Update, February 2013: Howmanyreally.com has now finished its prototype trial, and is no longer live.

About two years ago, we started work with

Max Gadney on a series of workshops looking at how digital media could be used for relating stories and facts from both history and current affairs.

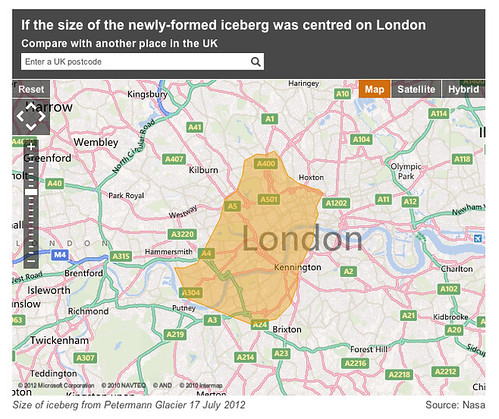

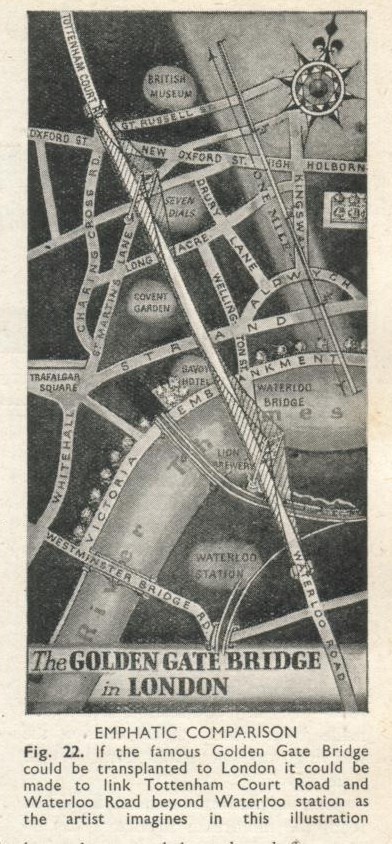

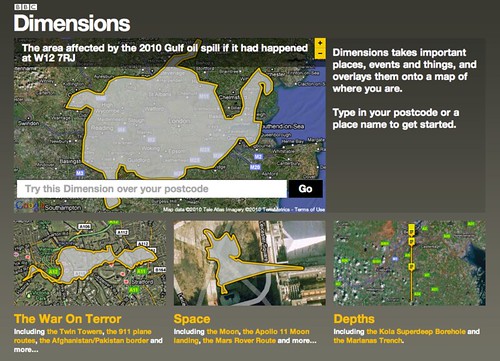

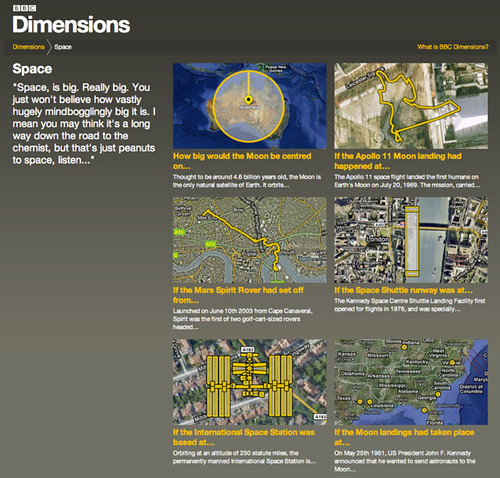

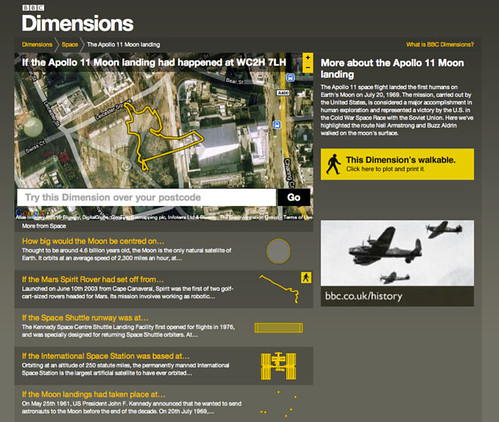

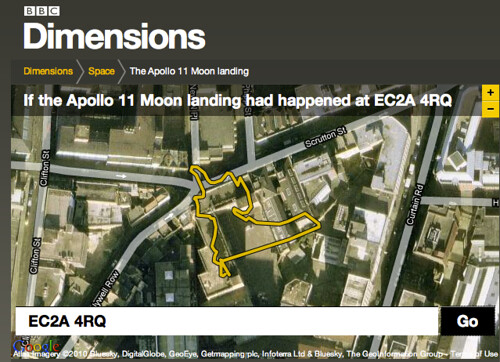

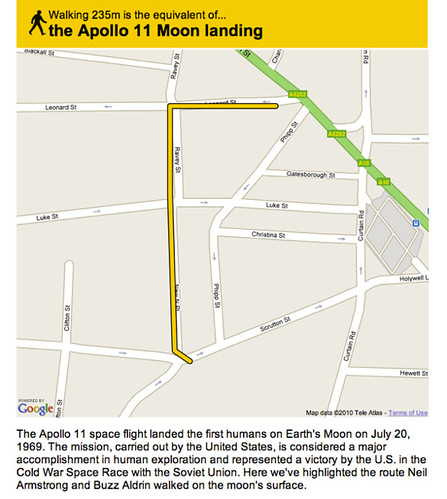

One of the concepts was called ‘Dimensions’ – a set of tools that looked to juxtapose the size of things from history and the news with things you are familiar with – bringing them home to you.

