Investigating the future of food - specifically the implications of meat grown in labs rather than harvested from living creatures, in terms of systems, products, and culture.

While at the RCA, Jack took part in a brief run by Tony Dunne on the industrial future of food and lab-grown meat (a staple of the newspaper columns in 2005). This presentation comes from a two week exploration that also involved the making of replica origami food, as shown in the slides.

From Dunne’s original brief: “Scientists are developing methods of growing meat in labs using animal cells. This area of research, called In Vitro-Cultured Meat Production raises all sorts of complex issues about the meaning of food, our relationship to animals (and nature), human values and behaviours, and even taboos. […] The purpose of the project is to explore how design can be used as a medium to draw attention to the social, cultural and ethical implications of ‘cultured meat’.”

Jack’s images and notes follow (original images are owned by S&W; please get in touch if you’d like to republish them):

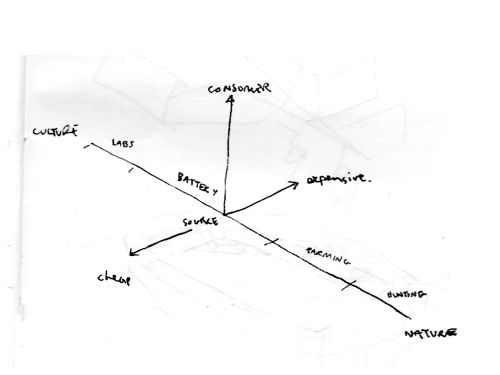

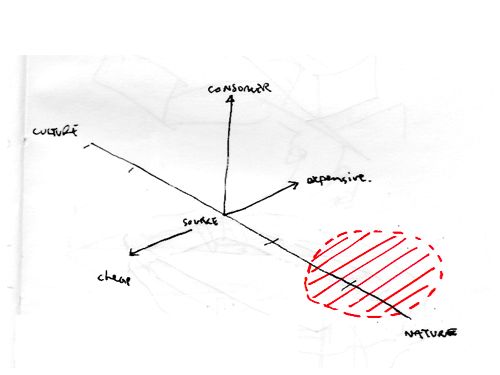

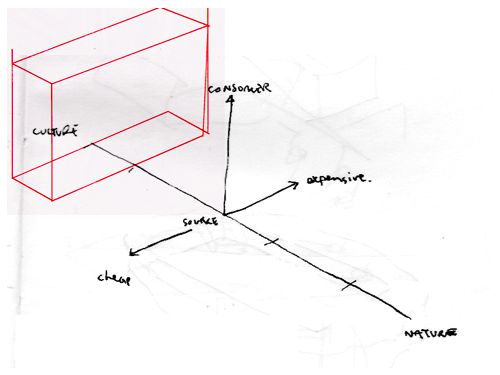

This is a map of how we perceive the food we consume and I’ve mapped it on three axes:

- between cheap and expensive

- between things that are very cultivated and artificial, and things that are very natural

- at the bottom is food at the point where it’s made; the top is the point at which it’s consumed

It’s about how we perceive food rather than how it actually is.

At the very cultivated end we’ve got laboratories and battery farms. Then farms and then hunting, which is maybe closest to the natural end.

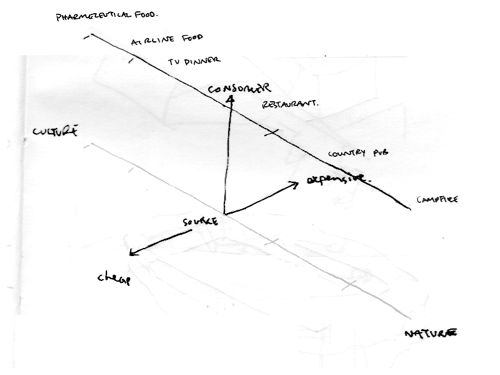

At the top here, at the point at which food is consumed, at the very back there’s pharmaceutical pills, then airline food and TV dinners.

We go through to restaurants and country pubs—maybe there’s a geographical thing about being closer to nature. And finally campfires where you’re cooking the food yourself, sitting with nature surrounding you.

