So where did all this work end up? Metal Phone is a project that comprises a mobile and a machine, and talks to all the strands we’ve been investigating: personalisation, manufacture, materials and so on. Read on for a discussion of the themes and lots of pictures.

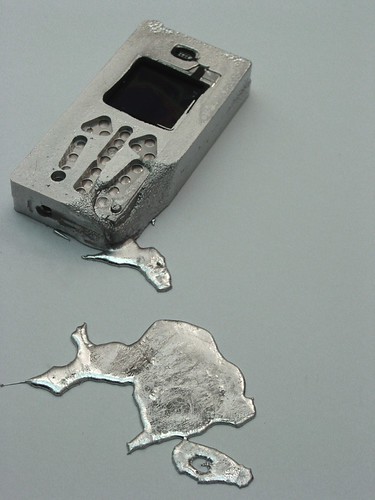

Briefly, we’ve been using a low-melting point alloy that allows us to cast and recast a mobile phone shell using only hot air or water. It’s a remarkable piece to hold in your hand, mainly because it looks like a regular phone as if it were made by the ancient Egyptians, or found on the sea floor. (It’s also really heavy because it’s mostly lead.)

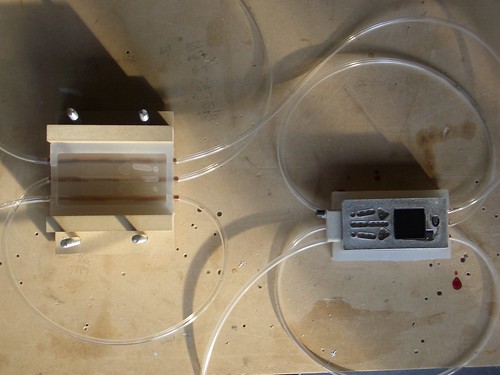

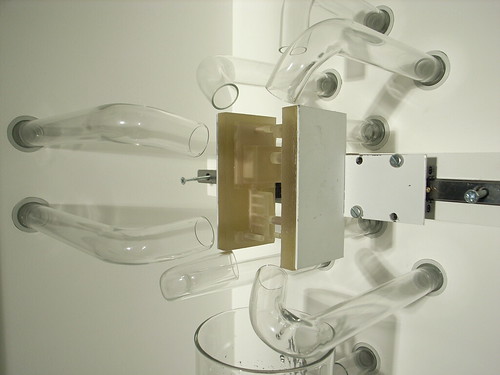

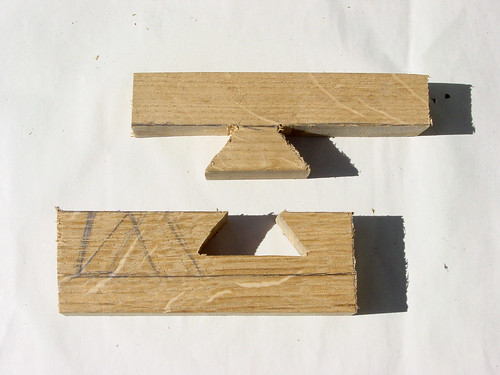

The ease of this manufacture means that we get to discuss the local factory angle of personalisation. That is, could purchasing a mobile phone be more like a performance of manufacture? Could it be more like a vending experience? To this end, Metal Phone comes with a machine that melts and reforms a phone around the internals of a standard Nokia handset (the 5140i).

Jack has been working a lot on this project over the past couple of months and he’s currently showing it at the Royal College of Art’s Summer Show 2006 in London (on till 2 July, if you want to see it).

There’s a lot more to say about this project, and also the other investigations we’ve commissioned that took us to this point, but for the moment I just wanted to post the text from the leaflet that goes with the project, and show you some photos.

For members of the press, print-quality photos of everything you see here are available if you mail us at info@berglondon.com.

INTRODUCTION

Metal Phone is a mobile phone within limits. You’ll need strong pockets. The metal reduces the effectiveness of the aerial so you’ll need to be closer to the transmitter. If you leave your mobile on the dashboard of your car on a hot day, you’ll come back to find the components in a pool of liquid metal. It’s not advisable to hold the phone in your hands for too long—cadmium is present in a low concentration.

FLUIDITY

The Nokia 5140i is an illusory object. Disconnected from the network when you’re underground, it becomes a lump of plastics and metals. Although safe in your hands, you wouldn’t want to eat the components. It, too, would lose its shape in an oven—in time, it would break apart anyway.

The appearance of solid edges to this phone—in time, space, and the market-place—is maintained at great effort. The Nokia is a brief confluence in the flows of all these materials, held in place by utilising glues, factories, the entire knowledge of the behaviour of plastics; college degrees and health and safety and the insistence marketing has on a handset (rather than separate pieces) in the first instance.

The mobile phone acts as a thing because material science and market forces make it a thing. Consumer electronics do not drop into the world formed like rocks and trees. They exist because of human endeavour.

RECHANNELLING

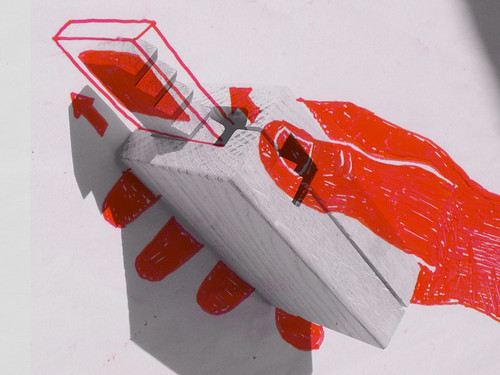

If this endeavour was rechannelled, could the Metal Phone be other things? Could its natural fluidity be sped up and used in the co-design of the object, instead of being locked out of the production line?

EXPECTATIONS

In the hand, Metal Phone asks questions of our expectations of mobile phones, pushed by its aesthetic and material qualities. The weight and seemingly permanent form is set against the ephemeral nature of the alloy housing. Of course Metal Phone isn’t permanent—it also explores personalisation in mobile phone products. The project looks at people’s ability to alter and choose the form of their phones and what affects this, as much as the effect the static form has on their beliefs and ideas around those objects.

PERMANENCE INVERSION

Though fluid, Metal Phone offers a new kind of permanence: it offers relief from sculpted plastic forms yet makes no attempt to accommodate interface by changing the surface shape. The shape is no longer defined by constraints such as manufacturing cost or the fashion in electronics. A consumer may upgrade the interior and the screen interface a dozen times, but keep the weight and form of the shell the same for a decade.

CONSUMER MACHINE

Metal Phone seeks to undermine the current experience of choosing a plastic replica fastened by a security tag to the wall of a handset outlet. The machine represents a vending model for fabrication of the phone in-store, extending the production line to the buyer’s palm. Metal Phone proposes an experience in which consumers witness and participate in the fabrication of their products through novel techniques at the point-of-sale and subsequently.

FUTURE

Schulze & Webb are continuing their work with Metal Phone and are developing a more consumable range of transformable products. Metal Phone is an extension of work for Chris Heathcote of Nokia, Insight Foresight Group (now NEXT) to develop prototypes exploring personalisation in mobile phones.