“I’d describe myself as an inventive, but bad, prototyping engineer; I’ve got a shallow knowledge of most fabrication processes”

One of the things Jack has a shallow knowledge of is bookbinding. This morning, he’s talking to me about some interesting notebooks he’s been making, and about a product – and service – that could emerge from his explorations into this craft. Jack shows me a selection of books in various stages of completion. The process of manufacture, especially at the one-off scale he manufactures them, is relatively simple, and worth explaining, as it’s critical to his subsequent explorations into product.

You start with the paper, and the insides. Your paper stock is folded over to create several sections of the appropriate size and thickness. Once these have all been created, they’re stitched along their spine to hold the section together, and cut (usually with a guillotine) to the same thickness. This isn’t the primary way the spine holds together; it’s more of a convenience. Then, the sections are glued together, with a three thin strips of tape extending horizontally over the first and large page, and a thick scrim wrapping their outer edges. Finally, a thin piece of paper is strongly glued over the spine, and it’s this glue that holds the spine together.

All that remains is to add the cover – two pieces of card for the front and back, and a third thin one for the spine, along with endpapers and a cloth covering. The book is not made to fit its cover – the cover is cut to match the paper size, however that has turned out. The end result is almost exactly like any hardback book you’d find for sale today.

Why make your own notebooks, though? What’s wrong with the ones on the shop shelves?

Designing books around needs rather than form-factor

One reason to make your own book is to meet needs that existing books cannot. In Jack’s case, this is all about the paper – or, rather, how the paper reacts to different kinds of writing implement. Whilst a fairly traditional, smooth paper stock makes sense for writing notes in ballpoint, or sketching with pencil, Jack also likes to work with a thick brush pen, and a much thicker, rougher stock suits this better.

(I tend to approach purchasing notebooks by thinking about form-factor first, and considering the paper second. When you’re making your own, it’s much easier to reverse that thought-process and think about the paper first – and, based on my own experience of notebooks, that’s likely to lead to much greater satisfaction with the end product.)

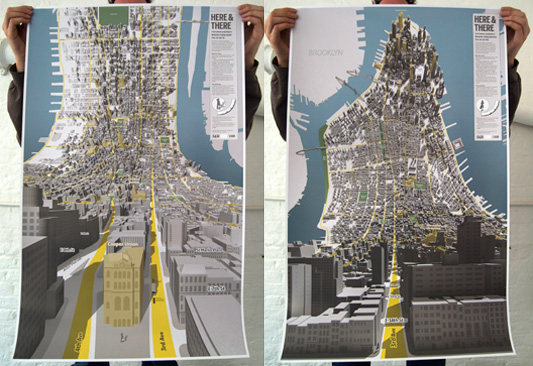

Given that Jack likes to both write and draw in his sketchbooks, why not make a book that includes both paper types? He shows me a book without a cover. The uncovered book has three paper stocks in it: a regular, smooth stock at the front for writing notes; a thick, rough stock at the back for brushwork; and, in the middle, larger pieces of paper that are folded in. Some of these unfold into a roughly A3-sized piece of paper; one, in the center, unfolds into a giant panorama for illustrating skylines.

The three stocks are built up and then bound together into a cover. This immediately demonstrated something else that Jack learned from the uncovered book: whilst the three sections were equally sized in terms of page count, they really should have been equal in thickness: because the paper stocks are all of different thicknesses, the book ends up being slightly lopsided.

There were two other notable problems with this book: firstly, that because of the different kinds of work that occur in each section, Jack was more likely to use up one section faster than another, and secondly, that it still ends.

The next experiments were about building a book that wouldn’t end.

Making a re-usable sketchbook

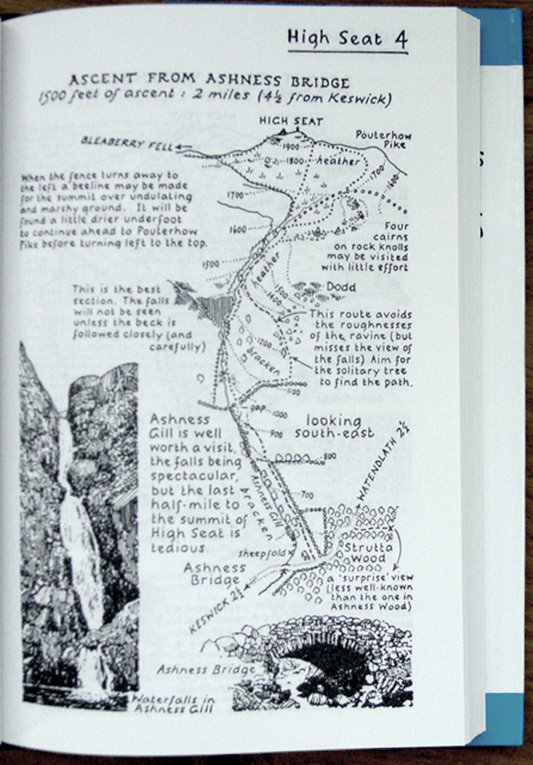

The next notebook Jack shows me is made of nine sections of pages, bound into three bound clusters – like three little sketchbook inners. These are bound together into a book, but not in a traditional manner; instead, the piece of scrim at the end of the section “overlaps” and sticks up into the pages, clearly indicating the end of a section. The scrim makes the binding process obvious to the book’s owner, and it’s the binding process – and the user’s visibility of it – that allows the idea of a service to form around this product.