About a year ago, we launched the first public prototype from that thinking, http://howbigreally.com, which overlaid the physical dimensions of news events such as the 2010 Pakistan Floods, or historic events such as the Apollo 11 moonwalks on where you lived or somewhere you were familiar with.

It was a simple idea that proved pretty effective, with over half-a-million visitors in the past year, and a place in the MoMA Talk To Me exhibition.

Today, we’re launching its sibling, howmanyreally.com

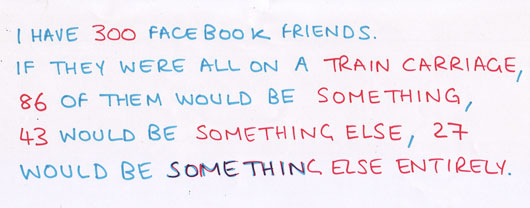

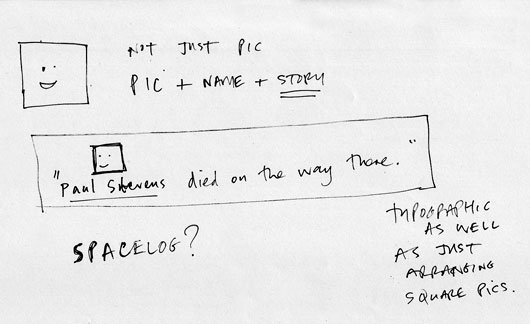

You can probably guess what it does from the URL – it compares the numbers of people who experienced an event with a number you can relate to: the size of your social network.

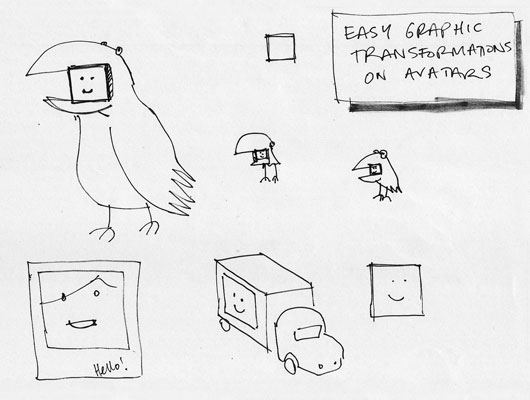

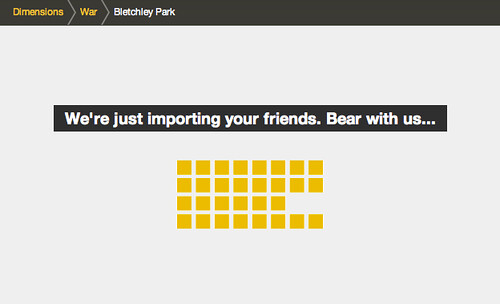

For example, the number of people who worked at Bletchley Park cracking codes and ushering in the computer age…

