I mentioned the John’s Phone on the studio mailing list last week. We ended up getting one to look at in the studio; it arrived this week, and I spent some time exploring it.

The John’s Phone is a simple mobile phone made by Dutch design firm John Doe. The phone came about as an attempt to take the ultra-simplicity of their From The Supermarket to a mobile phone. To quote their blogpost on the subject:

We’ve always wondered why most affordable phone looks so dull and boring. All cell phones are great high-tech product we like to use every day. Why not spend more time in designing. It’s the things we don’t see that are the most essential to creating a great design. A great design is a present. Why not make yourself happy with a present everyday in your pocket.

It’s a really immediate product: the entire front face is devoted to the keypad and physical interface. The top of the phone has an LCD display, positioned much like an old-fashioned pager; the side of the phone, which you can just see in the pictures above, has a rocker switch for volume, a SIM card slot, a switch for the ringer volume, and a power switch.

The phone makes its intention clear: the immediacy of use and that interface is more important to it than any screen or display-based interaction. It’s all about phone calls and phone numbers.

The John’s Phone is almost exactly the same size as an iPhone 4 – but its keypad takes up as much space as the touch screen does on the iPhone. The touchscreen has become a focal point of the design of smartphones, the hardware being designed around that bright rectangle. The John’s Phone is equally designed around its interface (or, at least, the “input” element of that interface) – it just happens to be a physical keypad.

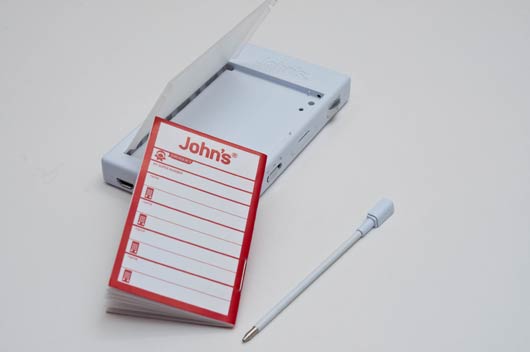

There are delightful, surprising touches. There’s a biro hidden down the side, where you might expect a stylus on an old touchscreen phone. You can use it to write in the addressbook hidden in the back of the phone.

But that paper addressbook sums up some of the problems with a phone this simple. Is that simplicity for the purpose of simplification, or to support an aesthetic of simplicity?

The website for the phone claims that it’s “the world’s simplest cellphone“. That’s true – if you agree with their idea of what a cellphone is.

For instance, if you believe text messaging to be a fundamental feature of a cellphone, then the John’s Phone doesn’t even live up to your expectations of what a mobile phone is. But if all you want your mobile phone to do nothing but send and receive calls – which is true of many phone owners – then it really is a simple, satisfying expression of that goal. Satisfaction with the device comes down to what your expectations – or requirements of it – are when you first pick it up.

That aesthetic of simplicity is at times complicated by the technology the phone runs on. Whilst John Doe promote the paper addressbook as the best way to store your phone numbers, reading the manual reveals that there is a ten-number memory built into the phone.

How do you put numbers into that memory? By typing **1*01234567890# (to put “01234 567890″ into slot “1”).

Doesn’t that, as an interface, feel totally at odds with the aesthetic the physical device is cultivating?

(Of course, “reading the manual” seems like an activity also at odds with a device already so explicit in its physical form; had I not done so, I’d have been perfectly happy not knowing about that feature.)

At first, the character-design on the “hello” and “goodbye” buttons seems at odds with the restrained, minimal physical exterior.

As you use the phone, though, you’ll get to see a lot more of that character. He’s called Fony, and he appears throughout the phone’s operation. He’ll wave hello and goodbye to you when you turn the phone on and off.

When the phone’s asleep, you might see him tucked up in bed.

When you charge the phone, he gets electrocuted from time to time (which seems curel to a character I’d imagine I was supposed to be sympathetic towards).

I can appreciate the care and attention in the realisation of Fony. He’s charming and never intrusive on the phone’s screen, often explaining what the phone’s currently doing through his appearance (rather than through text, which there’s very little space for). John Doe say (in their explanation of his design) that “Fony makes John’s a friendly phone“. I think he’s part of that friendliness – but not nearly as much as the much more immediate friendliness of the clear, simply designed hardware.

It’s important to factor the price of the product into any discussion of it. The John’s Phone costs €70 – about £50. That puts it in line with fairly cheap pay-as-you-go phones. (And: the John’s Phone is sold unlocked from any carrier, so that’s £50 without any carrier-subsidy).

Price changes the the relationship to a product. At £150, this would be a premium product designed for a wealthy few as a provocative statement – but likely a “second phone”.

At the current price, it’s a much more relevant purchase for a wider audience. If that price were even lower, new – and larger – audiences become available.

It’s only fair, in the end, to criticise the John’s Phone in light of that initial quotation from John Doe, which serves as a kind of design brief:

A great design is a present. Why not make yourself happy with a present everyday in your pocket.

A device that makes you happy; a device that is a delight every time you pick it up. By those criteria, the John’s Phone is clearly a success. Everyone who’s seen ours wants to pick it up and take a look; everyone who picks it up smiles, and plays with it, explores its secrets; everyone wants to answer the question “is it really a phone”?

Yes, it is. And it’s not just an ultra-simple phone; it’s an affordable ultra-simple phone, that you can buy right now. All credit to John Doe for taking their vision of what a mobile phone could be, and making it real, at the right price.

Another open-source product making its debut in hardware is the OpenOffice.org Mouse (pictured left). Eighteen buttons, an analogue joystick… I admit to sucking my teeth in disbelief when I first saw it; the comparisons that have been made to

Another open-source product making its debut in hardware is the OpenOffice.org Mouse (pictured left). Eighteen buttons, an analogue joystick… I admit to sucking my teeth in disbelief when I first saw it; the comparisons that have been made to