Jack explains his notion of the service: it’s a way to preserve the contents of your notebook as an archive, whilst keeping the book in use as an ongoing tool. When you get to the second fold of scrim, you should find a note telling you it’s time to send the book off to be dismantled. This needs to be a really fast process for the service to work well – overnight, ideally; whilst your notebook is away, you won’t be able to take notes, so we need to make sure it can be returned to you as fast as you can. Fortunately, rebinding the book is a very, very quick process, especially for a skilled binder. It is, after all, just glue.

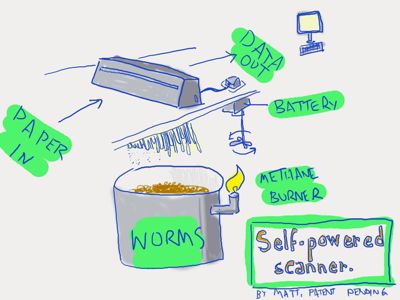

The service cuts out the sections from your book, and rebinds it with new sections. It also scans all the pages that have been removed and uploads them to a Flickr-like service. This is definitely a secondary characteristic of the service, and not the primary goal; however, so many notebooks are destined to be scanned, it seems sensible to offer it, and it helps act as another kind of archival, more akin to backup. The service then returns the freshly bound book, and the archived sections, to the sender.

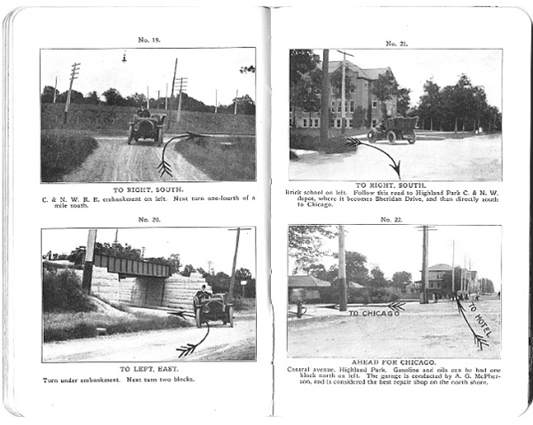

There’s nothing to force us stopping at just binding pages in. The service could also bind in content printed on demand – upcoming trips from Dopplr, editorial content, short fiction, favourite photographs from Flickr. The notebook becomes genuinely personalised for the owner. I note that the service paradigm makes it possible to know quite accurately how much on-demand content to provide – the more frequently a notebook owner sends their book in, the shorter the timeframe the Dopplr page should cover, for instance.

When Jack suggested the notion of editorial content he asked “what if Monocle had a sketchbook at the back?” I thought back to Rod McLaren observing that the stock Monocle is printed on is particularly apt for drawing on:

What if we reverse that idea: make the a notebook, printed on beautiful stock, with sixteen pages of Monocle at the back? Given such a service is likely to be subscription-based, what better model to use than one of publishing a magazine – except it’s a customised magazine, built especially for you, and largely blank pages?