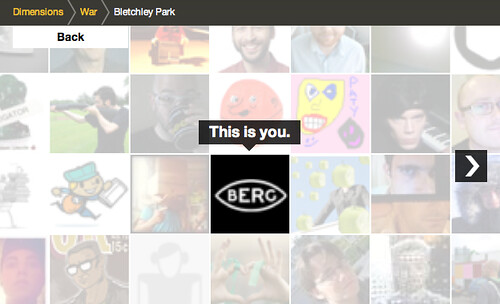

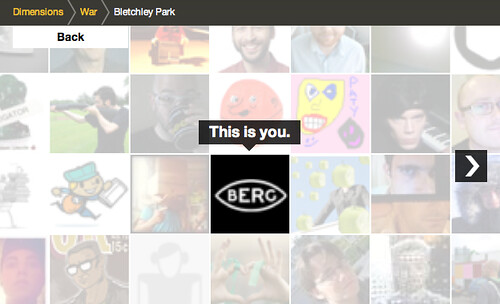

I can sign in with my Twitter account

and I’m placed at the centre…

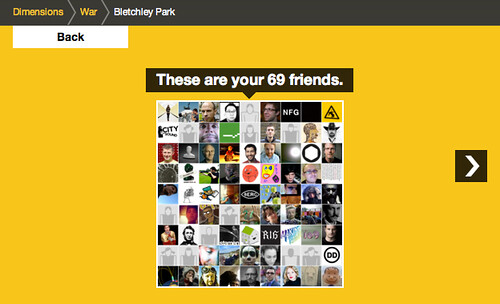

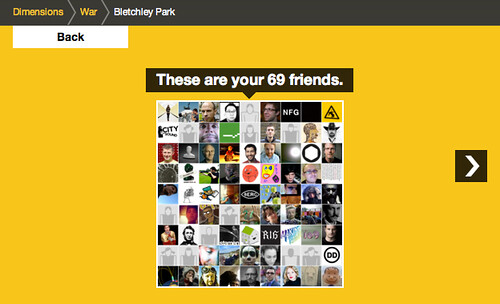

Clicking to zoom out shows me in relation to those I follow on Twitter…

Zooming out again places that group in relation to those working at Bletchley Park in 1945.

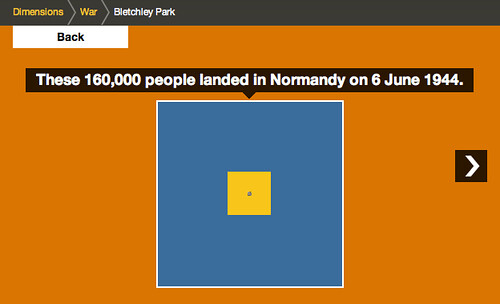

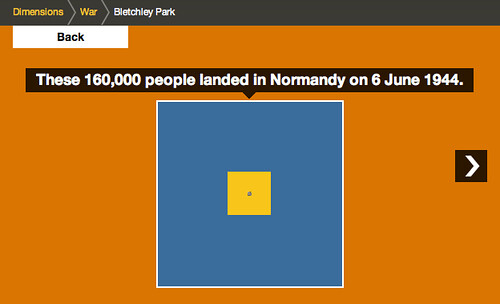

Which, in turn, is then compared to the Normandy Landings

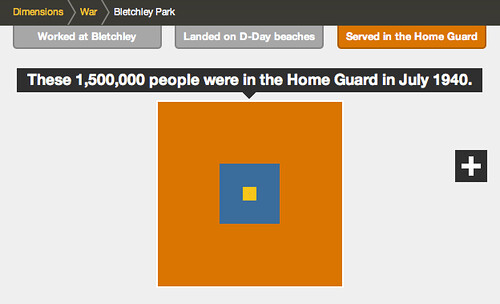

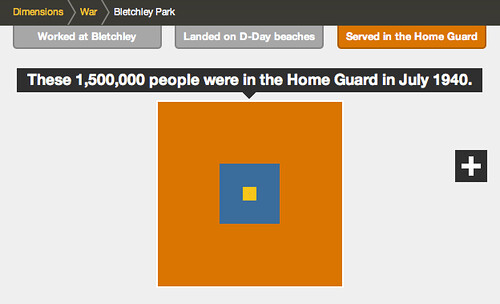

…and finally the 1.5m people in the Home Guard

Despite the difference between the size of the final group and your social network, it can still just be made out at the centre of the diagram, helping us imagine the size of the group involved in these efforts during World War 2.