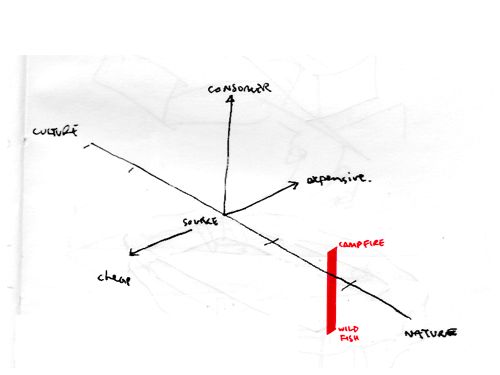

Certain foods have a linear path through consumption. Wild fish cost nothing to catch—or at least in our perception they’re very cheap (but you’d probably have to pay to be allowed to fish). Then you cook them on your campfire. That’s very natural, and very cheap too.

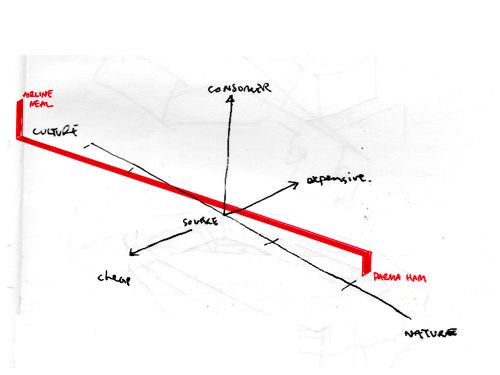

And certain foods have a very skewed path from production to consumption. Parma ham for example: It’s perceived to be very natural and also quite expensive—hand-made, oak-smoked. And then somehow on the way to you it ends up in an airline meal which is really cheap and extremely cultivated.

The area I think most of us aspire to eat in, is expensive, natural food. This is organic food, local food and the like.

The area I’m interested in exploring is up here in extremely cultivated food. Food made in a laboratory maybe.

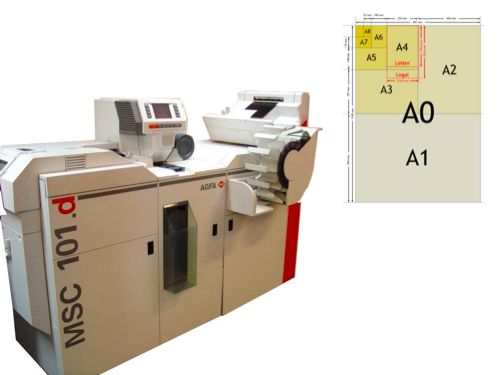

One of the only known truths about laboratory-grown meat—the only real thing we know about it at the moment—is that the meat has to be very thin for the oxygen to get to it. If it weren’t thin, you’d need to grow blood vessels and that would make it a much more complicated exercise.

It’s wet and very flat.

Now in the way new technologies emerge and change markets, often it’s companies that have something quite strange and simple in common with the technology that do well. It’s a bit like the way wire manufacturers started making fibre optic cables, just because they were good at extruding miles of stuff—even though there doesn’t seem to be any other relationship between the two technologies apart from their physical similarity.

In this case I’ve started to look at photo processing labs as systems that deal with wet, flat material. They include wet paper, and highly engineered processes.

My contention is that AGFA or some photo processing company would start producing lab-grown meat machines.

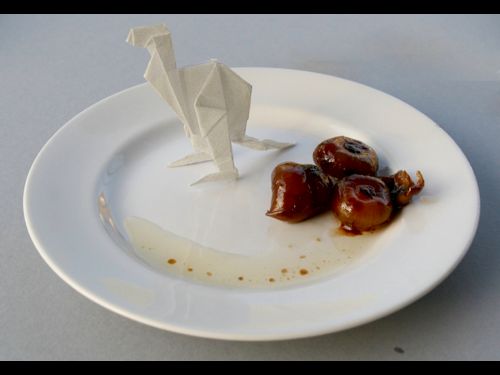

This work talks about how the lab-grown meat transition will affect the public-facing processes of food and its consumption, and also how it will affect craft and expertise in the world of food.

Much of the practices and language around cooking seems to have come from the materiality of food, and a sensitivity towards its condition and how it will behave as it is cooked. Minor mistakes in cooking or insensitivity to the material can ruin meals.

Lab-grown meat, in the context of cooking, will need to find and cut out new paths for itself, new areas of expertise, and new tools and practices associated with its own physical nature and how it behaves. Restaurant culture and the performative nature of chef expertise (to flambé for example) will need to be re-established in different forms.