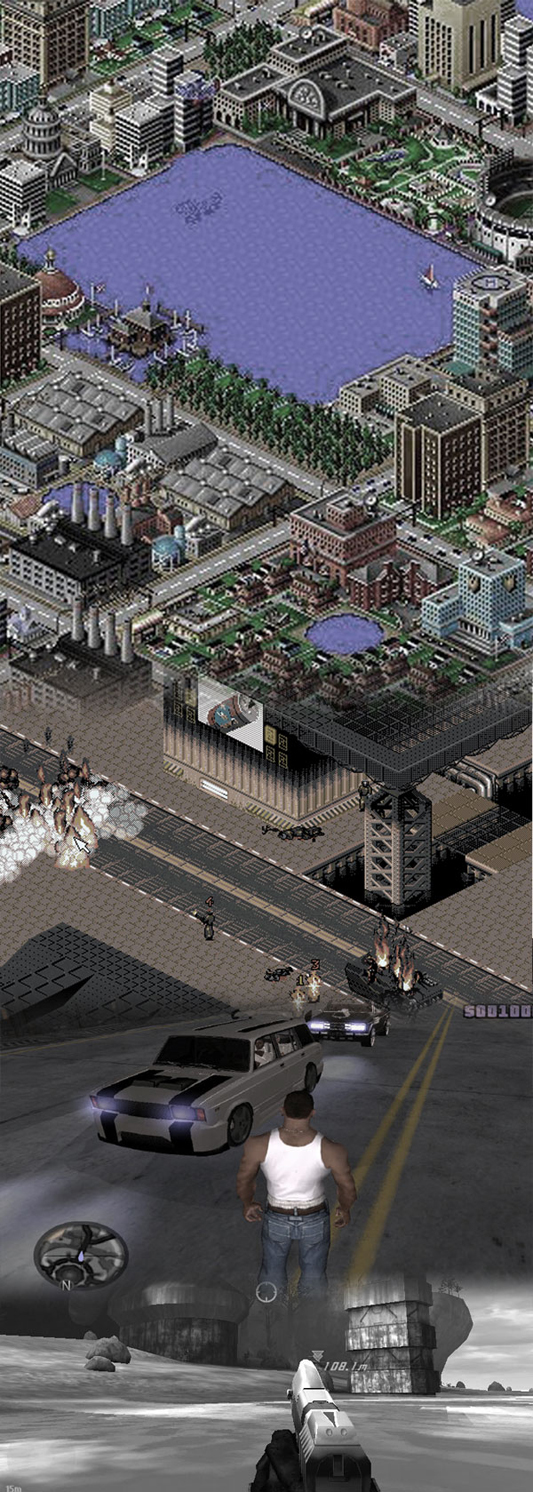

And this, of course, matches the way we work: a small amount of work in progress, ongoing, imperfect; the rest archived off for reference and posterity. There’s still value in that remainder, but it’s not worth carrying around everywhere with you. The notebook remains of relevance in the present; the separated, archived sections become archival content. This reminds me a lot of Hedeigger: the current notebook, in your hands, is Zuhanden, “ready-to-hand”, a practical concern; the archival sections are Vorhanden, “present-at-hand”, reified information.

I’ve seen other forms of endless notebooks on shop shelves, recently. They have a fold like an envelope on the back cover, and when you reach the end of one book, you tuck the cover of the next into it and keep going. Of course, this eventually becomes unwieldy, but it’s a far simpler solution to a notebook running out.

Jack’s product, however, engages a little more with the notion of bookhood in the notebook: that the book should only be the things of immediate concern, and there needs to be an important way to transition content from the book to the archive. It also focuses on the notebook solely as a product – and the most interesting thing Jack talked to me about was not the notebook as a product, but the notebook as a service.

A service built around permanence

One other interesting aspect of such a service was the idea of a way to emphasise the permanence of the bookmaking process: specifically, by limiting the number of covers in circulation.

The content of these sketchbooks always belongs to the owner; the archived sections and the online archive likewise. But the covers are the property of the service; as more people use them, the binding process means that the back endpaper will build up with patina and wear, giving the book a character of itself. When you cancel your subscription, you turn in your notebook one last time, and receive only archival content back. A new subscriber will get their sketchbooks bound into those covers, the history of previous owners building up on the rear endpaper. I liked that as a way as emphasising the permanence not only of the binding process, but of books themselves, as Jack himself pointed out: ‘books are the longest-surviving information artefacts we have,’ made out of cloth, and glue, and paper – but mainly glue: ‘glue’s amazing‘.

The idea of a service built around these endless notebooks is a fascinating one. I commented that the big weak link in the chain is having to turn in your notebook to update it; finding ways to make this is swift and painless as possible is going to be very important.

I think that the service makes more sense the more local it becomes: rather than couriering your notebook special delivery to a centralized binding point, why not just turn it in at a local franchise? That helps to stress the value of the contents – you can hand over your notebook yourself, ensuring it doesn’t get lost in transit – and also helps cut out the slowest part of the process, the transport. Local binding services might become like 1-hour photo developing services; a drum scanner, a skilled binder, and a lot of glue are all you need. By building the service around local nodes, it also becomes likely that the service will become more personal, and that’s also critical to overcome the trust boundaries that most creatives will likely have when it comes to letting their notebook out of their site.

Finally, the local aspect of such a service can be brought out in another way: through the paper stock used. Paper is manufactured at local levels and it makes sense to build such services around products from local papermills or suppliers. As long as a representative of the overall service confirms that paper stock is fit for use, it means that regional franchises will all have appropriate regional variance in their final product; another way that history and patina is worked into the shells.

It’s likely such a service might not be cheap, but it’s easy to see how the combination of archival, digital backup, and endless pages might be attractive to a certain kind of creative, especially if the franchise outlets were near enough to their hubs. One in Soho, one in Shoreditch; one in the Mission, one in Amsterdam; as a member of a worldwide subscription service, you’d be able to drop into a franchise wherever you were to refresh your book and backup your work, knowing that you were part of an exclusive club built upon one of the strongest, most resilient forms of data storage in history.

And you’d never run out of pages in your notebook, either.