As an historian, I dig through found evidence of past decades looking for unseen intersections between technology and design. The two were of course close mutual contextualizers during the mid-century Modern era and incredibly, the untapped historical record of this era is rich and multi-layered: Monthly and weekly periodicals recorded events as they unfolded, catching disinformation and hypotheses along with facts, and a tremendous range of imagery that was never captured in books or annuals as part of the designated record of the era.

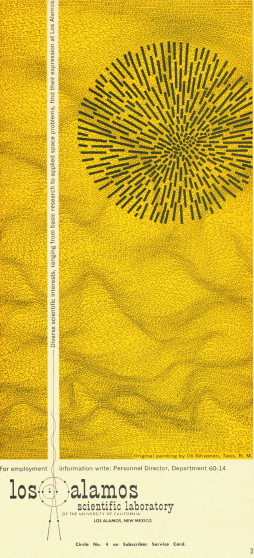

Artwork: Number IX by Oli Sihvonen. Advertisement: LASL in Missiles & Rockets, 1 Feb., 1960

The most compelling imagery is in industrial trade magazine advertising. Aviation Week and Missiles and Rockets of the 1950s and 60s, were both published out of the U.S. during the peak of the Cold War.

Aviation Week, October 1957

Aviation Week has published since the 1940s and is still a world leader in covering military and civilian aerospace technology developments. Missiles and Rockets was a short-lived competitor (1956 – 65), whose pages made up for in style what they lacked in tenure.

Missiles and Rockets, February 1958

Within the realm of monthly and weekly periodicals, trade publications aimed at working professionals within industry are less examined than their internationally-known general interest counterparts such as Science and Scientific American. Together they offer a body of advertising literature that forms a time capsule of the emerging dynamic between design and technology during the late 1950s and very early 1960s, the peak of technological eruption during the Cold War in the U.S. During those years mid-century Modern design asserted itself within the trade-based advertising literature as a powerful visual language with a killer application.

