The above is a post-it note, which as I recall is from a workshop at IDEO Palo Alto I attended while I was at Nokia.

And, as I recall, it was probably either Charlie Schick or Charles Warren who scribbled this down and stuck it on the wall as I was talking about what was a recurring theme for me back then.

Recently I’ve been thinking about it again.

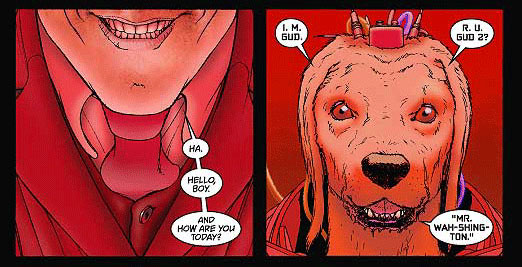

B.A.S.A.A.P. is short for Be As Smart As A Puppy, which is my short-hand for a bunch of things I’ve been thinking about… Ooh… Since 2002 or so I think, and a conversation in a california car-park with Matt Webb.

It was my term for a bunch of things that encompass some 3rd rail issues for UI designers like proactive personalisation and interaction, examined in the work of Byron and Nass, exemplified by (and forever-after-vilified-as) Microsoft’s Bob and Clippy (RIP). A bunch of things about bots and daemons, conversational interface.

And lately, a bunch of things about machine learning – and for want of a better term, consumer-grade artificial intelligence.

BASAAP is my way of thinking about avoiding the ‘uncanny valley‘ in such things.

Making smart things that don’t try to be too smart and fail, and indeed, by design, make endearing failures in their attempts to learn and improve. Like puppies.

Cut forward a few years.

At Dopplr, Tom Insam and Matt B. used to astonish me with links and chat about where the leading-edge of hackable, commonly-employable machine learning was heading.

Startups like songkick and last.fm amongst others were full of smart cookies making use of machine learning, data-mining and a bunch of other techniques I’m not smart enough to remember (let-alone reference), to create reactive, anticipatory systems from large amounts of data in a certain domain.

Now, machine-learning is superhot.

The web has become a web-of-data, data-mining technology is becoming a common component of services, and processing power on tap in the cloud means that experimentation is cheap. The amount of data available makes things possible that were impossible a few years ago.

I was chatting with Matt B. again this weekend about writing this post, and he told me that the algorithms involved are old. It’s just that the data and the processing power is there now to actually get to results. Google’s Peter Norvig has been quoted as saying “All models are wrong, and increasingly you can succeed without them.“.

Things like Hunch are making an impression in the mainstream. Google Priority Inbox, launched recently, make the utility of such approaches clear.

BASAAP services are here.

BASAAP things are on the horizon.

As Mike Kuniavsky has pointed out – we are past the point of “Peak Mhz”:

driving ubiquitous computing, as their chips become more efficient, smaller and cheaper, thus making them increasingly easier to include into everyday objects.

This is ApriPoco by Toshiba. It’s a household robot.

It works by picking up signals from standard remote controls and asks you what you are doing, to which you are supposed to reply in a clear voice. Eventually it will know how to turn on your television, switch to a specific channel, or play a DVD simply by being told. This system solves the problem that conventional speech recognition technology has with some accents or words, since it is trained by each individual user. It can send signals from IR transmitters in its arms, and has cameras in its head with which it can identify specific users.

Not perhaps the most pressing need that you have in your house, but interesting none-the-less.

Imagine this not as a device, but as an actor in your home.

The face-recognition is particularly interesting.

My £100 camera has a ‘smile-detection’ mode, which is becoming common. It can also recognise more faces that a 6-month old human child. Imagine this then, mixed with ApriPoco, registering and remembering smiles and laughter.

Go further, plug it into the internet. Into big data.

As Tom suggested on our studio mailing list: recognising background chatter of people not paying attention. Plugged into something like Shownar, constantly updating the data of what people are paying attention to, and feeding back suggestions of surprising and interesting things to watch.

Imagine a household of hunchbots.

Each of them working across a little domain within your home. Each building up tiny caches of emotional intelligence about you, cross-referencing them with machine learning across big data from the internet. They would make small choices autonomously around you, for you, with you – and do it well. Surprisingly well. Endearingly well.

They would be as smart as puppies.

Hunch-Puppies…?

Ahem.

Of course, there’s the other side of domesticated intelligences.

Matt W.’s been tracking the bleed of AI into the Argos catalogue, particularly the toy pages for some time.

The above photo of toys from Argos he took was given the title: “They do their little swarming thing and have these incredibly obscure interactions”

That might be part of the near-future: being surrounded by things that are helping us, that we struggle to build a model of how they are doing it in our minds. That we can’t directly map to our own behaviour. A demon-haunted world. This is not so far from most people’s experience of computers (and we’re back to Byron and Nass) but we’re talking about things that change their behaviour based on their environment and their interactions with us, and that have a certain mobility and agency in our world.

I’m reminded of the work of Rodney Brooks and the BEAM approach to robotics, although hopefully more AIBO than Runaways.

Again, staying on the puppy side of the uncanny valley is a design strategy here – as is the guidance within Adam Greenfield’s “Everyware”: how to think of design for ubiquitous systems that behave as sensing, learning actors in contexts beyond the screen.

Adam’s book is written as a series of theses (to be nailed to the door of a corporation or two?), and thinking of his “Thesis #37″ in connection with BASAAP intelligences in the home of the near-future amuses me in this context:

“Everyday life presents designers of everyware with a particularly difficult case because so very much about it is tacit, unspoken, or defined with insufficient precision.”

This cuts both ways in a near-future world of domesticated intelligences, and that might be no bad thing. Think of the intuitions and patterns – the state machine – your pets build up of you, and vice-versa. You don’t understand pets as tools, even if they perform ‘job-like’ roles. They don’t really know what we are.

We’ll never really understand what we look like from the other side of the Uncanny Valley.

What is this going to feel like?

Non-human actors in our home, that we’ve selected personally and culturally. Designed and constructed but not finished. Learning and bonding. That intelligence can look as alien as staring into the eye of a bird (ever done that? Brrr.) or as warm as looking into the face of a puppy. New nature.

What is that going to feel like?

We’ll know very soon.

Another open-source product making its debut in hardware is the OpenOffice.org Mouse (pictured left). Eighteen buttons, an analogue joystick… I admit to sucking my teeth in disbelief when I first saw it; the comparisons that have been made to

Another open-source product making its debut in hardware is the OpenOffice.org Mouse (pictured left). Eighteen buttons, an analogue joystick… I admit to sucking my teeth in disbelief when I first saw it; the comparisons that have been made to