Mercury

In 2057, the Sun is dying, and the Earth is freezing. So the ship Icarus 2 goes on a mission to reignite it with a massive bomb. This is the movie Sunshine, and if you get a chance to see it, watch it on a big screen. The crew themselves watch the Sun close-up, awestruck, from a view-port the exact dimensions of a movie screen, so the Sun fills your picture too and you spend half the film bathing in powerful yellow light. Like some kind of church.

On the way, they slingshot past – and watch – Mercury, and this sequence is accompanied by one of the best tracks on the remarkable soundtrack (Paul Murphy/Underworld).

Venus

Earth is crazy over-populated and an effort to colonise Venus has begun. But nobody wants to go, because Venus is a terrible place to live. The Space Merchants (Frederik Pohl and C. M. Kornbluth) is about an executive at the advertising agency with the account to sell Venus as an idea.

This is against the back-drop of a world gone totally consumerist. A terrorist organisation named ‘the Consies’ fights against the status quo. I wrote about this on my personal blog in 2007.

Earth

Most people die in some kind of unknown pandemic. Ish Williams lives, and Earth Abides (George Stewart) tells of the next 80 years, from the scrabble to survive, the re-use of the useless artefacts of civilisation, and the early days of fragile rebuilding. The story goes into great detail, and is utterly convincing. In the third section, our main character is elderly and frail, and the narrative comes at you as a patchy, foggy lucidity, as is as excellent a meditation on old age as I’ve read anywhere, sci-fi or otherwise.

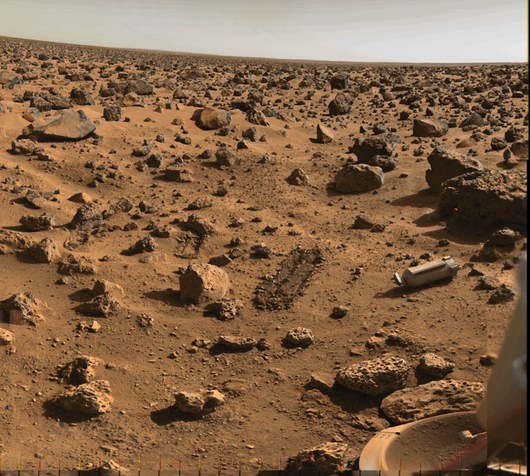

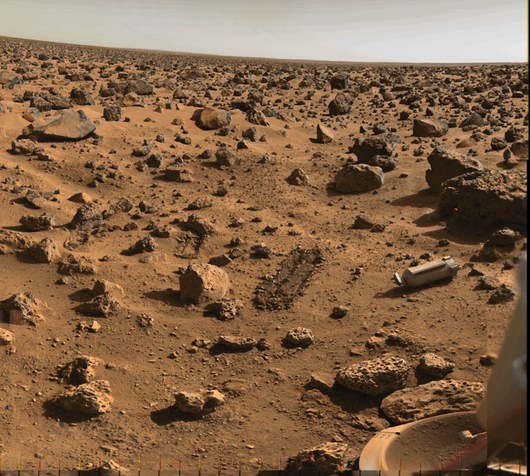

Mars

The first words on Mars are spoken by John Boone: “Well, here we are.” He later joins the First Hundred, the groups that colonises Mars in 2026. Over the following decades, terraforming begins, other colonists arrive, John travels, and cities are built. In 2056, he makes a speech at Nicosia, a new city, and is murdered.

Kim Stanley Robinson’s trilogy Red Mars, Green Mars, Blue Mars tells the story of 200 years of future history. It is a trilogy about friendships, science and nature and people and the social negotiation between and of all of them, terraforming, politics and constitutions, space elevators, and the solar system.

Jupiter

Jupiter is the destination of the spaceship Discovery in the film 2001: A Space Odyssey. I fell in love at a young age with the infinity of Jupiter and the artificial intelligence, HAL. Stanley Kubrick spoke about HAL in this 1969 interview:

One of the things we were trying to convey in this part of the film is the reality of a world populated — as ours soon will be — by machine entities who have as much, or more, intelligence as human beings, and who have the same emotional potentialities in their personalities as human beings. We wanted to stimulate people to think what it would be like to share a planet with such creatures.