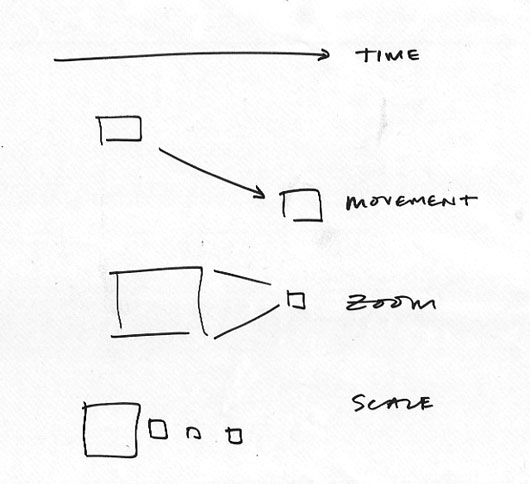

Of course this visualisation owes much to the pioneering work of the Office of Charles & Ray Eames – particularly their “Powers of 10” exploration of relative scale, which is a shared source of inspiration in the studio.

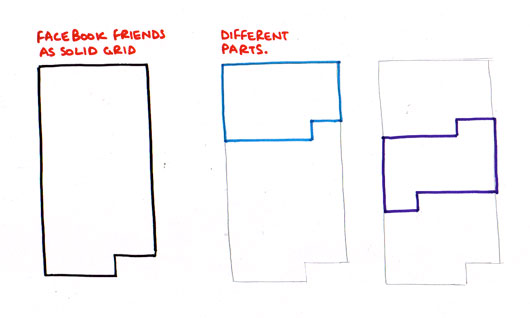

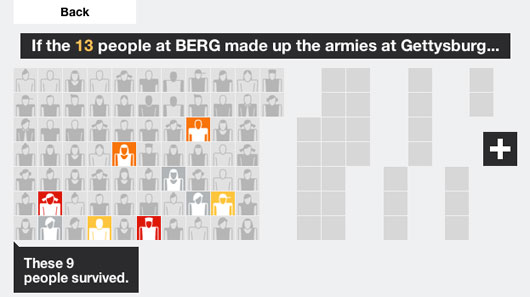

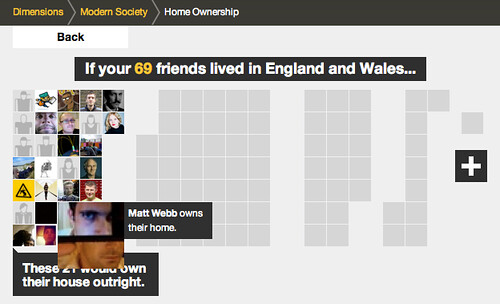

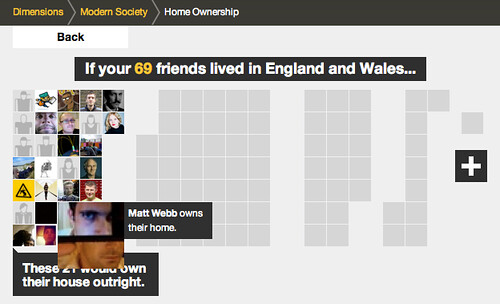

There is another type of comparison featured in the prototype – one which during development we likened to an assembly in a school playground – where your friends are gathered into different groups.

For example, this one looks at home ownership in England and Wales:

Starting again from your twitter network…

This visualisation starts to arrange your social network in groups…

relating to the different experiences…

and you can also rollover the individual avatars in this version, to see the individual’s experience…

All the ‘dimensions’ in howmanyreally.com allow you to post what you’ve discovered to your social networks, if you want…

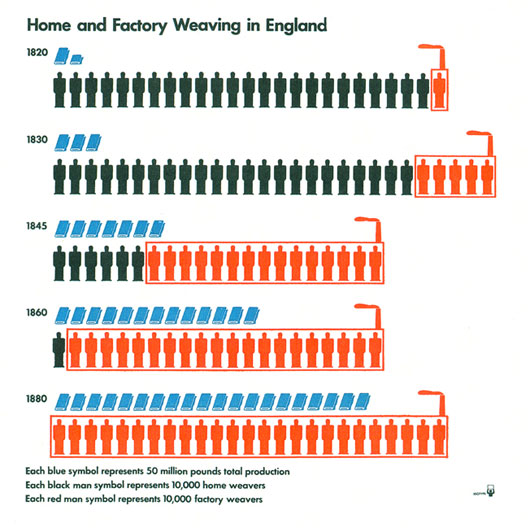

There are a lot of influences on howmanyreally – both from the Eames, and in the case above – the work of Isotype, which I hope we’ll go into in a further post.