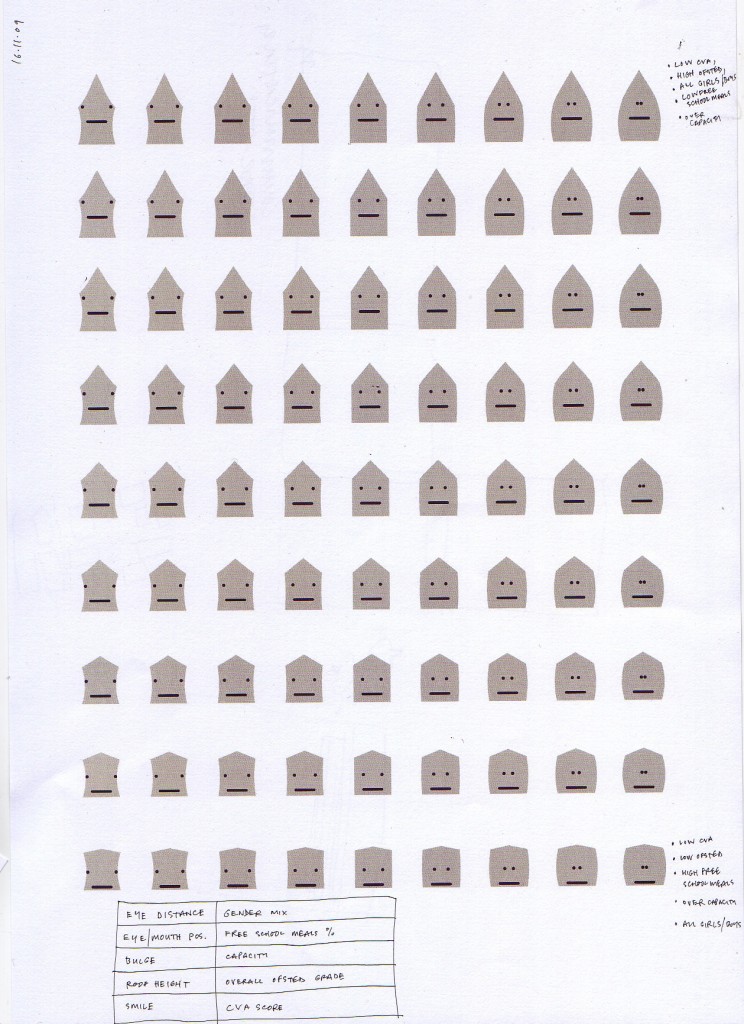

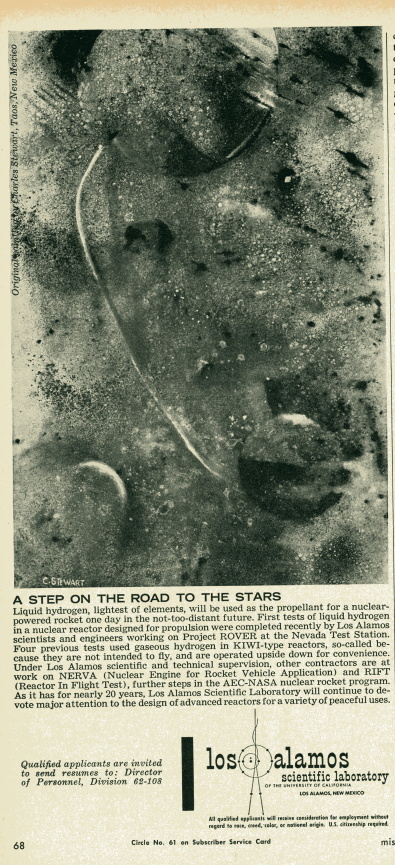

Recruitment advertisements for the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico, illustrate a special case of the relationship between Modernism and industry. This is a set of five images appropriated from regional fine painters into service for the recruitment campaign at Los Alamos.

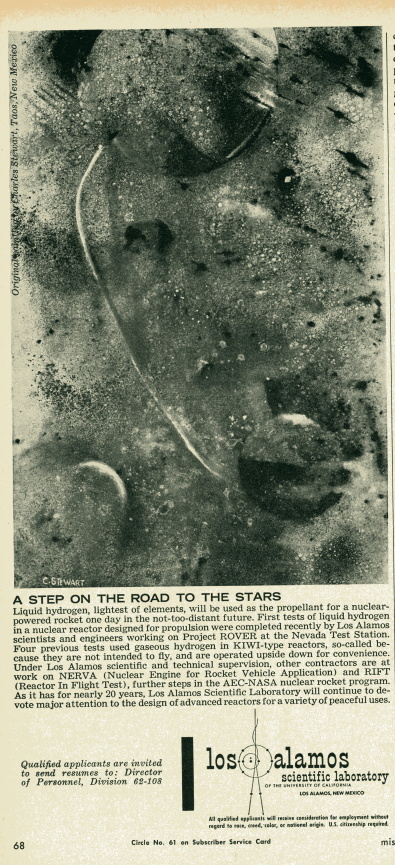

Artwork: Space by Charles Stewart. Advertisement: LASL in Missiles and Rockets, 26 Nov., 1962

The dominant activity of the Laboratory was then, as now, nuclear weapons development. A place seared into public memory by its role as the site of the research and testing of the first atomic bomb, the Laboratory has, since the end of the civil nuclear rocket programs, been mostly a weapons research laboratory. However in the 1950s and 60s there was initiative and federal funding to adapt the atomic legacy to civil purposes. Toward that end Project Rover, sited at the Laboratory, was devoted to the development of a strictly civil-applicable nuclear rocket. The project yielded the NERVA (Nuclear Engine for Rocket Vehicle Application) rocket — mothballed before it was ever tested after political support for it dried up — and the development of small nuclear batteries used in lunar exploration. In those, Laboratory’s program roster included civil space activity as a very large second area of research and development. The dominance of space-related visual motifs in these artworks indicates the widespread prevalence of the civil space program as a leading face of a technological directive that served both martial and peaceful objectives.

Between the two World Wars, a fine arts tradition was established and flourished in nearby Taos, New Mexico, founded by both American and European expatriate artists. Members of this group were thousands of miles from the other early modernist painters, yet their work was in dialogue with the dominant themes of modernism. In New Mexico the movement took shape in the emphasis on a spare, sun-dominated landscape expressed in the works of the Taos artists.