I propose that initially, skills in parallel areas will be borrowed to lend weight to these practices so that the industrial and artificial nature of the meat can be celebrated.

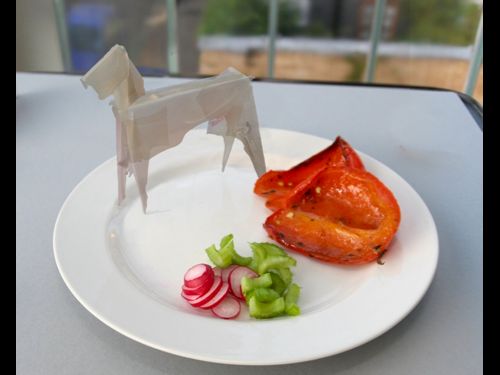

We can look at origami as a very careful and highly developed skill, as a way of restoring some integrity to the craft of food preparation in an expert context.

The above, for example is a kangaroo steak with some pickled onions.

And this is a bull mastiff steak with some peppers and some radishes.

There’s got to be some way to communicate the nature of the meat. With food now, steak looks like steak. Chicken legs look like chickens’ legs.

How do we represent the history or memory of the animal? Origami plays a role in that too.

These are some images I put together to think about how growing meat in a lab, and the opportunity that gives us, might change the way we see and look at food. This person is eating ostrich.

I think this one in particular is important. This chap on the left is having a greyhound steak. Since no animal died to produce the meat, it would be possible to eat meat that would otherwise have been ethically unthinkable. The idea of the British eating dogs in pubs is unlikely, but here… well.

The other thing is that we could end up with some quite novelty products.

The chap on the right probably thought it was quite funny to order a Pink Panther steak, but now he’s got it and he’s got to eat it, he rather wishes he’d had something sensible instead.

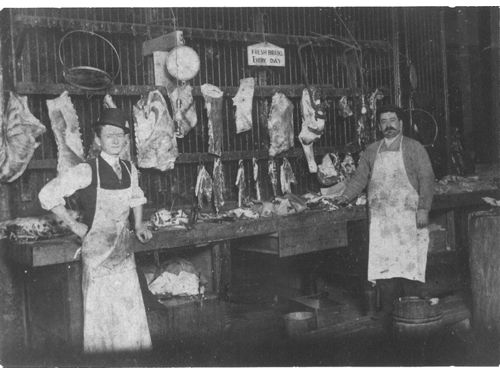

I was also thinking about the craft of butchery, and what lab meat would mean to the whole territory of the way butchers—as people—work.

It’s very much in the way that people expert in Letterpress had to change in the past. Their industry has almost disappeared, and now although it’s still extremely beautiful and very skilled, it’s been relegated to a relatively small number of people, for customers who want this novel design trait and students as part of their education in art schools. Little Letterpress exists outside these areas in working practice today.

Butchers would have to go the same way.

Really there aren’t many butchers left even now. The average age is high. In another ten years there may not be many left.

With lab meat, butchers would have to start working with the equipment in front of them, just like Letterpress people have had to shift to work with Epson and digital print types.

This image shows a very bloodless butcher—there’s no mess any more.

There are all the trappings of the butcher, like the red striped apron and the clean counter and the glass front and the scales. They’re almost superfluous because here you probably buy your meat by the A-size, like paper. Instead of a particular steak or a particular cut, you get an A0 (poster size) bull mastiff steak, or a 16-by-9 kangaroo steak.

There’s a loss of craft, and a sense that the butcher has been reduced to a side-show. The skills the butcher had are now only really important as part of the aesthetic, or in selling the meat, or in retaining some of its historical context, or integrity.

The future of food

The second provocation, the butcher, explores how radical technological changes in food changes affect our patterns of living and expectations of what we consume. It presents a dystopian vision of craft and how our perception and consumption of food will change.

Industrialised food already works hard to preserve what remnants of nature it can cling to. Chicken restaurants reconstitute chicken to make it seem less artificial.

The origami, the first provocation, seeks to explore how industries or practices might shift to not merely accommodate but indulge, celebrate and build upon the artifice in food. It wants to allow those processes to define and create new patterns for how we eat, tapping into an affection for novelty and performance (who could have imagined 15 years ago we would be eating raw fish off a conveyor belt?)

—Jack.