But for now let me encourage you to explore howmanyreally.com yourself. It’s little bit of a different animal from its sibling IMHO, which had such an immediate visual punch. This is a slower burn, but in my experience playing with it, I’ve found it can be just as powerful.

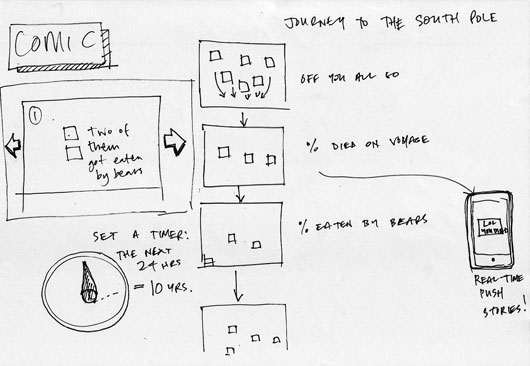

Both human history and current affairs unfortunately feature an high percentage of turmoil and tragedy.

While I’ve selected some rather neutral examples here, juxtaposing your friends with numbers of those injured, enslaved or killed through events in the past can really give one pause.

In its way, I’ve found howmanyreally.com a tool for reflection on history. A small piece that I can loosely join to a larger exploration of the facts. I really hope that’s your experience too.

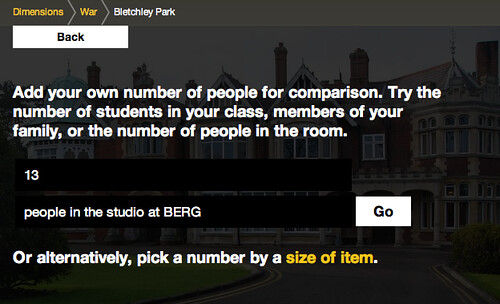

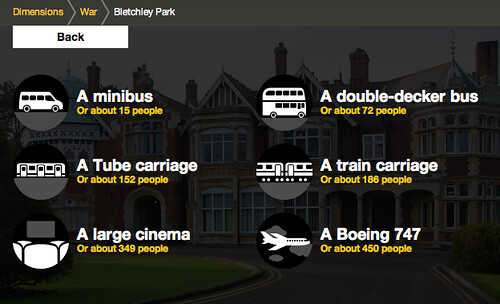

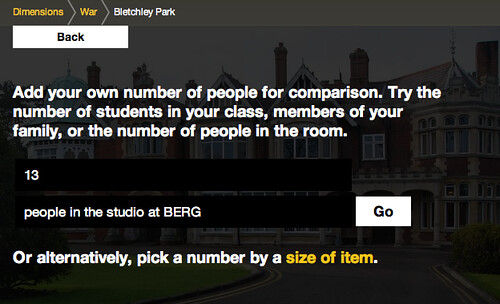

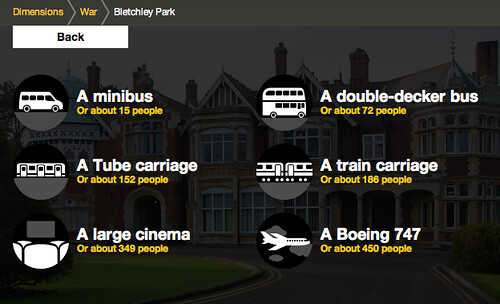

If you don’t wish to use your social network accounts in connection with howmanyreally, you can enter a number you’re familiar with to centre the comparison on – for instance the size of a school class, or those in your office perhaps.

Or you can choose one of the comparisons we’ve prepared – for instance the number of people typically in a large cinema…

As with howbigreally.com – if the prototype is successful, these new visualisations are designed to be incorporated as an element within the bbc.co.uk history and news sites. So do give your feedback to the BBC team through the contact details on the site.

It’s just left to me to say thanks to the team at the BBC who originally commissioned these explorations into history at human scale, including Lisa Sargood, Chris Sizemore, and Max Gadney.

Howmanyreally (and Dimensions as a whole) has been a fascinating and rewarding piece to work on, and thanks many members of the studio who have made it happen: Nick Ludlam, Simon Pearson, Matt Webb, Denise Wilton – and the core team behind its genesis, design and development: Alex Jarvis, James Darling, Peter Harmer and Tom Stuart.