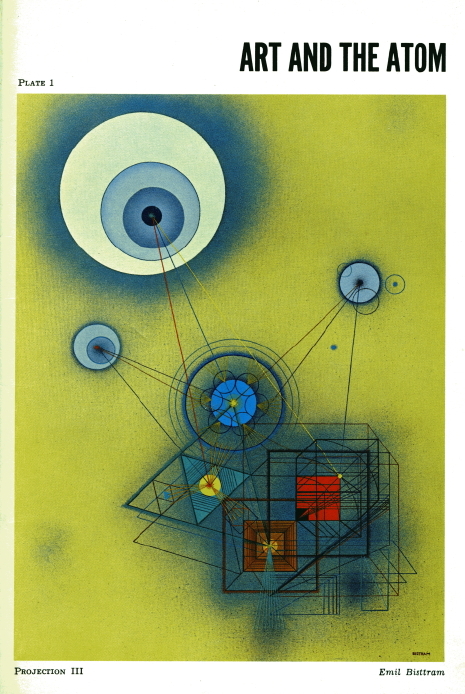

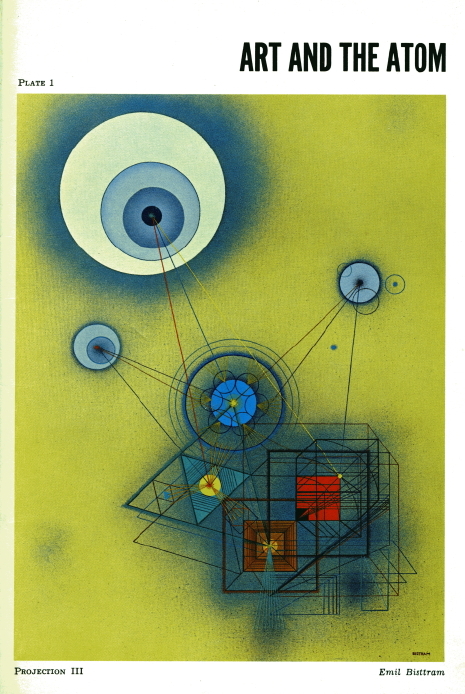

Painter Emil Bisttram started making paintings titled Space Images as early as 1954.1 In his work, the interplanetary and interstellar landscape of space that the enormous New Mexico sky brought into close juxtaposition with the high desert is recast as a suitable subject for depiction in an abstract expressionist mode. Bisttram’s Ascending, has been subtitled by the Laboratory: “scientific objectivity characterizes the examination of natural forces in the experimental laboratories at Los Alamos.”2 In the painting, Bisttram combines an abstraction of space with a strong suggestion of the mechanical engineering processes that will get us there:

Artwork: Ascending by Emil Bisttram, 1958. Advertisement: LASL in Missiles and Rockets, 6 June, 1960

The form that dominates the center right of the painting, and the lines that attach all the forms to one another, are suggestive of engineering diagrams. Or even internal rocket structure, or just the process of forming connection between one idea and the next. One possible extrapolation, that the abstracted systems/bodies at the top, bottom, and left center of the image represent planets and orbits, is left to the viewer’s imagination.

The geographic relationship between the LASL research station and the landscape that inspired the Taos artists led to a neighborly connection between the two that adds considerable depth to the relationship between the images and their “subject matter.” Incredibly, a catalog prepared for an exhibition of the works, titled Art and the Atom, explains that the works were not commissioned for the advertisements. Instead advertisements were created by Laboratory personnel director Robert Meier based on pre-existing artworks. In other words, the “profound dialogic relationship with environment”3 that inspired the artists was an independent parallel to the functionally dialogic relationship with the environment held by the LASL nuclear test facility. These parallel lines of development are expressed poetically in Art and the Atom:

“The artist is aware of space, mass, motion and energy. He is cognizant of our world in conjunction with outer space and is abreast of the development in the world of science. He searches intuitively rather than theoretically. The scientist is equally involved with the same observations. He explores the potentials; he is the discoverer: the man of research. Both artist and scientist are involved with the mysteries of the Universe.”

—Leone Kahl, Director, Stables Art Gallery, Taos, ca. 19634

Exhibition catalog, pub. The Stables Art Gallery of Taos. n.d., circa 1963.

In the foreword to Art and the Atom, Reginald Fisher, then director of the El Paso Museum of Art, writes that “the semantics of this exhibition revolve around such terms as: space, energy, motion, dynamics, thrust, propulsion, acceleration, curiosity, probe, experiment, empirical, technology, mystery, experience.” He notes that the paintings were selected from pre-existing artworks “on the basis of the capacity of the particular piece to portray symbolically the essence of the research field under consideration [for recruitment].” The remaining historical evidence of this transaction between industry and artist is mute on the question of how the artists felt having their works utilized in this manner, or whether any chose to opt out.

