has an ethos–when the customers and the team know pretty much what the product would do in any given circumstance.

Then we play Experience. The experiential approach is how you and the product live together and interact. The atoms are cognitive (psychology and perception), while the day-to-day is it’s own world: Play, sociality, cultural resonance, and more. Each of these is an area of experience to be individual understood in terms of how it can be used. The third level of experience we deal with is context: How the product is approached (physically and mentally), and how it fits in with other products, people and expectations.

We can go a long way, and make decent recommendations of directions and concrete features, with those two cards.

And now we’re making a radio. As much as we’ve said these approaches apply across media, services and (physical, consumer) product, working with physical products has recently been only in our own research. Hey, until now. Until now!

Olinda is a digital radio prototype for the BBC

For the past month we’ve been working on the feasibility of Olinda, a DAB digital radio prototype for the BBC (for non-UK readers: DAB is the local digital radio standard, getting traction globally). That stage is almost over now – oh and yes, it’s feasible – so now’s a good time to talk.

Olinda puts three ideas into practice:

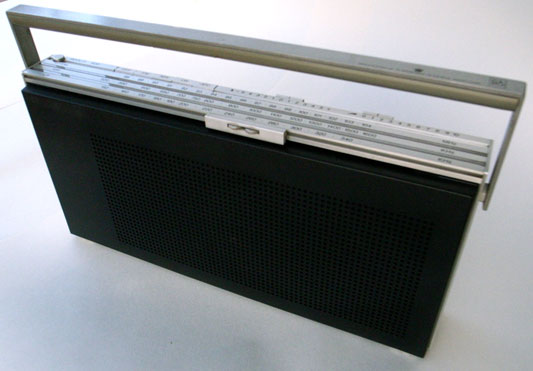

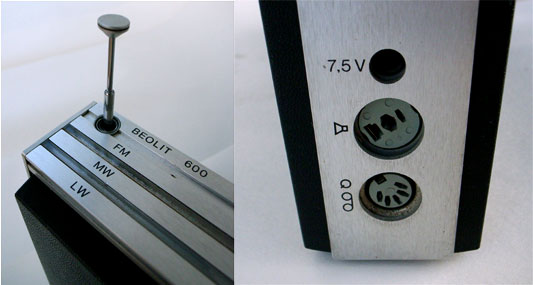

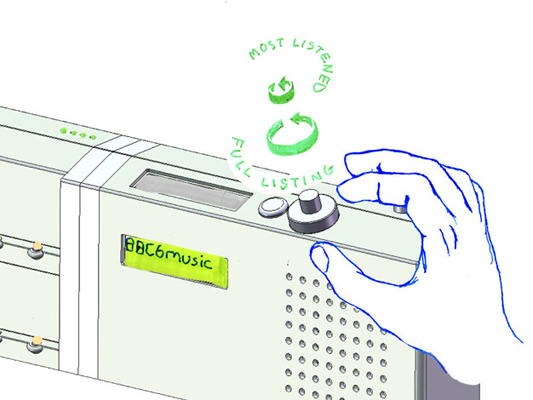

- Radios can look better than the regular ‘kitchen radio’ devices. Radios can have novel interfaces that make the whole life-cycle of listening easier. At short runs, wood is more economic as plastic, so we’re using a strong bamboo ply. And forget preset buttons: Olinda monitors your listening habits so switching between two stations is the simplest possible action, with no configuration step.

- This can be radio for the Facebook generation. Built-in wifi connects to the internet and uses a social ‘now listening’ site the BBC already have built. Now a small number of your friends are represented on the device: A light comes on, your friend is listening; press a button and you tune in to listen to the same programme.

- If an API works to make websites adaptive, participative with the developer community, and have more appropriate interfaces, a hardware API should work just as well. Modular hardware is achievable, so the friends functionality will be its own component operating through a documented, open, hardware API running over serial.

What Olinda isn’t is a far-future concept piece or a smoke-and-mirrors prototype. There’s no hidden Mac Mini–it’s a standalone, fully operational, social, digital radio.

The intention with Olinda is that it’s maximum 9 months out: It’s built around the same embedded DAB and wifi modules the manufacturers use. And it has to be immediately understandable and appealing for the mass market. Shelf-demonstrable is the way to go.

The BBC should be able to take it to industry partners, and for those partners to see it as free, ready-made R&D for the next product cycle. We have a communications strategy ready around this activity.

So that’s why I’m proud to say that, when complete, the BBC will put the IPR of Olinda under an attribution license–the equivalent of a BSD or Creative Commons Attribution. If a manufacturer or some person wants to make use of the ideas and design of the device, they’re free to do so without even checking with the BBC, so long as they put the BBC attribution and copyright for the IPR that’s been used on the bottom.

More later

The feasibility wraps up in the next week or so, as I budget the build phase. When build starts, we have an intern starting–perhaps two (yes, we got a great response to putting those feelers out). But that deserves its own post.

And there’s a lot to talk about. For start, what Olinda will look like (we have drawings and form experiments). And how the Product and Experience approaches will manifest.

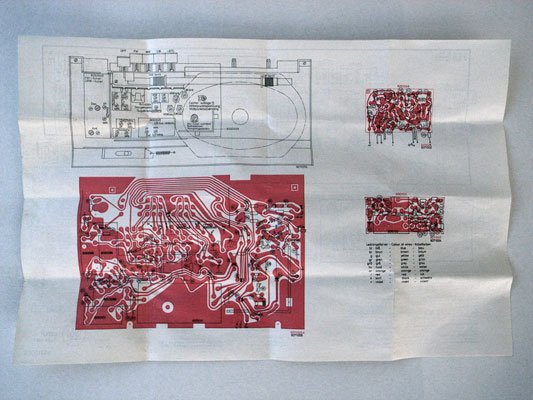

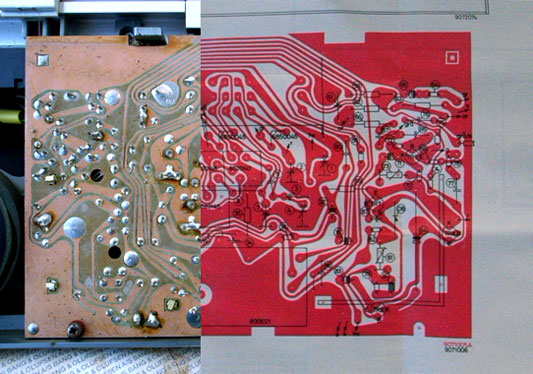

That’s for later. In the meantime, here’s the Frontier Silicon Venice 5 module operating on a breadboard:

The DAB module is wrapped in insulation tape, and you can make out the stereo socket (it’s blurry because it’s standing out of the focal plane) and the antenna. Running from the breadboard is a serial cable to my computer which is assembling and decoding messages for tuning, playing, receiving radio text messages and so on.

Thanks to Tristan Ferne, Amy Taylor and John Ousby and their teams at BBC Audio & Music Interactive for making this happen.

(Incidentally: Olinda, the name of this project, is aspirational, chosen from Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities (Olinda is transcribed at the bottom of that page). We could do worse that help along the radio industry in the same way Calvino’s city grows.)