(Kubrick interview via kottke.)

Jupiter also features in Ken Macleod’s books. I’ll repeat what I said in week 279:

There’s a bit in Ken Macleod’s sci-fi quartet, the Fall Revolution series, where Dave Reid’s company “Mutual Protection” are in orbit around Jupiter, building a massive, complex structure to instantiate a wormhole to the edge of the universe. It takes several years. To build it they have whole populations of uploaded human consciousnesses that occupy and run construction robots (uploaded minds are easier than writing artificial intelligences). They call these robot clusters macros.

Saturn

Before the planets formed, the solar system was the accretion disc, a vast spinning disc of trillions of asteroids and planetoids. Here lived the space spiders, and I’ll quote from the book:

On plains of web as broad as continents, palaces of silken thread arose. On silken parachutes the spiders’ young went soaring outwards on the solar wind to colonise clumps of lonely stone still further from the Sun. Spider musicians stretched harps of web across the sky, and filled the aether with their music. Spider artists caught sunlight in great discs of web, and broke it into rainbows.

Beautiful. That was a billion years ago. Now the spiders live in a much reduced accretion disc: Saturn’s rings. Philip Reeve’s book is sci-fi meets steampunk meets Victorian adventure yarn: Larklight.

Uranus

There’s not much that springs to mind for me about Uranus, other than it moves around the Sun by rolling, like a ball, rather than spinning like all the other planets.

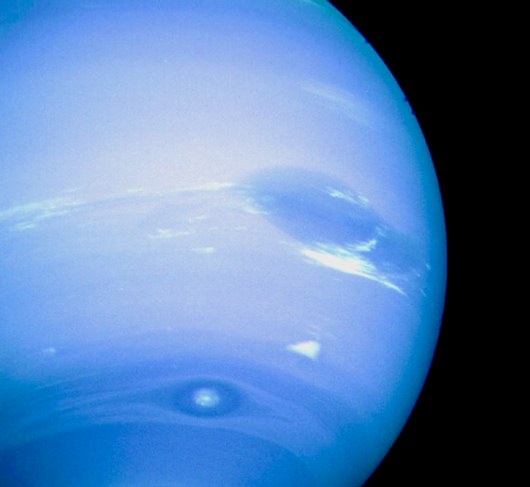

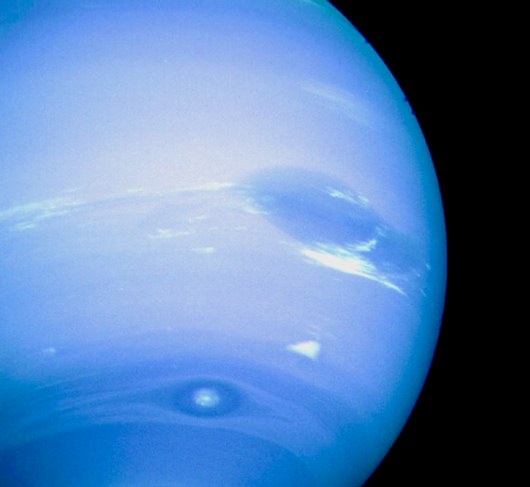

Neptune

In 2 billion years, Neptune is the home of the 18th species of humankind. Humanity’s history has been one of alternating triumph and tragic almost-extinction (Last and First Men, Olaf Stapledon.) Each species is human in a different way: with music at their heart, or artificial giant brains, or born to live in the air, or squat like crabs.

The 18th human has dozens of sexes, six legs, and an eye in the top of its head which – when they link together in planetwide telepathic communion – lets them see far into space like a single large area telescope.

Also Neptune is my favourite colour blue, and it has all kind of magical resonances for me which you can read about in the final slides of my presentation, Escalante.

The talk ends like this:

Blue is a good colour. It’s the colour of Neptune, of course; it’s the colour of the future of humanity. It is the colour of deep seas and of Cherenkov radiation. When we finally move on from Earth in the late 24th century and take over the solar system, our city-sized generation ships will take off into clear blue skies just like this.

And so on.

(Here are two previous talks of mine about sci-fi: Sci-fi I like (2006); and A science fictional tour of the solar system (2008).)