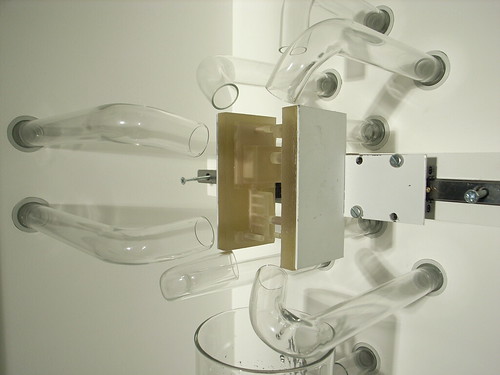

My favourite television ad at the moment is the Coca Cola one where the chap pushes his money into the vending machine and it triggers a sequence of magical adventures in a fantasy world, culminating in the fireworks-accompanied delivery of a cold bottle of Coke.

I like to think that all vending machines look like this inside. It’s a great way to make special the purchasing act.

Aside from product-specific events, like drinking for Coke, almost all our interactions with products are punctuated with moments like this: encountering, selecting, purchasing, showing off, selling. There are more. Each moment is an experience that good product design and advertising can make special, and use as a hook for brand communication. Each is a threshold at which, while the mere physical reality of the world doesn’t change, we’re taken us from one life to another–perhaps from being content with our lot to feeling covetous, or from not owning something to having it. These thresholds may appear small but they carry tremendous weight and meaning for us, are important in our individual and social lives, and are opportunities for design.

Some companies understand this very well. Apple make products that are legendarily pleasurable to unbox. The laptops have a charged battery from the get-go; the iPod box opens to reveal the device like a pearl. Unboxing is a weblog celebrating precisely this experience. Tiffany use high quality packaging to protect the jewels–but also because the glamour of passing over this ownership threshold reflects back on the glamour of the jewellery. (Tiffany have also clothed models in the packaging paper, which builds up the glamourous associations.) As a very different kind of business, Amazon understands that it’s not just about selling books. It’s about being present for customer for the duration of the life-cycle of the book, during browsing, discovering, learning about, wanting, purchasing, reviewing and finally selling on to someone else.

I think that discerning consumers – and we’re all more discerning now – delight in products when these acts are delightful, not because a product is like a cool big brother to us, or has a particular lifestyle we want to associate with.

Anyway, I like the Coke advert because it speaks directly to one of those acts, and also because it’s terribly pretty and vending machines are cool. Duncan’s TV Ad Land has more about Coke Happiness Factory and the team behind it (including a link to a large movie download), and you can watch the ad at YouTube.