This video got me thinking.

It’s footage of a simple Augmented Reality experiment from a programmer at British independent games developers Introversion, imagining what one element (the world map) of their strategy game Defcon might look like if there was an AR component to it.

I’m not as interested in the technical aspect of this experiment as I am the aesthetic.

I was struck by how well-suited the blue-on-blue, information-dense and highly representational display of Defcon is as an aesthetic for augmented reality. It helps to have a clear distinction between the real and the augmented. By making the augmented several degrees lower in fidelity than the real, it enhances the utility of the augmented elements. It creates seams between the real and the unreal, and helps the user process both real-world and AR information faster.

A few other things that struck me as being similar to this:

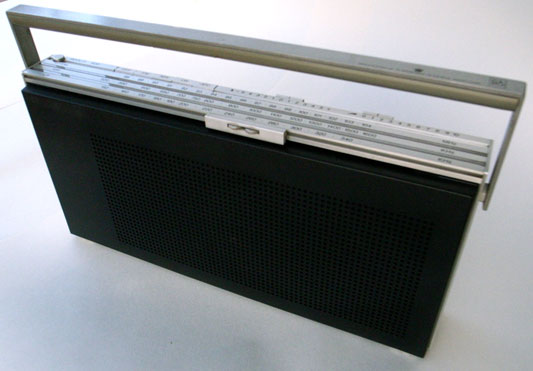

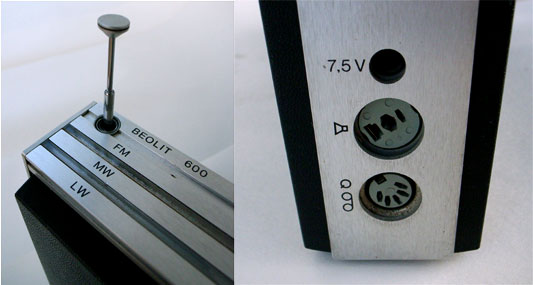

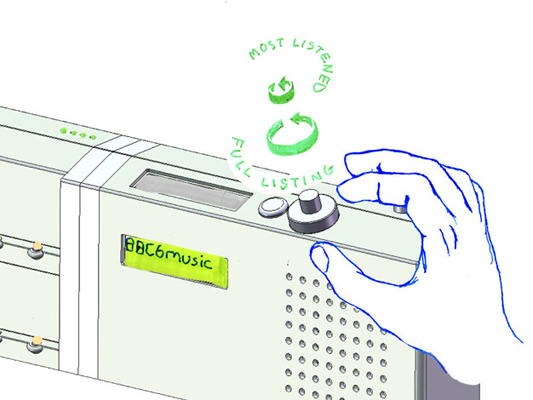

Jack spoke at This Happened in London last year about the Olinda project, and talked a little at the end about the form factor. Specifically: why it doesn’t look “prettier”. And he explains:

Each of the elements are trying to say what they do themselves in their own language.

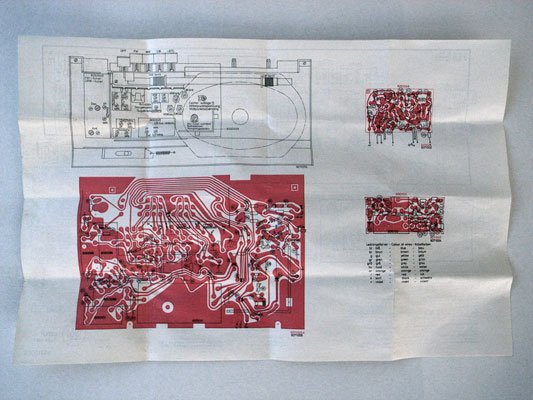

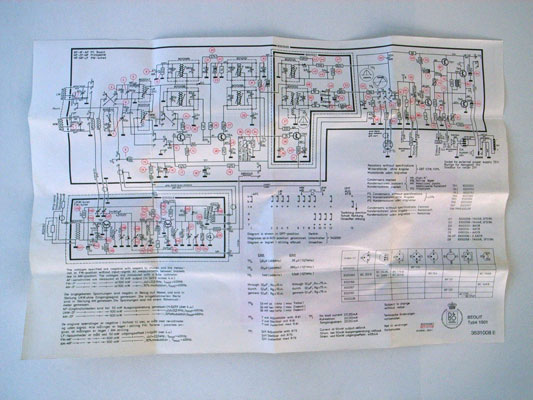

Matt has described this to me as “physical PowerPoint”. You instantly know from looking at this thing that it’s not necessarily finished yet; not quite complete. And rather than letting you down, that incompleteness (in this case, an aesthetic one) opens up a communication. It informs the observer that they can engage in a kind of dialogue with the radio, about what it is and what it does. Its form is not final, and that means that there is still space to explore and examine that form. A more finished project would shut out any such exploration from the user or observer, and simply impose its form on them; the only reactions left are accepting that form, denying it, or ignoring it.

Monospaced type that’s used for writing, not code. Most corporate communication takes on the same form: laser-printed, perhaps even letter-headed, smartly formatted documents, all of which look finished. But it’s so rare that the kind of documents we use in corporate communications are finished. More likely, they’re work in progress – either iterations of a report yet to be completed, reference materials for negotiations yet to be conducted, or as starting points for discussions that likely end on a completely different note. So why present them as concrete, unapproachable objects? By presenting the documents in barely-styled (yet thoughtfully laid out) monospace text, their role as intermediate objects becomes more obvious.

(Image from maxbraun, under a Creative Commons licence).

Rapid-prototyping plastic. The not-quite complete has not just look, but also feel, and as rapid-prototyping becomes more and more commonplace – and better understood by a wider audience – that unusual texture of fabbed plastic will quickly become another useful shorthand for “not a sketch, but not complete either”. This is a tactile shorthand that emphasises the boundaries between the world (of complete, final materials) and the work-in-progress.

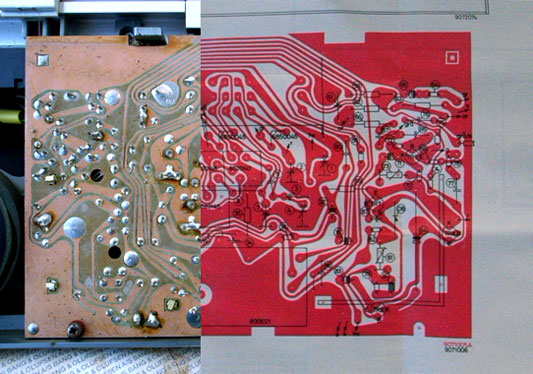

One technique that S&W has been using recently to illustrate design work is placing sketches or wireframes in situ. Whilst wireframes themselves are incomplete artefacts, designed to be work in progress, they still suffer for being uniformly incomplete. Wireframes themselves can be almost too beautiful, and this means that it becomes all-too-easy to criticise them as only wireframes, rather than as part of a product that exists in the world. Contextualising the sketches into the photograph places the design into the world. This enables the design to be understood within the world, and also (importantly) to highlight the seams between the unfinished design and the finished world around it.

How finished an artefact is is an important indicator of its relationship to the world: not just an indication of where it is in its lifecycle, but also one that explains how it should be understood, and that opens a dialogue between the observer and the artefact. It’s important that there is authenticity in the unfinished state. All the examples above are of things that are in a transition state between non-existant and final; they are not finished items that have then been distressed or made to appear cosmetically unfinished.

This is unlikely to be the last time I’ll write about this stuff on Pulse Laser; it feels like it has legs, and it’s something that I’m noticing more and more examples of. Given that, it only seems appropriate that this post remains