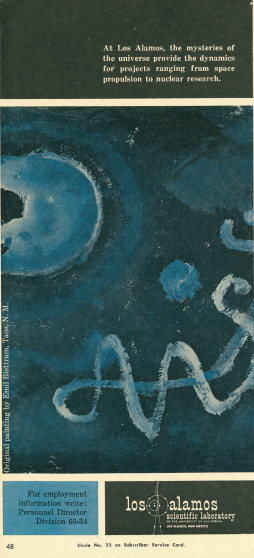

Below is a straightforward meditation by Bisttram on the shapes and spaces that emerge when a painter contemplates a starscape. The inky midnight blue shades here echo the tones used by Van Gogh in his Starry Night, but here space is foregrounded through the omission of a ground plane. The figure–ground shift in this image has captured what the Earth-centric regulatory approach to space neglects to account for: that in space there is no “ground,” only the whole new spatial logic of the solar system environment. Titled Moon Magic by the artist, its catalog description carries the added thought, “Mysteries of the universe provide the dynamics for projects.”

Artwork: Moon Magic by Emil Bisttram, 1958. Advertisement: LASL in Missiles and Rockets, 25 April, 1960

Taos artist Oli Sihvonen extends the visual language connecting atomics research and space themes to the regional landscape. In the top image (far above), a background field that could be sand, desert, or stylized space billows behind a round shape that suggests the sun, or of course, the atom, or perhaps is meant to suggest both at the same time. The work is titled Number IX, and in the catalog bears the subtitle “Diverse scientific interests ranging from basic research to space problems.” The organic shape of the rippled background suggests the desert, a natural environment. The image takes a step toward minimalism in its reduction of the field to its two dominant shapes, the golden rectangular ground and the spherical black figure of the “sun.”

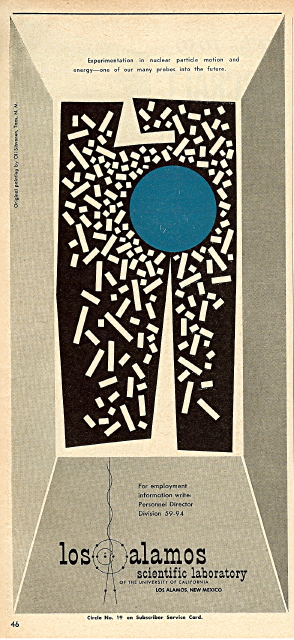

The work below by Sihvonen is titled Blue Spot, subtitled “Experimentation in nuclear motion and energy:”

Artwork: Blue Spot by Oli Sihvonen. Advertisement: LASL in Missiles and Rockets, 5 October 1959

The blue spot disrupts the conventionally romantic stylization of planetary or solar bodies by contracting the sphere to its minimal form. Sihvonen here seems to references the early 20th century Russian constructivists, with the prolonged vertical angular shape aimed at the planetary circle. It brings to mind El Lissitzsky’s constructivist graphic composition Beat Back the Whites with the Red Wedge which pioneered the use of juxtaposed triangle and circle as a graphic strategy to represent political conflict. I find it ironic that the graphic legacy of Communist action should be re-articulated and put into service — whether with or without the artists’ sanction — in the service of American Cold War-era weapons and civil space technological programming.

The investigation that yielded the discovery of these artworks and their history is part of a larger project: In Spring 2010 Blast Books will publish my monograph Another Science Fiction: Advertising the Space Race 1957–62, which gathers and interprets over 175 advertising images from Aviation Week and Missiles and Rockets. It clusters the advertisements into five subjects, including those that recruit for satellites, for human space exploration, for propulsion systems engineering, and for projects that recast space as a new landscape. Lastly, Mid-Century Modern Space rounds out the book with a longer discussion of industry’s use of modern design in advertising. This essay was adapted from this chapter.

The book itself is but one product of the cultural enterprise co-developed by my spouse Rick and myself: The Prelinger Library (http://www.prelingerlibrary.org), a private research library that is open to the public in San Francisco. We are an experimental, image-appropriation friendly library with both analog and digital holdings, including over 30,000 titles and ephemeral artefacts in the areas of media, technology, and landscape and social history. Thanks to BERG for visiting us this past summer! All are invited.