As a studio we have recently been quite pre-occupied with two themes. One is new systems of time and place in interactive experiences. The second is with the emerging ecology of new artificial eyes – “The Robot Readable World”. We’re interested in the markings and shapes that attract the attention of computer vision, connected eyes that see differently to us.

We recently met an idea which seems to combine both, and thought we’d talk about it today – as a ‘product sketch’ in video to start a conversation hopefully.

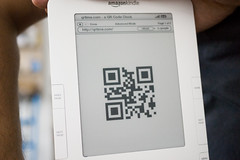

Our “Clock for Robots” is something from this coming robot-readable world. It acts as dynamic signage for computers. It is an object that signal both time and place to artificial eyes.

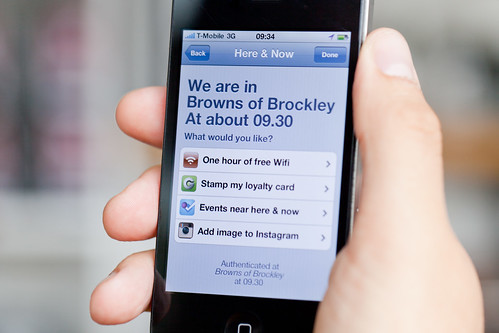

It is a sign in a public space displaying dynamic code that is both here and now. Connected devices in this space are looking for this code, so the space can broker authentication and communication more efficiently.

The difference between fixed signage and changing LED displays is well understood for humans, but hasn’t yet been expressed for computers as far as we know. You might think about those coded digital keyfobs that come with bank accounts, except this is for places, things and smartphones.

Timo says about this:

One of the things I find most interesting about this is how turning a static marking like a QR code into a dynamic piece of information somehow makes it seem more relevant. Less of a visual imposition on the environment and more part of a system. Better embedded in time and space.

In a way, our clock in the cafe is kind of like holding up today’s newspaper in pictures to prove it’s live. It is a very narrow, useful piece of data, which is relevant only because of context.

If you think about RFID technology, proximity is security, and touch is interaction. With our clocks, the line-of-sight is security and ‘seeing’ is the interaction.

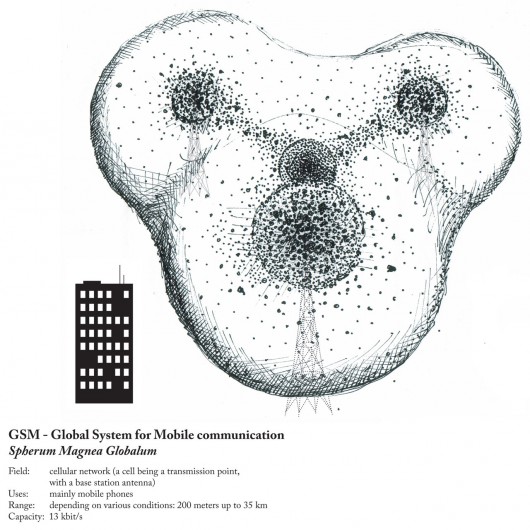

Our mobiles have changed our relationship to time and place. They have radio/GPS/wifi so we always know the time and we are never lost, but it is at wobbly, bubbly, and doesn’t have the same obvious edges we associate with places… it doesn’t happen at human scale.

^ “The bubbles of radio” by Ingeborg Marie Dehs Thomas

Line of sight to our clock now gives us a ‘trusted’ or ‘authenticated’ place. A human-legible sense of place is matched to what the phone ‘sees’. What if digital authentication/trust was achieved through more human scale systems?

Timo again:

In the film there is an app that looks at the world but doesn’t represent itself as a camera (very different from most barcode readers for instance, that are always about looking through the device’s camera). I’d like to see more exploration of computer vision that wasn’t about looking through a camera, but about our devices interpreting the world and relaying that back to us in simple ways.

We’re interested in this for a few different reasons.

Most obviously perhaps because of what it might open up for quick authentication for local services. Anything that might be helped by my phone declaring ‘I am definitely here and now’ e.g., as we’ve said – wifi access in a busy coffee shop, or authentication of coupons or special offers, or foursquare event check-ins.

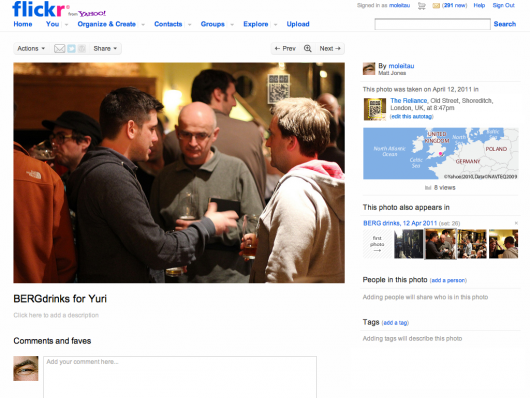

What if there were tagging bots searching photos for our clocks…

…a bit like the astrometry bot looking for constellations on Flickr?

But, there are lots directions this thinking could be taken in. We’re thinking about it being something of a building block for something bigger.

Spimes are an idea conceived by Bruce Sterling in his book “Shaping Things” where physical things are directly connected to metadata about their use and construction.

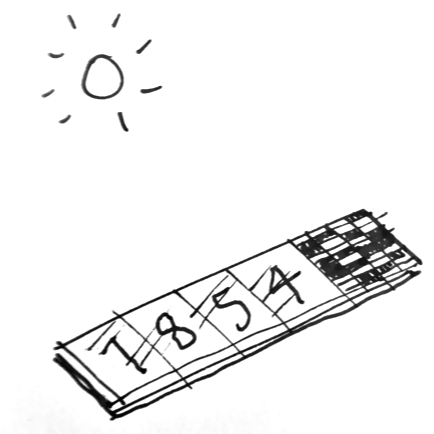

We’re curious as to what might happen if you start to use these dynamic signs for computer vision in connection with those ideas. For instance, what if you could make a tiny clock as a cheap solar powered e-ink sticker that you could buy in packs of ten, each with it’s own unique identity, that ticks away constantly. That’s all it does.

This could help make anything a bit more spime-y – a tiny bookmark of where your phone saw this thing in space and time.

Maybe even just out of the corner of it’s eye…

As I said – this is a product sketch – very much a speculation that asks questions rather than a finished, finalised thing.

We wanted to see whether we could make more of a sketch-like model, film it and publish it in a week – and put it on the blog as a stimulus to ourselves and hopefully others.

We’d love to know what thoughts it might spark – please do let us know.

Clocks for Robots has a lot of influences behind it – including but not limited to:

Josh DiMauro’s Paperbits

e.g. http://www.flickr.com/photos/jazzmasterson/3227130466/in/set-72157612986908546

http://metacarpal.net/blog/archives/2006/09/06/data-shadows-phones-labels-thinglinks-cameras-and-stuff/Mike Kuniavsky:

- http://www.orangecone.com/archives/2010/06/smart_things_ch_9.html

- http://www.ugotrade.com/2009/03/18/dematerializing-the-world-shadows-subscriptions-and-things-as-services-talking-with-mike-kuniavsky-at-etech-2009/

Bruce Sterling: Shaping Things

Tom Insam‘s herejustnow.com prototype and Aaron Straup Cope’s http://spacetimeid.appspot.com/, http://www.aaronland.info/weblog/2010/02/04/cheap/#spacetime

We made a quick-and-dirty mockup with a kindle and http://qrtime.com